For Wisconsin Prosecutors, Elections in Name Only

DA candidates are running unopposed in nearly all Wisconsin counties this year, continuing a long streak of uncontested elections that cut off public debate on criminal justice issues.

| June 18, 2024

Planned Parenthood stopped offering abortion services in Wisconsin after the Dobbs decision in 2022, fearing that a 19th-century law would soon kick in and ban abortions in the state. Last fall, when a judge signaled that she would rule that the statute does not prohibit abortions, Planned Parenthood resumed its services in Madison and Milwaukee—but not in Sheboygan, the state’s only other city with a Planned Parenthood clinic. The local district attorney, Joel Urmanski, was fighting in court to preserve the abortion ban.

Urmanski eventually lost in court, enabling Planned Parenthood to resume its services in Sheboygan. But he has appealed the ruling; if successful, his legal challenge could still criminalize abortion in Wisconsin.

In the meantime, Urmanski won’t have to test his stance on abortion with the public. Sheboygan County hasn’t had a contested election for DA since 2002, and it won’t have one again this year. The filing deadline for candidates to run passed earlier this month, confirming that Urmanski won’t face an opponent as he seeks reelection; he’s never faced one in his past bids, either.

In some regards, 2024 is a new era for democracy in Wisconsin: The state supreme court struck down the GOP’s legislative gerrymanders last year, enabling fairer maps, and candidates have rushed to run for the legislature. But that spirit hasn’t carried over into criminal justice elections.

Wisconsinites this year are electing their 71 DAs, powerful county officials with wide discretion over who gets prosecuted to what degree of severity. But voters only have a choice in four of those elections. Across the rest of the state, in 67 out of 71 DA races, just one candidate is running unopposed in both the primary and the general election.

This means that the final result is already known in a startling 94 percent of the year’s DA races, limiting what little public oversight and accountability exists for these powerful offices. These uncontested elections also immediately cut off any public debate that a competitive race could have sparked on issues rocking the state, like police oversight or abortion rights.

“It’s a missed opportunity for the public,” regrets Craig Johnson, a Milwaukee lawyer who is the board president of Wisconsin Justice Initiative, a group that advocates for criminal legal reforms in the state. “It’s a missed opportunity for the community to engage in the kind of conversation and discussion of ideas that would be helpful in trying to move the criminal justice system forward.”

“When someone is uncontested, they don’t tend to appear at candidate forums, they don’t tend to go out and campaign as much,” he said. “The conversation is not as vibrant and as vigorous as it would be if there were two candidates who had different thoughts.”

Even in Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s most populous county, a new prosecutor is poised to waltz into the DA’s office without facing any opposition. Incumbent John Chisholm is retiring, and Kent Lovern, a deputy DA under Chisholm, is the only candidate who filed to replace him. His website as of publication is not specific on policy, promising to be “tough on crime” while looking at alternatives to detention for low-level offenses; Lovern’s campaign did not reply to Bolts’ questions about how he’ll approach the job.

In seven other counties, the sitting DA is similarly retiring with one single candidate running in their stead, typically an assistant prosecutor who’s seeking to replace their boss.

Fifty-nine incumbents, meanwhile, are running for new terms unopposed in both the primary and general election.

That all leaves just four contested races: in Kenosha, Waukesha, and Washington counties, as well as in the sparsely populated district that joins Menominee and Shawano counties.

