In Ohio, Uncontested Elections Worsen a Breakdown in Accountability for Prosecutors

The vast majority of prosecuting attorneys are running unopposed this year, despite the policy debates and misconduct allegations surrounding many of their offices.

Daniel Nichanian | January 19, 2024

Dennis Watkins, the prosecuting attorney of Ohio’s Trumbull County, sparked national outrage last month when he pursued criminal charges against Brittany Watts, a woman who miscarried at home and was then dragged into court when a nurse called the police on her. A grand jury declined to indict Watts last week, but reproductive rights advocates stress that Watkins’ choice to pursue the case reflects an escalating policing of pregnancies nationwide, fueled by local prosecutors’ power to target women who lose a pregnancy.

The controversy unfolded in the run-up to Ohio’s late December filing deadline to run for prosecutor in 2024. There was a brief opportunity for the state’s upcoming elections to test whether local prosecutors would commit to respecting the will of voters on reproductive rights. Residents of Trumbull County had just voted in November to protect abortion rights, approving a statewide measure known as Issue 1 by a margin of 14 percentage points. Its proponents blasted Watkins for betraying the measure’s “spirit and letter” in going after Watts (Issue 1 enshrined a “right to make and carry out one’s own reproductive decisions” in the state’s constitution).

But then the December filing deadline came and went, putting an immediate lid on that prospect.

No one filed to run against Watkins, who is virtually guaranteed to secure an 11th four-year term in November without needing to explain his actions to voters. (The deadline passed for people running as party candidates but independents can still file by March, though they rarely win such races in Ohio.)

In fact, Watkins has never faced a challenger in any of his other nine reelection bids since 1984. Over his time as prosecutor, he has fought to keep people with mental illness on death row, and in 2019, he defended a prosecutor in his office who frequently mocked defendants with crude public jokes, dismissing ethics concerns.

It’s the same scene around the state. Only 15 of Ohio’s 88 prosecutor elections this year drew multiple candidates by the December deadline, according to Bolts’ compilation in each county. This means that the vast majority of the state’s prosecuting attorneys are running unopposed this year; Bolts has confirmed that no more than one candidate has filed to run in 73 of the 88 counties.

Like Watkins, many of these prosecutors oversee offices that have faced misconduct allegations but have suffered no consequences from state officials. A recent investigation by multiple news organizations showed how failures by state agencies have allowed prosecutors across Ohio to get away with breaking the law to win convictions. The investigation detailed how one staff prosecutor repeatedly violated defendants’ rights while working for three Ohio counties over the last two decades but continued to be employed. In each of these three counties, the incumbent prosecuting attorneys—Lucas County’s Julia Bates, a Democrat, Ottawa County’s James VanEerten, a Republican, and Wood County’s Paul Dobson, also a Republican—are running unopposed this year.

When there’s a lack of top-down oversight, elections can offer an alternative mechanism of accountability, forcing officials to defend their actions and create some path for an official’s removal. But that all hinges on people actually running.

