In the South, Challenges to Democratic Prosecutors Headline November’s Elections

Bolts’ overview of 2023 DA races continues in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Virginia, amid escalating efforts to undermine the results of prosecutor elections in the region.

| August 14, 2023

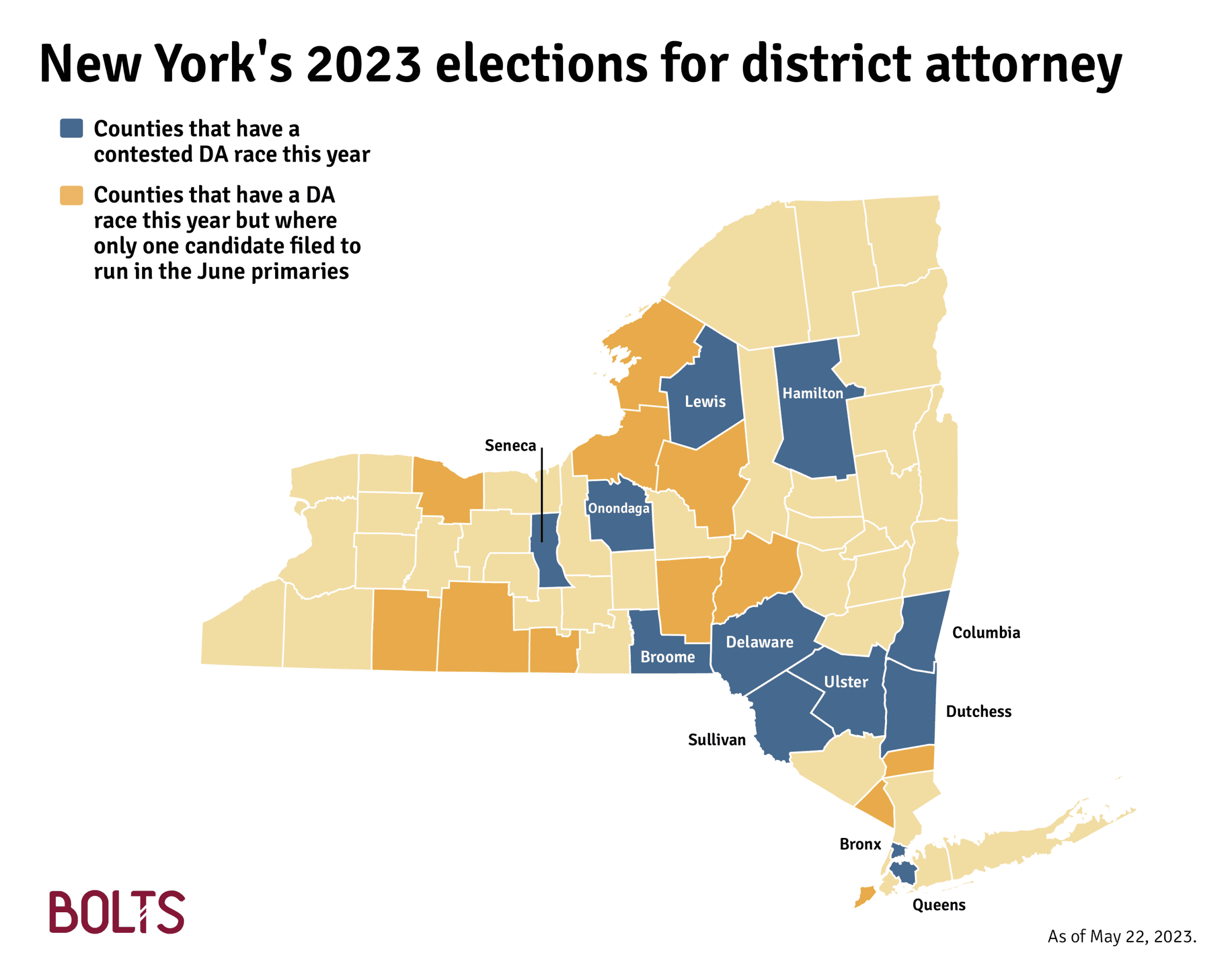

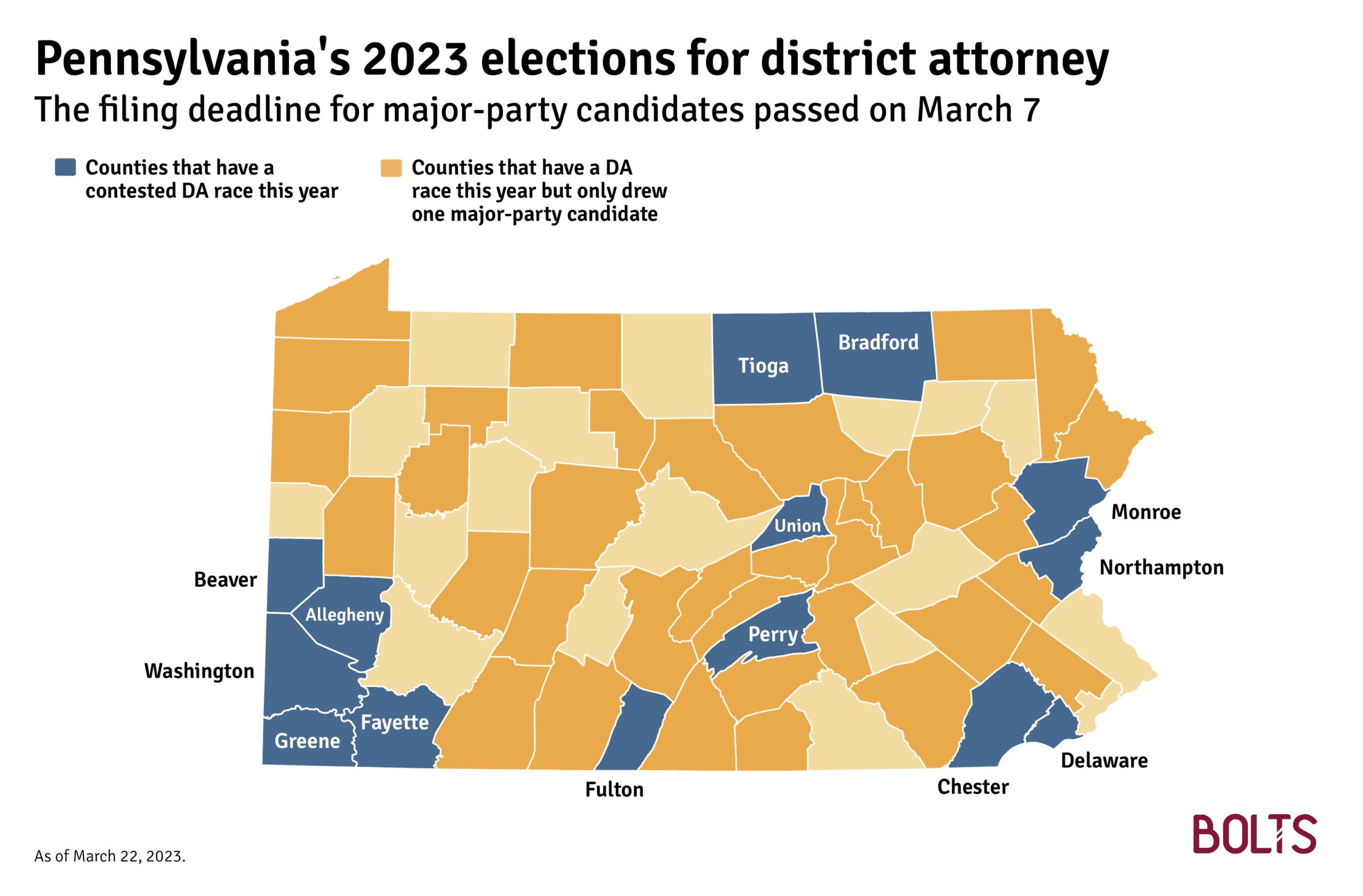

This article is the final installment of Bolts’ statewide primers on 2023 prosecutor elections. Read our earlier primers of all DA races in New York and in Pennsylvania.

Voters in the South will elect dozens of local prosecutors this November. But the proceedings are overshadowed by Southern state governments’ escalating maneuvers to undercut the will of voters in prosecutor races—fueled in part by Republican anger against some prosecutors’ policies of not enforcing low-level charges and new abortion bans.

Mississippi this year removed predominantly white sections of Hinds County, the majority-Black county that’s home to Jackson, from the control of its Black district attorney. Georgia reacted similarly to recent wins by DAs of color: It cut off a white county from a circuit that had elected a Black prosecutor, and also set up a new state agency with the power to fire DAs. Last week, Florida Republican Governor Ron DeSantis suspended Orlando’s elected Democratic prosecutor, citing disagreements with her office’s approach to prosecution, one year after he similarly replaced Tampa’s Democratic prosecutor with a member of the Federalist Society.