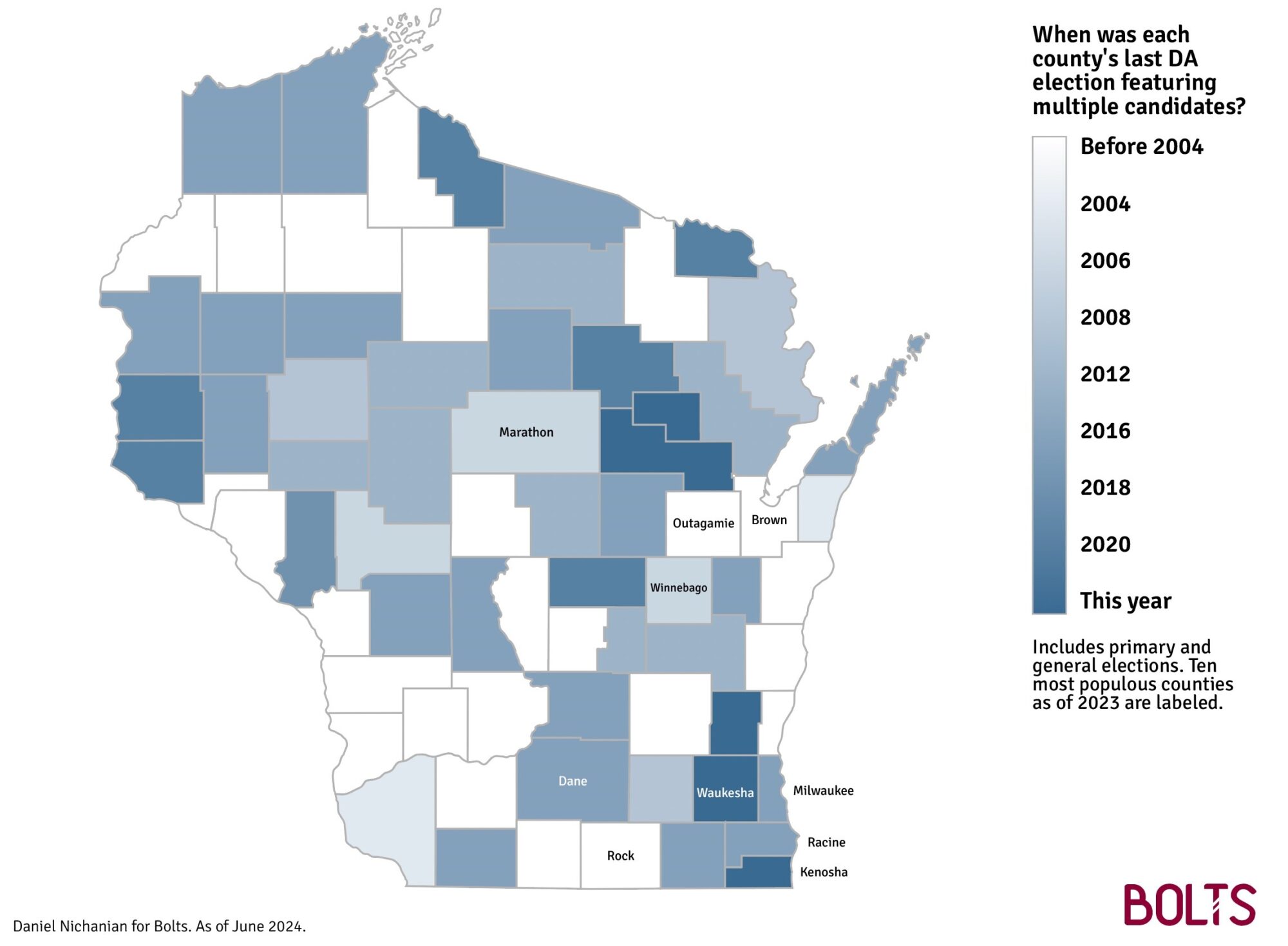

It’s common nationally for DA races to be uncontested. Still, the scope of this phenomenon in Wisconsin far surpasses what we see elsewhere. Four years ago, over 90 percent of the state’s DA elections drew just one candidate. And an analysis of past election filings by Bolts found that many Wisconsin counties haven’t held a single contested race in decades.

Most of the state’s DA offices—58 percent of the total—have seen no contested DA election in over ten years. That means that one candidate has run unopposed in the last three cycles.

In many cases, the streak goes back much further: More than one-third of Wisconsin counties have never held a contested DA race over the last two decades—a period that covers seven cycles of DA elections in the state.

Even in the counties that have experienced some competition, it’s still infrequent: Out of the seven election cycles from 2004 to 2024, roughly two-thirds of Wisconsin counties have seen no more than one contested election.

And this isn’t just a dynamic in the sparsely populated parts of the state. Three of Wisconsin’s ten most populous counties have held no DA race with multiple candidates since at least 2002. None has held more than two.

Overall, one fourth of Wisconsin residents live in counties that have had no contested DA race since at least 2002.

“It’s a problem for democratic accountability, given DAs have so much power, when there isn’t a choice for voters in the vast majority of counties,” said Amanda Merkwae, director of advocacy at the ACLU of Wisconsin. “If residents of a county are fighting for transparency and accountability with the DA’s office, the primary avenue of democratic accountability is through an election every four years and having a choice at the ballot box.”

For Merkwae, the ongoing litigation around abortion rights in Wisconsin is a stark example of the powers of prosecutors. “Depending on some decisions that are pending, if there is a gray area in the law, it’s functionally up to DAs whether to criminalize someone for accessing reproductive health care,” she said. “There are so many issues outside of what people typically think of when they think of the power of a prosecutor within the criminal legal system.”