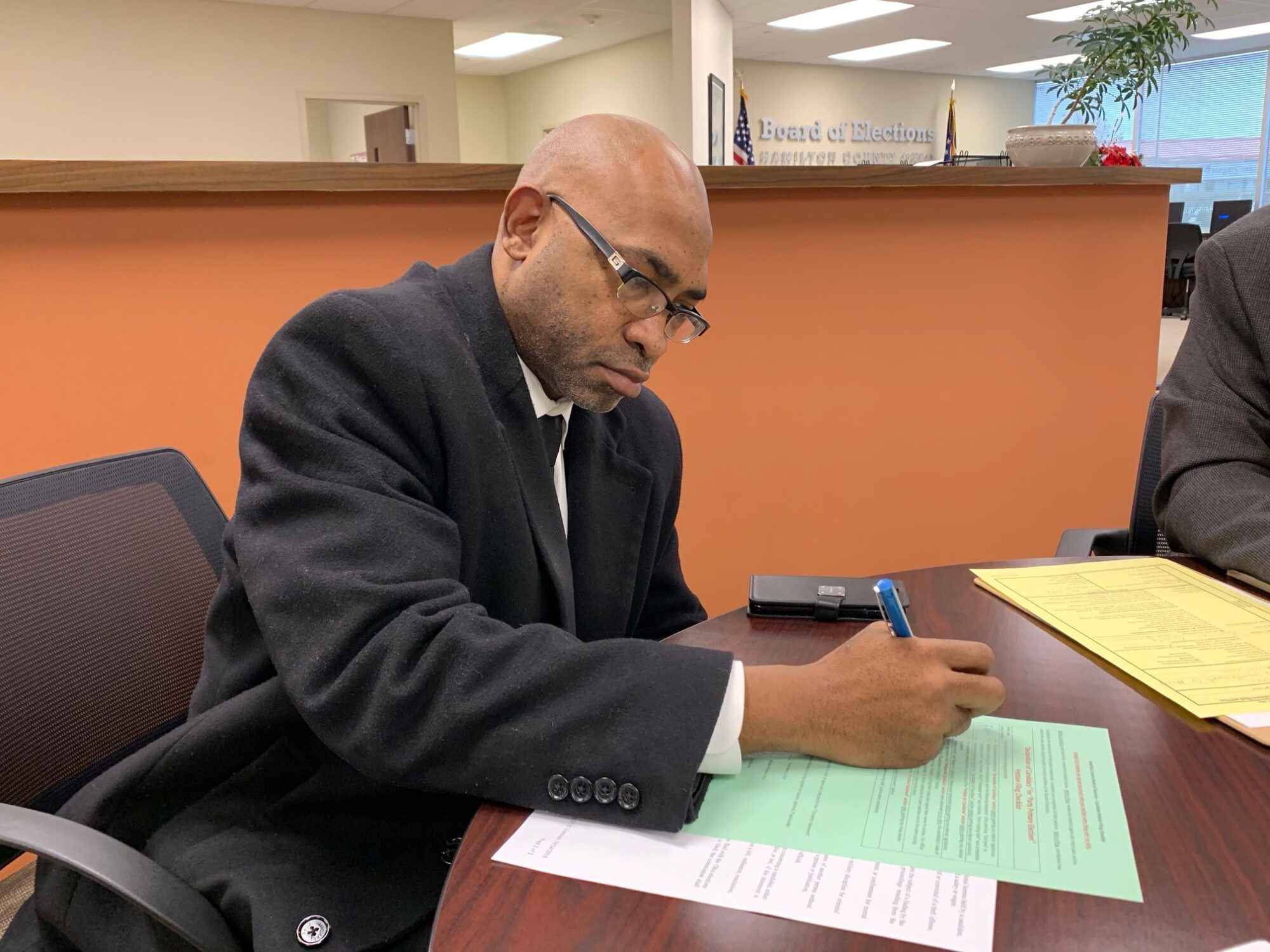

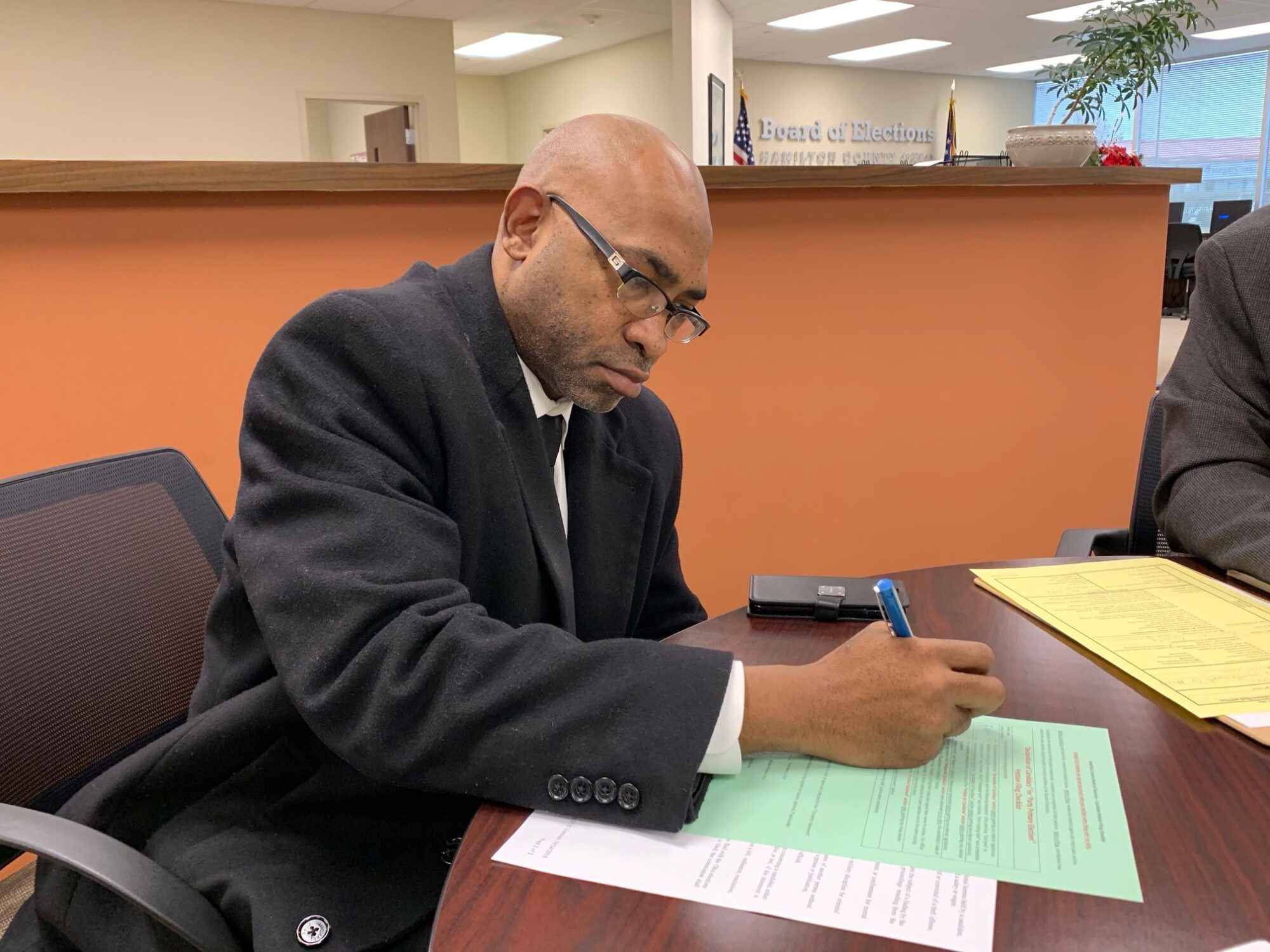

Fanon Rucker, an attorney who unsuccessfully ran for Hamilton County prosecutor in 2020, referenced many prosecutors’ failure to even set up conviction integrity units to investigate possible errors and correct wrongful convictions despite the misconduct allegations they face. “If a person is running unopposed and doesn’t feel like that’s a priority, then who’s going to hold their feet to the fire?” he asked. “Who’s going to speak to the community to have them unelected if they don’t take on those types of projects? “

To be sure, Ohio’s most populous counties are more likely to see contested prosecutor elections this year.

Unlike in 2020, each of Ohio’s three largest counties have more than one candidate filed for the race. In Franklin County (Columbus), the incumbent’s retirement has triggered a four-way race, with the winner of the Democratic primary likely favored to take the job. In Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Republican Prosecuting Attorney Melissa Powers faces Democrat Connie Pillich, a former state lawmaker. And in Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), progressive law professor and former public defender Matthew Ahn is challenging Democratic incumbent Michael O’Malley in the March primary.

Still, the lack of candidates is in no way constrained to smaller rural counties. Of the 27 counties with more than 100,000 residents in Ohio, 70 percent drew just one candidate. Watkins’ Trumbull County, southeast of Cleveland, has 200,000 residents. Bolts’ analysis shows the majority of Ohio’s population lives in counties with uncontested races.

Four years ago, even O’Malley ran unopposed in Cleveland. Ahn, who is challenging him this year, says he was shocked at the time to see the race was uncontested, especially given the punitive turn O’Malley’s took during his first term. “We saw a drastic increase in the number of children tried as adults, we saw the county issue more death sentences than any other county in the United States, and so I was really interested in who was going to challenge O’Malley in 2020,” Ahn told Bolts. “The answer to that question ended up being nobody.”

