Voting Rights Stop at the Workplace Doors

The labor battle at Amazon’s warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, displayed once again how easily democratic norms get tossed out in union elections.

Luis Feliz Leon | April 25, 2022

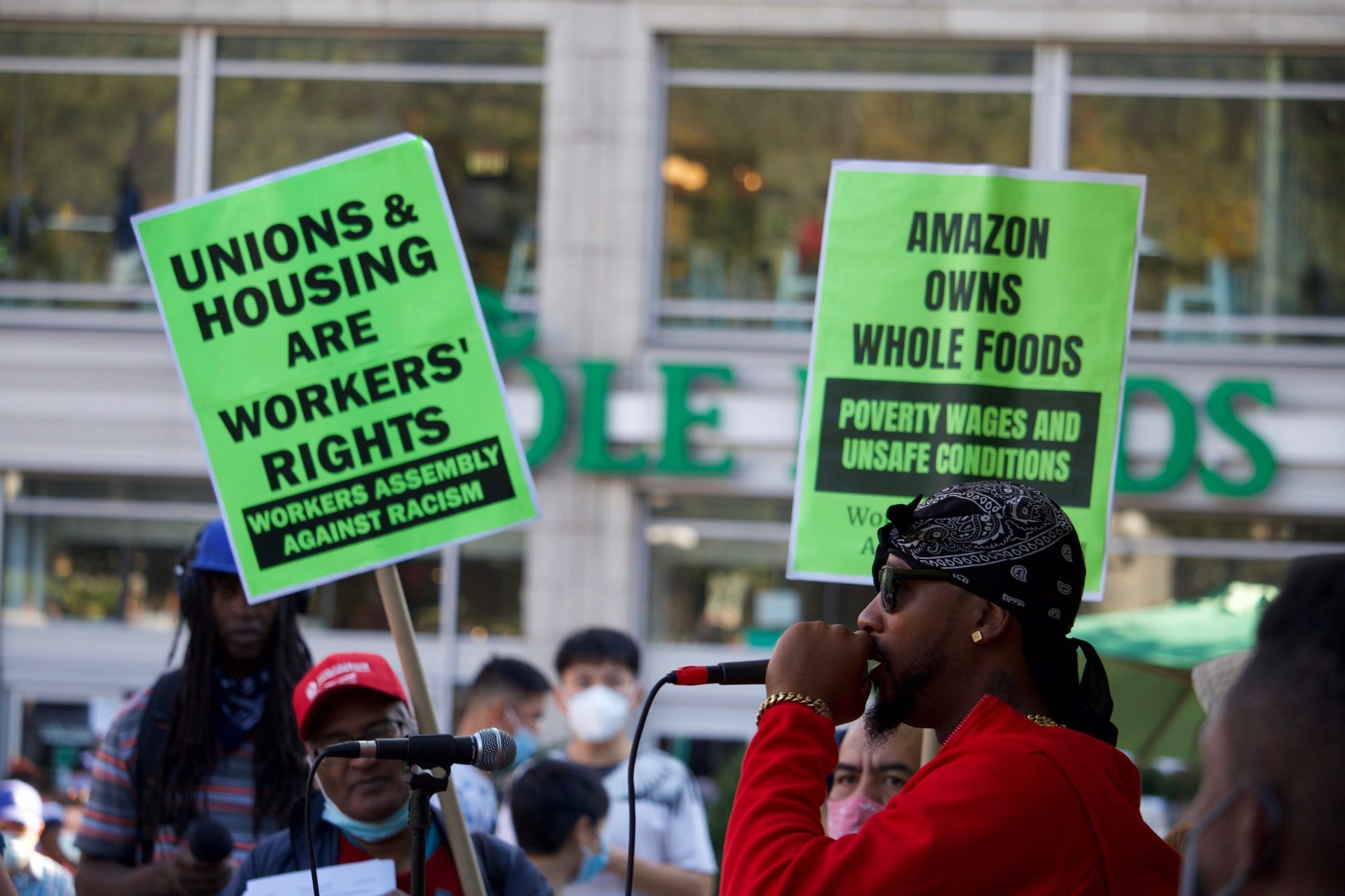

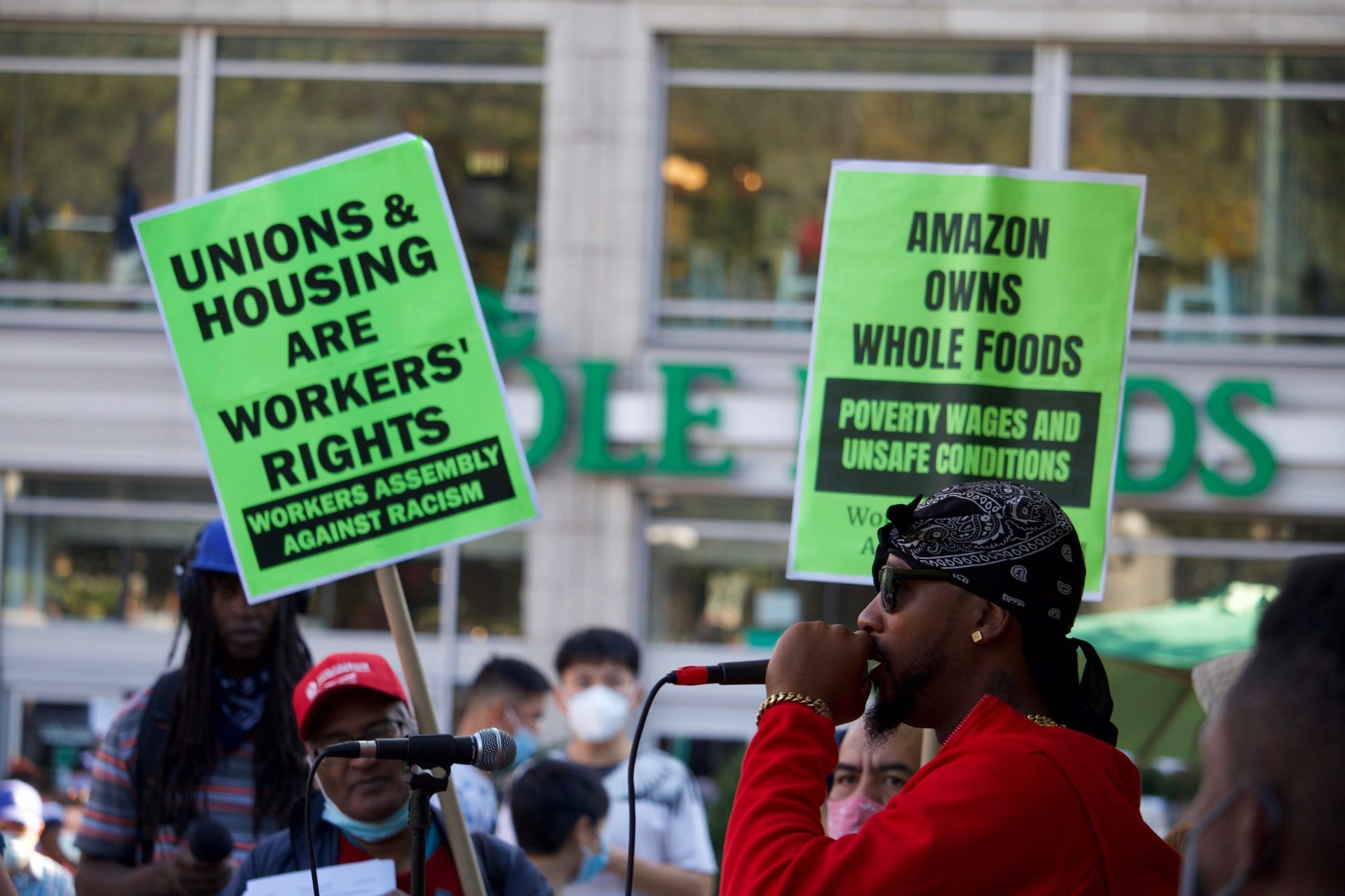

In early April, as workers clinched a stunning union victory at the Amazon warehouse JFK8 on Staten Island in New York City, workers at another Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama appeared to narrowly reject forming a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU).

The results remain uncertain since the union and Amazon have contested 416 ballots, which is more than three times the margin. But the RWDSU has also asked the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to set aside the election because of Amazon’s flagrantly illegal conduct, saying the company retaliated against pro-union workers and “created an atmosphere of confusion, coercion and/or fear of reprisals and thus interfered with the employees’ freedom of choice.”

This election was already a redo of a vote that took place in 2021, when Amazon faced similar complaints. It plastered bathroom stalls with anti-union propaganda, paid consultants to spread anti-union messages on the warehouse floor, and forced workers to sit through mandatory sessions that badmouthed the union known as “captive audience” meetings.

