Mississippi Power Grab Heightens Focus on State’s Punitive Court System

But the state’s next DA elections, around the corner, again bring few electoral openings to reform the status quo.

Daniel Nichanian | February 10, 2023

Editor’s note (April 24): House Bill 1020 was signed into law by Governor Tate Reeves on April 21.

Mississippi Republicans this week advanced a bill that would carve out a new judicial district within the capital city of Jackson. It would wall off predominantly white sections of the majority-Black city from the control of its elected Black leaders and create a new court system with prosecutors, judges, and police appointed by the state’s white leaders.

The effort has sparked an outcry among local residents and advocates that champion racial justice. “House Bill 1020 is one of the most radical pieces of legislation I have seen in 30 years of practicing law in Mississippi,” said Cliff Johnson, a professor at the University of Mississippi School of Law who is also the state director of the MacArthur Justice Center.

“You will have a handful of conservative white politicians in Mississippi controlling large swaths of the capital city,” he added.

For Nsombi Lambright, executive director of One Voice Mississippi, the push for HB 1020 is about maintaining two systems of justice. “Now, if you arrest people, they have to answer to the court system within Hinds County [Jackson], and individuals have been elected to run those systems, our DA and our public defender systems, and our judges,” she said. “But this undermines that system completely.”

But those advocates also say that the bill captures a broader fight over efforts to tighten the criminal legal system’s grip in Mississippi, a state already in the throes of a record prison population, yearslong pretrial detention, and the rising criminalization of abortion. The state’s next round of elections for prosecutor, a position with great discretion over these issues, are fast approaching but will offer few opportunities to even debate them.

Mississippi leads the way on a global scale in the share of its residents that it puts behind bars. That record disproportionately falls on Black Mississippians, who make up nearly two-thirds of the people in state prisons. A staggering 16 percent of Black adults were barred from voting in last fall’s midterms due to a felony conviction, as was 8 percent of the rest of the population.

The Republican sponsor of HB 1020, Trey Lamar, a white lawmaker who represents a county far from the city, has said he introduced the bill because he is motivated by the crime rate in Jackson. “My constituents want to feel safe when they come here,” he told Mississippi Today.

But Lambright faults state leaders who, though quick to talk of a public safety crisis, ignore obvious initiatives that would slash the root causes of crime like poverty. Republicans, who maintain a steady control of the state legislature and governor’s mansion, have refused to expand Medicaid for low-income residents as enabled by the Affordable Care Act for a decade now. This is denying public insurance to over 200,000 residents, who are disproportionately Black.

Bills to expand Medicaid all died without a vote in the legislature this month. Instead, with HB 1020, lawmakers turned to funding a new bureaucracy and expanding the reach of the Capitol police, a force that has terrorized Jackson and would now be even less accountable to its Black leadership. The new district would also have exclusive authority to hear all lawsuits brought against the state, making it harder for civil rights groups like One Voice to press legal claims.

“Lack of health care, a poor educational system, poor access to mental health. It all feeds into what we’re seeing now,” Lambright said. “I’ve been around for years and years and years, and Jackson leaders have asked state government for assistance with crime, with school districts, with the water system, with infrastructure, with everything, and the state has said, ‘No, you’ll figure it out,’ and now all of a sudden, there’s this big interest in Jackson.”

The bill passed the state House on Tuesday, shortly after the Feb. 1 filing deadline for the state’s district attorney elections (all counties vote for their DA this year). The juxtaposition brought into sharp relief how odd it is to subtract just a select few neighborhoods from the rule of having elected prosecutors.

But the state’s recent history helps explain white conservatives’ defiance toward those elections.

In Mississippi’s most recent DA races in 2019, several candidates won on platforms that stressed an explicit goal of reducing incarceration. It “was the first time you had heard candidates talk in that language,” says Lambright.

But with that has come a crackdown. One of those DAs, Jody Owens, was elected in Jackson’s Hinds County. He is the one who now stands to lose authority over some of the territory he was elected to lead—and some of the cases he currently oversees—if HB 1020 passes.

“This is a blatant attempt to steal the right to vote and elect officials from the citizens of Hinds County,” Owens tweeted last week. “All citizens of Hinds County and the State of Mississippi should be alarmed at the attempted disenfranchisement of citizens.”