These rapidfire events are exacerbating the question of what it even means to run for office when your win could be undermined so easily, or when your winning platform might be turned into a reason to remove you from office.

Still, the electoral cycle churns on. There will be 123 local prosecutor races across Kentucky, Mississippi, and Virginia—the only three Southern states voting on this office in 2023.

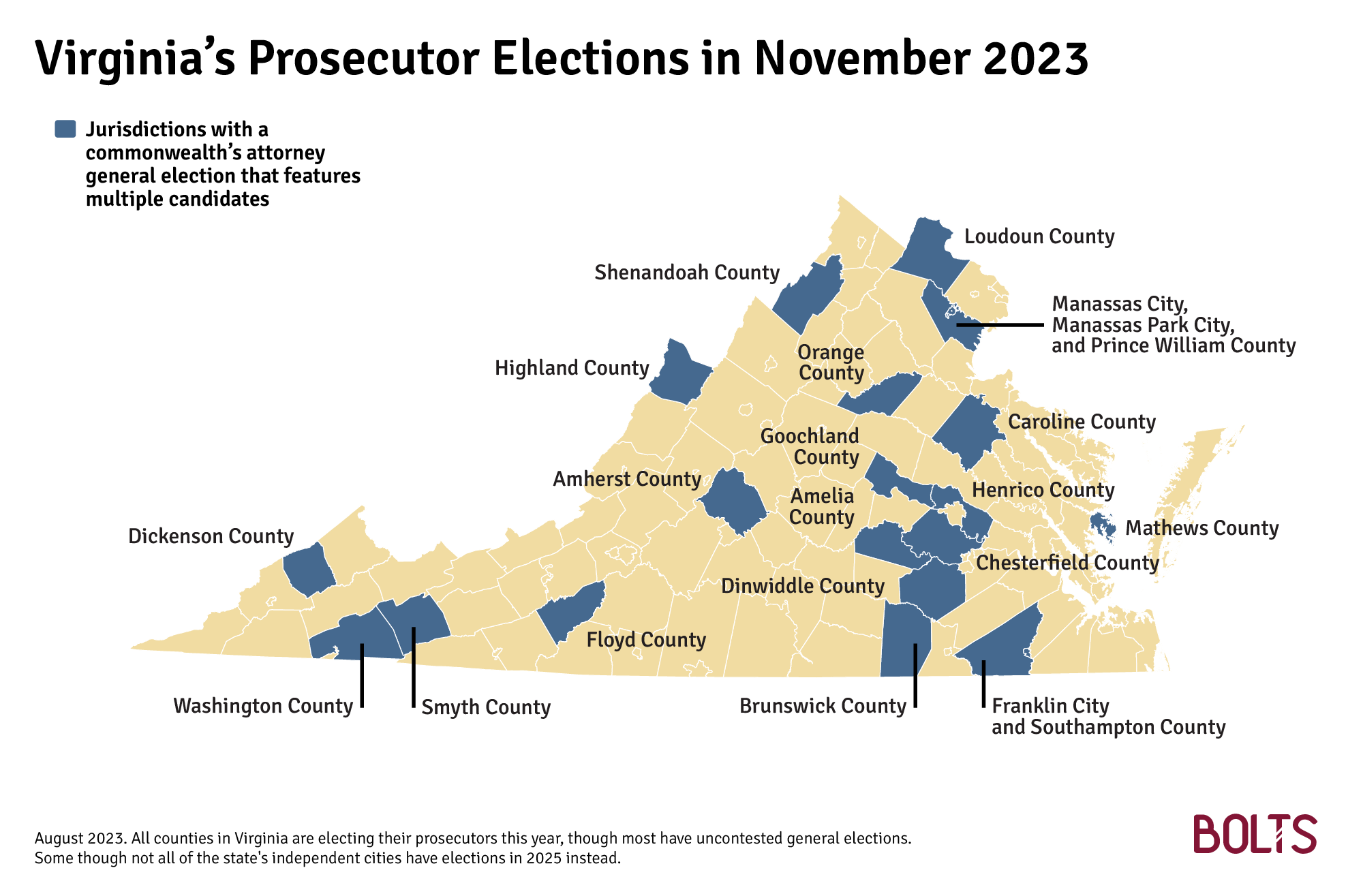

The lion’s share is in Virginia, a state that may soon experience its own version of this dynamic. Republican officials have wanted to crack down on reform prosecutors but have not been able to push their proposals through so far; they may try again in 2024 if they gain the legislature. In the meantime, these policy debates are playing out in a more usual place—the electoral arena.