Wisconsin, for instance, has been ground zero for baseless conservative conspiracies about the 2020 presidential race, with some Republicans endorsing aggressive investigations into the election officials who oversaw the results. “When you think about election conspiracies and baseless allegations of voter fraud, it is the DA who has the power and discretion to potentially endorse those conspiracies with prosecutions,” said Merkwae.

Eric Toney, the Republican DA of Fond du Lac County, is known for aggressively prosecuting election crimes since the 2020 presidential election and the conservative conspiracies about the result. He also sought the ouster of the Wisconsin Elections Commission, and aligned himself with the investigations of former Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman, a far-right figure now on the outs with the state’s Republican leadership.

Toney is running for reelection unopposed this year for the third consecutive four-year cycle.

Prosecutors in Wisconsin also are responsible for making sure there are consequences for police misconduct but often ignore that oversight function. An investigation by Wisconsin Watch last month revealed that many DAs fail to track or adequately maintain “Brady lists” of police officers with a history of lying or misconduct.

Under Urmanski, the Sheboygan County DA’s office filed dozens of criminal cases last year that relied on the testimony of police officers with such a Brady determination, according to the Sheboygan Press. The office has also repeatedly tried to seal the police records showing misconduct when those officers appear in cases. Earlier this year, a local judge rebuked Urmanski’s office for routinely making these requests to shield police misconduct records from public scrutiny.

“At what point does the public have a right to know about this pattern of misconduct of police officers in this community that rises to the level of being exculpatory?” Samantha Bastil, the local judge, said at a criminal hearing in December. Bastil, a former prosecutor, said during the hearing that she had never seen a policy of sealing police misconduct records so routinely in her time working in the criminal legal system. Urkmanski did not respond to a request for comment.

Merkwae hoped for contested elections as an opportunity for the public to ask DAs about their commitment to police accountability. She also wants prosecutors to revise their bail policies to reduce the state’s ballooned local jails, where people are detained in dismal and often deadly conditions. “Even spending a few days in jail can have devastating, long lasting consequences for folks who are presumptively innocent, both for them and their families,” Merkwae said.

But state Republicans have attacked rules around pretrial detention in Wisconsin as too lax, successfully championing a referendum last year to make cash bail more restrictive.

Republicans have also assailed the outgoing DA in Milwaukee, Chisholm, over the case of Darrell Brooks, who drove a car through a Christmas parade in Waukesha County in 2021 while he was out on bond, killing six people. Chisholm has long touted his efforts to reform the county’s bail system and reduce incarceration, even if Milwaukee’s brutal local jail during his tenure has regularly been over capacity. After the Christmas parade attack, Chisholm said that the bail amount his office had recommended for Brooks in an earlier assault case was “inappropriately low” and not consistent with internal policies.

For Johnson, of the Wisconsin Justice Initiative, the response to such “sensational crime news” underscores why it’s difficult to persuade people with an interest in criminal justice reforms to run for DA. “You can expect to be attacked, you can expect to have every decision second-guessed, and you can expect probably to be recalled if there’s a decision that people disagree with,” he told Bolts.

“If you’re a prosecutor and you recommend a low bail on somebody, and that person pulls out and commits a bank robbery or shooting or something, it is going to get headlines,” he said, adding that it’s difficult to get similar coverage when reforms are successful. “If a person arrested on a burglary charge has mental health issues, and instead of being sent to prison, they’re put into some sort of program that gets them community-based mental health services, and as a result they connect up with a good program, they succeed, they go on to live a crime free life, that’s not going to be a big story. That’s going to be a quiet success.”

Darrol Gibson, the Wisconsin state director of Run for Something, an organization that recruits progressive candidates to run for local office nationwide, told Bolts that he’s always eager to find people who want to change the system and come from different communities than the average politician. But he says it’s particularly hard to find such candidates in DA elections, especially when it comes to recruiting candidates of color.

“Our justice system has not been kind to communities of color,” Gibson said, pointing to the record rates of incarceration for Black people in Milwaukee and in the state. “For me to fill this role, what do I have to put myself through to change the system? … Am I participating in the same system that I’m trying to fight against?”

Still, Gibson said he encourages people to think of the broader impact their candidacy could have even if they don’t prevail. He told Bolts that whenever he meets a candidate, he asks them, “What do you want to do in this election? What issues do you want to bring forth, what things we want to push your opponent to speak on and to take a stance on and hold him accountable to?”

Contesting elections isn’t just winning elections, he said, it’s about “moving the way people think and perceive what is possible.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom: We rely on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.