Back in 2019, Owens said state prosecutors were too prone to seek “more incarceration time” as “the only tool they have” and that he wanted to scale back some sentences, especially for drug offenses. In July of 2022, he joined another first-term Black prosecutor, Shameca Collins, who represents a rural district south of Jackson, to sign a letter pledging to not prosecute cases relating to abortion. Their announcement came one week after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned federal protections for abortion in a case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, that challenged Mississippi’s new restrictions on the procedure.

The building that housed the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, an abortion clinic within Jackson that closed in July, is situated within the boundaries of the court system that would be set up by HB 1020. For Johnson, reproductive rights are part and parcel of the battle over the bill, which would hand over some of Owens’s authority to an appointed prosecutor.

“This new court would hear cases brought by a prosecutor who was hand picked by Attorney General Lynn Fitch, the person who led the fight to overturn Roe,” Johnson said.

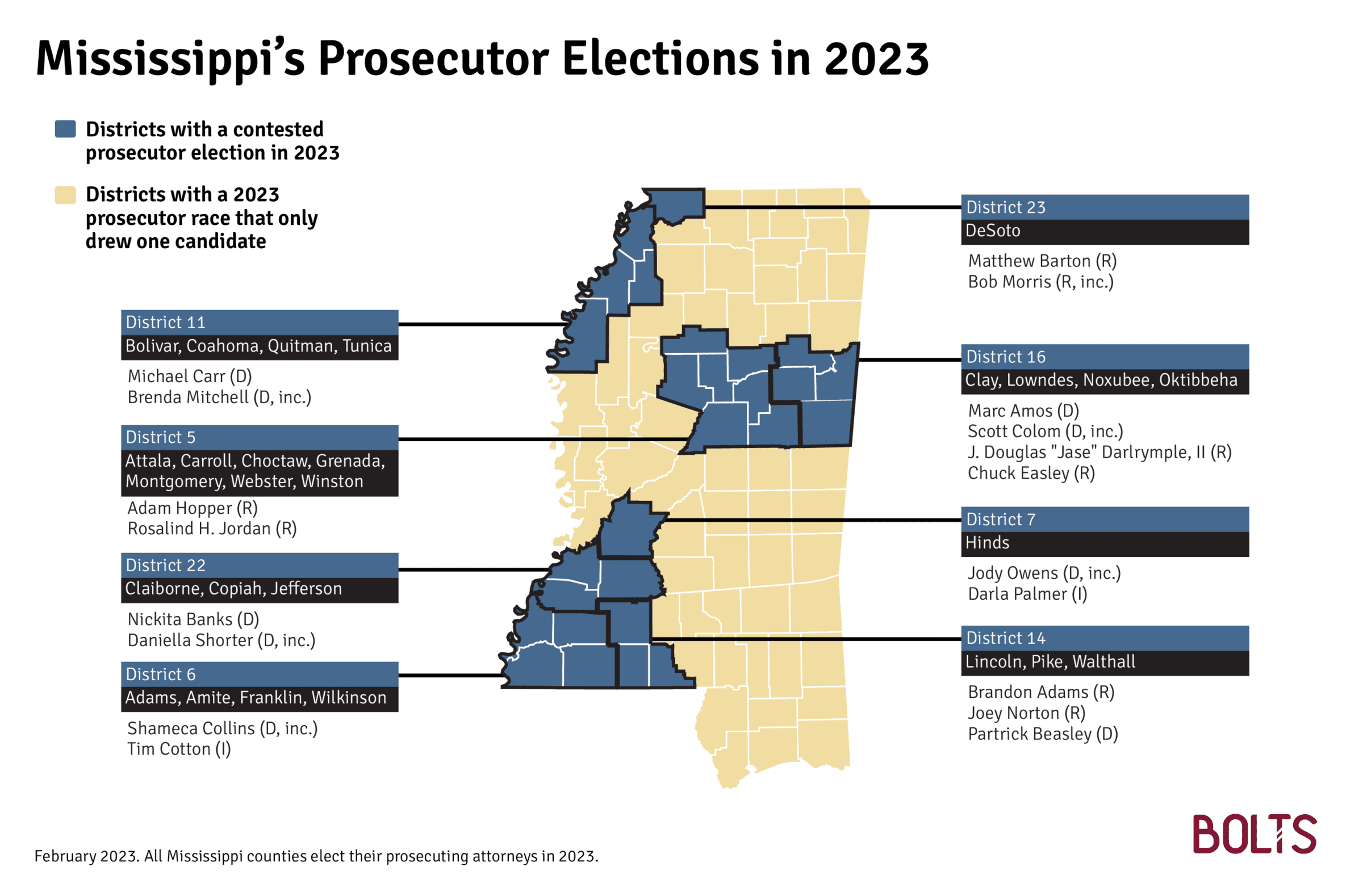

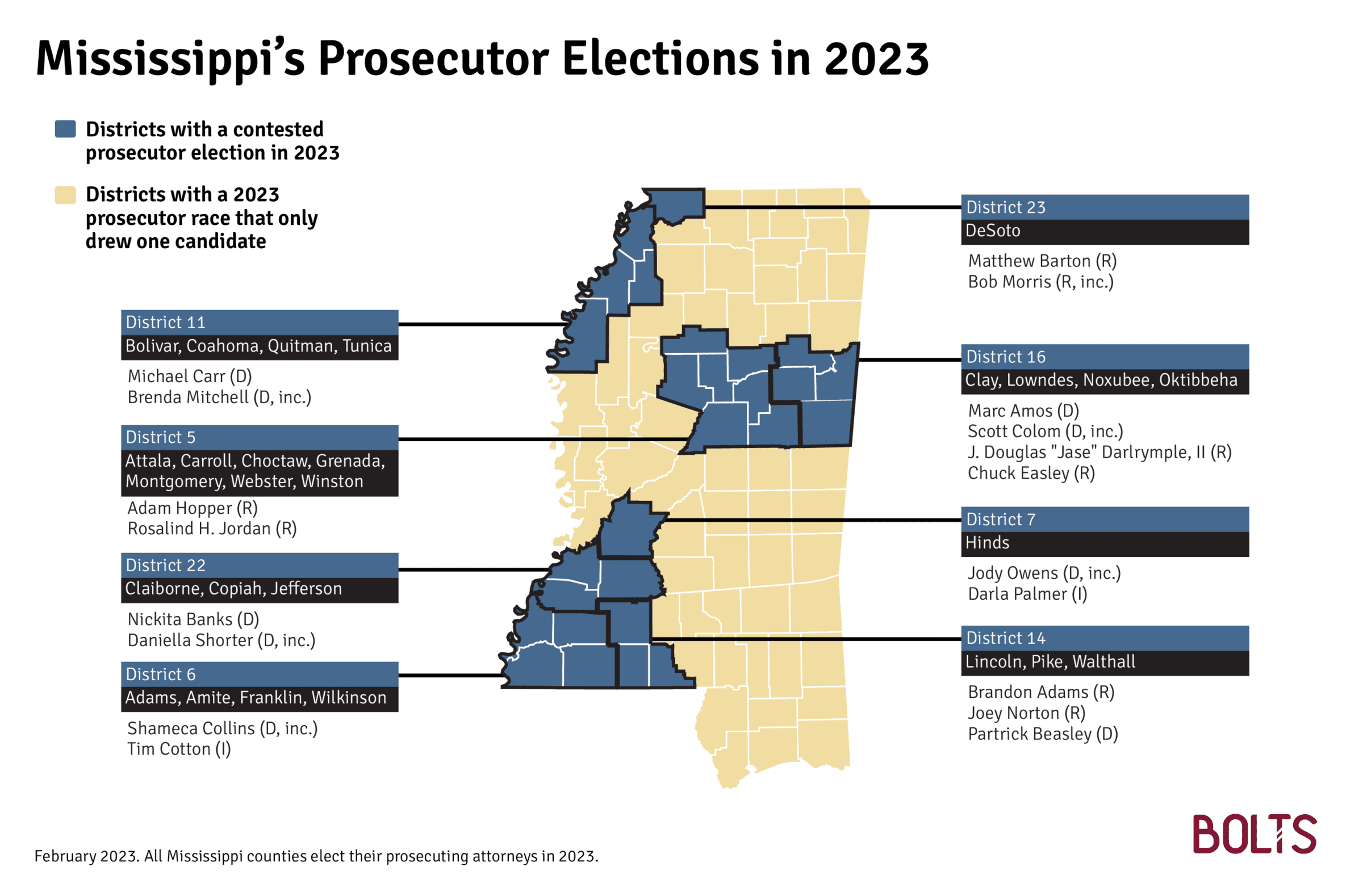

Owens and Collins are both Democrats, and each drew one opponent this year. Collins’s opponent, independent candidate Tim Cotton, did not reply to questions on his views.