Ahn tried gauging local acquaintances’ interest in challenging O’Malley this year. “By and large, the most common response was, ‘I’m not challenging the machine,’ or ‘Nobody can beat the machine,’” he said. “After hearing this over and over again, I thought it was unacceptable for O’Malley to go uncontested two cycles in a row.”

In running, Ahn says he’s at least forcing a public debate about local criminal legal policies. “I thought that just even having this conversation is a public good for the voters of Cuyahoga County, for us to think about how we can actually promote public safety,” he said. His campaign blocked O’Malley from securing the local Democratic Party’s endorsement at a convention this month.

It’s unusual enough for any candidate to challenge an incumbent prosecutor in Ohio. It’s even rarer for one to do so while proposing criminal justice reforms—like Ahn, who promises for instance to never seek the death penalty and reduce adult prosecutions of minors.

Prosecuting attorneys tend to vocally fight reform proposals regardless of their party, which has occasionally clashed with the politics of Ohio’s GOP-run legislature. Some Republican state lawmakers have teamed up with Democrats to introduce major reform legislation, but these bills typically run into a bipartisan wall of opposition from prosecutors.

In 2021, for instance, Republican Governor Mike DeWine signed a bipartisan bill that limited the use of the death penalty against individuals with mental illness. Prosecutors from both parties, including Cuyahoga County’s O’Malley, fought the bill’s passage. The same year, Ohio also adopted a bipartisan bill that abolished life sentences without the possibility of parole for minors, over the opposition of the Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association, an organization that lobbies lawmakers on behalf of the state’s 88 prosecuting attorneys.