In three populous Virginia counties, Republican candidates are defying three Democratic prosecutors who joined calls to reform Virginia’s criminal laws while their party briefly ran the state in 2021 and 2022. In making the case that crime should be prosecuted more aggressively, these challengers are mirroring candidates who already ran—and lost—against other reform prosecutors in the June Democratic primaries.

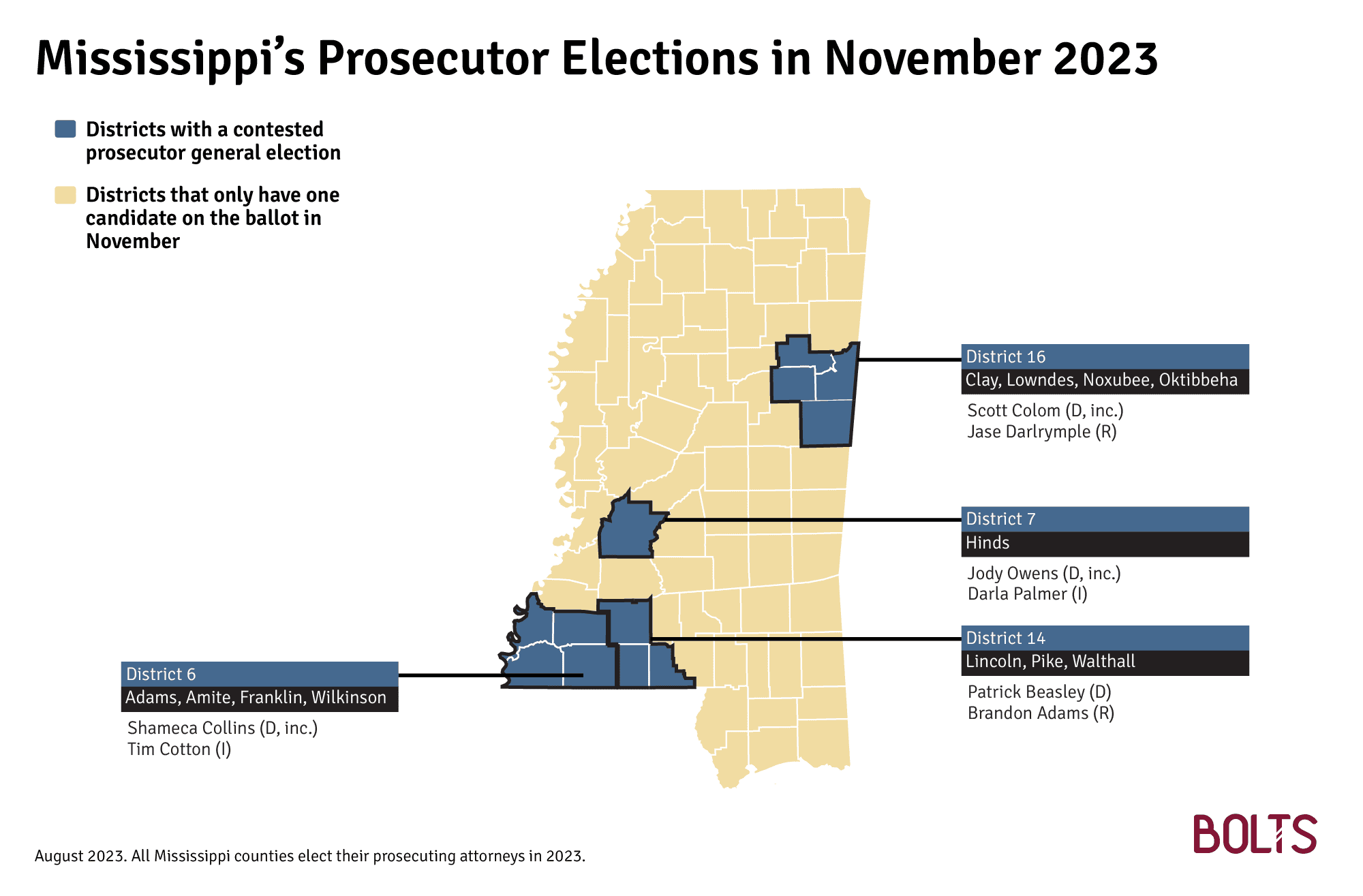

Mississippi also features challenges to three Democratic prosecutors who have, to varying degrees, implemented some priorities of criminal justice reformers, such as expanding alternatives to incarceration or vowing to not prosecute abortion cases. Their opponents have indicated that they wish to reel back some of these efforts.