Amazon also fought the use of mail ballots during height of the pandemic due to the “party fraud and coercion that is characteristic of mail-ballot elections,” mirroring former President Donald Trump’s false claims that absentee voting opens the door to widespread voter fraud just months after the 2020 presidential election. After it lost its effort to ban mail ballots, it installed a mailbox to deposit ballots on the warehouse grounds in view of surveillance cameras, and even got the timing of nearby traffic lights changed to make it harder for union organizers to approach workers in their cars.

RWDSU President Stuart Appelbaum wonders how people would respond if an election for public office was conducted the way unionization elections are run, with democratic norms thrown out the window.

“Imagine if we did this in political elections,” he told Bolts. “You hold the election in one candidate’s headquarters. You force people to vote at these meetings for one candidate, and the facility is plastered with the propaganda of just one candidate. Nobody would think that was a fair election process.”

There is renewed interest for voting rights in progressive circles today, spurring momentum for strengthening access to the ballot in Democratic-run states. But that energy has largely stopped at the doors of the workplace. Labor organizers must confront a playing field with little fairness and a general indifference toward respecting democratic procedures, let alone giving workers more direct control.

In union elections, democratic norms—from the basic standards of free and open elections to free speech protections—are routinely cast aside. Many tactics that violate them are legal, and when companies breach labor law they are often only asked to post a notice with the promise to forswear lawbreaking in the future.