“They’re pretty much in lockstep, they’re pretty much in unison,” said Kevin Werner, who supported that death penalty bill as policy director at the Ohio Justice & Policy Center, an organization that advocates for criminal justice reforms. He says prosecutors from both parties band together regardless of who supports a reform proposal. “If it’s a bill that intends to increase the penalty, or increase the duration that a person could be sentenced to incarceration, they’re in favor of it,” Werner told Bolts. “If it’s a bill that rolls back any of those kinds of things, they’re opposed to it as sure as the sun will rise.”

“They’re often trying to change the standards of proof, making it easier to secure a conviction,” he said. “They want to make their jobs easier.”

Elsewhere in the nation, victories by reform-minded candidates have changed this dynamic and led to policy disagreements among prosecutors. Ohio is far from that, but Ahn hopes to break the mold of the typical prosecutor. He thinks his background as a former public defender gives him a “different experience and a different perspective on the justice system” than voters usually hear from prosecutor candidates.

“There still is this political assumption that, in order to win, you have to be 90s-style ‘tough on crime’ elected officials,” Ahn said. “What I’m finding in my conversations with folks across the county is that’s not necessarily true. But for folks who come up within prosecutor’s offices and then themselves run for prosecutor, these assumptions are often still accepted as a fact.”

Rucker says his 2020 run for prosecutor in Hamilton County, a metro area that includes Cincinnati, was a lesson in how bruising local elections can be.

“This is the single most powerful position in the county because of the discretion, because of the influence, because of the relationships,” Rucker said. “You have to raise a lot of money, and you have to have an equal amount of influence and authority as the incumbent that you’re running against.”

As a longtime local judge, Rucker says he felt he had the standing to pull off a campaign. But many attorneys who want to challenge a sitting prosecutor anywhere in the state may be afraid of making a powerful enemy who can have enormous impact on their careers. “‘If I run and lose, how will this affect my financial bottom line, or even the outcomes of my cases?’” Rucker said.

These same dynamics exist throughout the nation, making it common in nearly every state for only a fraction of prosecutor elections to be contested. But the dearth of prosecutor candidates in Ohio this year still stands out even by national standards. In the 2023 cycle, for instance, roughly a third of elections in Mississippi and Pennsylvania drew multiple candidates; half did in New York.

Numerous factors can contribute to this scarcity of prosecutor candidates. Besides the fear of retribution, some Ohioans who talked to Bolts for this article spoke of difficulties fundraising, and said a general political apathy has set in due to the lack of competition for control of the state government as a result of practices like gerrymandering.

Rucker, who is Black, said racism in politics may also weigh on the minds of people of color who consider running. He pointed to attack ads his Republican opponent, incumbent Hamilton County prosecutor Joe Deters, unleashed in the final weeks of the 2020 campaign that tied Rucker to some activism born of the summer’s Black Lives Matter protests.

“An angry Black man who was tied into rioting groups who were going to come to the city and beat and rape women, and start fires and riots—that was the messaging, and that was the imagery in their ads,” Rucker told Bolts. “It was intended to emotionally sway suburban white women, Democrats and Republicans.”

Rucker, who denounced the ads as “race-baiting” at the time, lost to Deters by five percentage points, even as Democrats won nearly all other county-wide offices.

“I was gonna be successful if it hadn’t been for some racist crap, which also may deter some folks from getting into races, particularly minorities,” Rucker said.

Shortly after the election, Rucker received a letter from a Hamilton County voter explaining why she voted for every Democrat on the ticket but him. The letter, which Rucker says he keeps on display in his office, affirmed his suspicions of how racism contributed to his loss.

“Mr. Rucker, I would not vote for you because you scared me,” the voter wrote. “When I watched your ads, all I saw from your deameanor [sic] was an angry, militant, black man. All I could think was that you would promote those traits.”

Deters, Rucker’s 2020 opponent, resigned in early 2023 to become a justice on the Ohio supreme court. Powers, his replacement, has already warned of rampant crime if she were to lose. Her campaign website says of the prosecutor’s office, “It is simply too important to let it fall into the hands of soft-on-crime criminal advocates.” Powers is uncontested in the GOP primary; in November she will face Pillich, a white Democrat.

In April, Powers warned of more liberal candidates transforming Cincinnati into “a Baltimore, a Saint Louis,” two cities known for having large Black populations. “That’s veiled, stereotypical race baiting and fear mongering,” Rucker said.

Rucker says he stayed out of this year’s prosecutor race because he’s enjoying his new work in private practice. But he also said he did not want to revisit the sort of attacks he suffered four years ago.

“It took everything in me to hold my peace during that time and not cuss everybody out, and the second time I would,” he told Bolts. “I have zero interest in being resubjected to the kind of racially hostile messaging that was so very clearly central in the outcome of that previous campaign. Not interested. I’m enjoying my life too much.”

This article has been updated with information on the one county that had not shared its candidate list nor replied to our request by our deadline. Its prosecutor race turned out to be uncontested as well.

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.