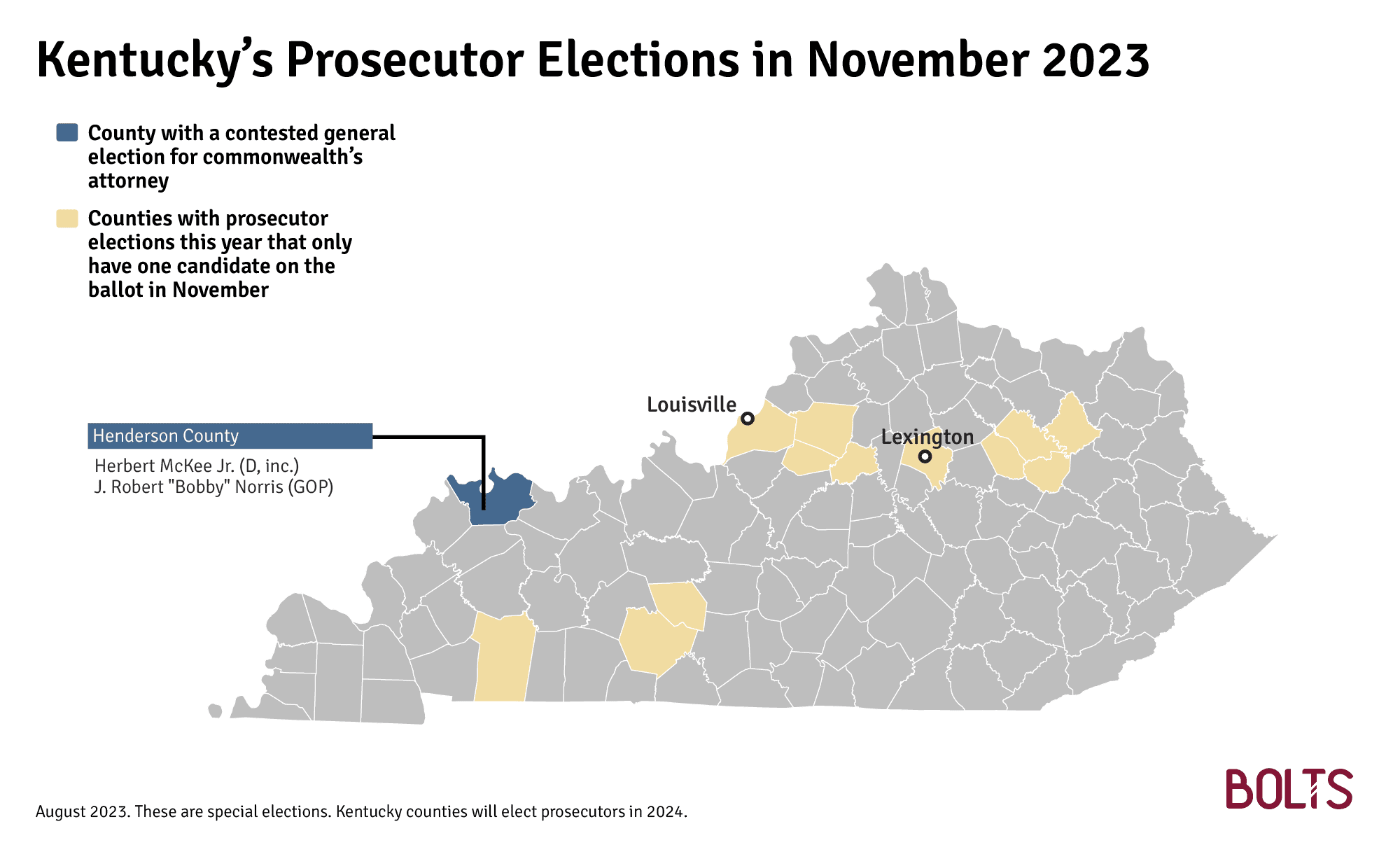

Kentucky has less to track this year: While there’s a strikingly large number of special elections, nearly all feature an unopposed incumbent. And Mississippi and Virginia have many uncontested races as well. Across the 123 elections in these three Southern states, only 24 will feature more than one candidate on November’s ballot.