Gordon Lafer, a labor scholar, painted an alarming picture in a November 2021 report published by the Labor Education & Research Center at the University of Oregon, in which he compared the democratic standards in federal and NLRB elections.

“When most people hear that there is such a thing as union ‘elections,’ they assume these must be conducted in accord with the same democratic standards that Americans apply to all other elections,” Lafer wrote. “Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth…. Union elections conducted under the National Labor Relations Act fail to uphold the most basic standards of American democracy.”

In a federal election, it would be illegal (unthinkable, even) for one party to force voters to attend partisan meetings. But U.S. employers hold compulsory “captive audience” meetings, which workers are forced to attend to hear speeches denigrating unions that are delivered by union avoidance consultants.

“We were forced into what they called ‘union education’ meetings,” Bessemer worker Jennifer Bates testified before the Senate Budget Committee last March . “We had no choice but to attend them. They would last for as much as an hour and we’d have to go sometimes several times a week. The company would just hammer on different reasons why the union was bad. And we had to listen. If someone spoke up and disagreed with what the company was saying they would shut the meeting down and told people to go back to work. Then follow up with one-on-one meetings on the floor.”

In a federal election, it would also be illegal for different parties to have unequal access to voter lists, Lafer notes. But in a union election, the employer has full access to workers’ contact information from the date of hire, giving them ample opportunity to campaign against the union even before the campaign has gone public. To obtain workers’ information, unions must first gather signatures for a 30 percent showing of interest to petition the federal labor board for a union election. Unions must gather these signatures without any knowledge of how many workers are employed at the company or their contact information.

An employer can also gerrymander the voting district, or the bargaining unit, with workers who are anti-union or exclude those workers who are pro-union. In the first union election, Amazon quadrupled the size of the bargaining unit from 1,500 to 5,800 workers. In Staten Island, the company inflated the bargaining unit size to as many as 8,300 workers. Employers also routinely threaten employees’ livelihood during a union election; the RWDSU alleges that Amazon threatened to shut down the Bessemer plant if the union won.

Consultants abound to guide employers through this arsenal of antidemocratic weapons. Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of labor education research at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, has found that three-quarters of large employers hire anti-union consultants, spending hundreds of millions a year on that industry.

As promotional union-busting material by the law firm Jackson Lewis boasts, “winning an NLRB election undoubtedly is an achievement; a greater achievement is not having one at all.”

Amazon spent $4.3 million on anti-union consultants to defeat union efforts during 2021.

Even when legal protections exist, they are routinely violated. Lawyers can drag things out for years, and penalties are too low to deter employers. A 2019 report by the Economic Policy Institute found that nearly 20 percent of employers were charged with illegally firing pro-union employees, and over 40 percent with violating workers’ legal rights.

Bronfenbrenner says allegations of labor law violations occur throughout various phases of a union campaign, also including interrogation, firings, surveillance, bribes, changes to benefits, harassment, and discrimination.

“I’ve been studying this for thirty years,” she told Bolts. “And what employers do hasn’t changed. Every single management training manual has in it ‘tips’ in huge capital letters where they say what not to do, which is of course what to do: threats, interrogation, promises, coercion, harassment, and surveillance.”

Bronfenbrenner says she wonders about “all the campaigns that don’t get off the ground and all unfair labor law practices we don’t even find out about because workers never got in touch with a union.”

Proposals to strengthen workers’ legal rights, which have considerably eroded since the National Labor Relations Act passed in 1935, have stalled repeatedly, including when the Democratic Party has run the federal government. The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would create more favorable conditions for organizing and make mandatory captive audience meetings illegal, was a legislative priority for unions during the Biden administration, and it passed the U.S House in March 2021, but it lacks the votes in the U.S. Senate given the continued requirements that legislation earn a supermajority.

Jennifer Abruzzo, who has the power to set labor guidelines as the general counsel of the NLRB appointed by President Biden, has set her sights on strengthening unionization procedures without congressional action by reviving a rule known as Joy Silk. The rule stipulates that a company deemed to have engaged in unfair labor practices for the purposes of blocking a union’s organizing campaign can be ordered to recognize and bargain with that union if most workers had signed cards to affiliate and requested recognition from the company.

But for Chris Brooks, field director for the NewsGuild of New York, the nation’s largest journalism union, the fact that unions must fight to be recognized in the first place already distorts workers’ power. Bringing democracy into the workplace, he says, would mean recognizing that “they should all have unions” and treating that as just a starting point.

He is struck by the fundamental asymmetry that the country tolerates between employer and employee. Our basic conceptions of what it means to have fair elections—candidates enjoy a similar footing from which they compete for votes, which makes the results legitimate—become irrelevant in a unionization election where one of the parties is fighting for its very existence.

“The current system is not akin to living in a democracy and choosing between two competing political parties,” Brooks told Bolts. “It is more akin to living under a fascist dictatorship, where the employer is a private tyranny that routinely rigs elections to ensure that it will never face any kind of official and lawful opposition in the workplace.”