Owens is facing a rematch against Darla Palmer, a Jackson attorney whom he defeated in a Democratic primary four years ago. Soon after his win, Owens faced sexual harassment allegations, reported by The Appeal, at his workplace. This year, Palmer has chosen to run as an independent.

When asked about Owens’s policies, Palmer told Bolts via email that she had “no comment on prosecution regarding abortion laws.”

She otherwise picked up on her last campaign, during which she criticized Owens’s talk of reform. Voters should elect someone who will “send out a valid message that crime deserves punishment which includes incarceration,” she told Bolts.

She joined Owens in denouncing HB 1020, calling it “disingenuous and divisive,” while also blaming its introduction on what she called the incumbent’s “failure.”

Owens and Collins’s districts both lean Democratic, likely giving them a leg up in the race. Primaries will be held in August, and the general elections in November.

Still, the final field of candidates revealed few opportunities this year for other DAs to be elected in Mississippi with a stated goal of reducing incarceration or not prosecuting abortion.

Of the state’s 21 other DA races (which often feature multi-county districts), 15 feature an incumbent who is running entirely unopposed. Another, the blue-leaning 16th district, is in an unusual situation in that incumbent Scott Colom’s only Democratic rival told Bolts that he only filed for office in case Colom gets confirmed to a federal judgeship by the U.S. Senate in the coming months. (Colom was nominated to the bench by President Biden.)

Of the remaining five districts, some pit candidates trying to sound “tougher” than the other, a conventional template for DA elections. In the central Fifth District, vacated by Doug Evans—a longtime, white DA who became notorious nationally for his crusade to bring a Black man named Curtis Flowers to trial six separate times for the same alleged crime—one of the two candidates is Evans’s chief deputy Adam Hopper, last seen seeking to deny Flowers bail and continuing to press the case.

“In this state that locks up more people than any other state in the country,” Johnson told Bolts, “it is exceedingly rare for any candidate to raise or mention the proposition that perhaps this system of mass incarceration isn’t working, that perhaps lengthy jail sentences are not working, and that perhaps we should focus on the root causes of behavior we don’t like rather than waiting for people to to mess up and then knock them in the head.”

“Instead they focus on ways they can take the existing criminal legal system and bludgeon more people,” he said.

All in all, Bolts reached out to nine new candidates—leaving aside some who do not have public campaign information as of publication—to learn about the approach they would wish to take if elected.

Only one, Michael Carr, a lawyer running in the rural 11th District in northwest Mississippi, unequivocally shared a view that incarceration is too high in Mississippi. “Crime rates in Mississippi have not gone down, though our prison population has gone up,” he said. He also said he would not prosecute cases relating to abortion, if elected.

He is challenging incumbent Brenda Mitchell in the Democratic primary. Mitchell did not respond to questions about her views on incarceration, abortion and other issues.

Carr, who now works as a defense attorney, says he is frustrated to see his clients spend extraordinarily long periods in jail. “You can sit in jail for years pretrial, which means you’re not guilty of anything,” he said.

People in Mississippi are routinely held in jail for months, and often for over one year if not multiple years, before any trial. The length of detention is high in virtually all counties in the state, according to data collected by McArthur Justice Center; in each of the four counties that make up the 11th District, the median duration ranged between five and ten months in 2021.

Carr said he would push for speedier trials and offer more plea deals to achieve that, though people in such situations can feel coerced into guilty verdicts in exchange for their freedom. He also pledged to increase the use of pretrial diversion for cases that come to him in order to reduce the number of people who end up with a felony conviction. “You are creating a class of people who suddenly have an amazing inability to generate income, therefore cannot provide for their family, therefore, turn back to crime,” Carr said.

Besides cutting people off from employment and the ability to hold a swath of licenses, most felony convictions in Mississippi deprive people of their right to vote. In this state, unlike in most others, that loss is permanent—an exclusion that affects hundreds of thousands of people.

As a result, the people who have the most direct experience of the workings of Mississippi’s court system and of its extremes are barred from shaping what it should look like.

The same Mississippi advocates now fighting HB 1020 for kneecapping self-governance in Jackson with racist motives have also long combatted felony disenfranchisement for doing the same. And they are stepping up their warning against antidemocratic schemes.

“We are just disgusted with that law,” Lambright said of the state’s felony disenfranchisement statutes. “We can actually change elections if that law would be overturned.”