Below is Bolts’ guide to the 2023 prosecutor elections in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Virginia.

Two other states are electing prosecutors this year (many more will in 2024). Check out Bolts’ earlier previews of races in New York and Pennsylvania.

Kentucky

The state wasn’t meant to select any of its commonwealth’s attorneys in 2023 but the two most populous counties each scheduled special elections due to unexpected vacancies. In the meantime, Democratic Governor Andy Beshear appointed prosecutors in each, Gerina Whethers in Jefferson County (Louisville), and Kimberly Baird in Fayette County (Lexington).

Whethers and Baird are now running to stay in their new offices and no one challenged them, ensuring they’ll easily win their first encounters with voters.

Appointed incumbents similarly face no challengers in four other circuits. Overall, this situation applies to counties that cover 1.5 million residents—roughly one third of the state’s population.

Only in Henderson County, a more sparsely populated county, is there a contested special election. It features two self-described conservatives: Democrat Herb McKee, who was chosen by Beshear to take over as commonwealth’s attorney when the longtime incumbent resigned last fall, faces Republican James “Bobby” Norris, an assistant prosecutor in his office.

All Kentucky counties are hosting regular elections next year.

Mississippi

DA Doug Evans retired in June, after spending decades subjecting a Black man named Curtis Flowers to six trials for the same crime, earning a rebuke from the Supreme Court, and facing mounting evidence that he targeted prospective Black jurors. Voters chose his successor in last week’s primary, and it’ll be Adam Hopper, Evans’ assistant who took over in court in the waning days of Flowers’ prosecution to urge a judge to keep him in jail.

Hopper, who’s running as a Republican, will face no opponent in November. Democratic DA Brenda Mitchell will also run unopposed in the Delta region after narrowly surviving a primary challenge against reform-aligned attorney Mike Carr.

In fact, 17 of 21 DA races in the state only feature one candidate on the general election ballot. Of the remaining races, three involve Democratic DAs with a reputation for defending some criminal justice reform.

Scott Colom, a Democratic DA in northeastern Mississippi who drew national press for ousting a notoriously tough-on-crime prosecutor in 2015, hoped to be a federal judge by now: President Biden appointed him to the bench in 2022, but one of the state’s GOP senators is blocking his nomination. In the meantime, Colom is running for reelection against Jase Dalrymple, a Republican who vows a “more conservative approach” to prosecution and says Colom is too quick to use diversion tools. Colom’s 16th District leans Democratic.

The other two Democratic incumbents who face challengers this fall are Jody Owens, the DA of Hinds County, and Shameca Collins, who represents a rural district south of Jackson. Owens and Collins each signed a letter last year pledging to not prosecute cases relating to abortion, and they’ve each touted their efforts to expand alternatives to incarceration.

In November, they’re running against independents Darla Palmer and Tim Cotton, respectively. The challengers have each indicated that their opponents are too focused on reforming the system. Palmer wants her campaign to send a message “that crime deserves punishment which includes incarceration,” she told Bolts this spring. Neither Palmer nor Cotton told Bolts whether they’d change the incumbent prosecutors’ approach to abortion.

The state’s fourth contested election, in the staunchly-red 14th District, is an open race that pits two assistant prosecutors, Republican Brandon Adams and Democrat Patrick Beasley.

Virginia

Eleven of Virginia’s commonwealth’s attorneys formed an alliance in 2020, called Virginia Progressive Prosecutors for Justice, meant to promote criminal justice reform. The group asked lawmakers to end mandatory minimum sentencing, abolish the death penalty, ban no-knock warrants, and increase opportunities for criminal record expungement, among other changes. And this year, most of these prosecutors had to stand for re-election.

Two alliance members, Arlington County’s Parisa Dehghani-Tafti and Fairfax County’s Steve Descano, went further than some of their colleagues in implementing changes like not charging marijuana without waiting for legislative change. They survived closely-watched Democratic primaries in June against opponents endorsed by local police unions. “If this election was a referendum on reform, our voters emphatically responded that they will not go backward,” Dehghani-Tafti told Bolts the night of her primary victory.

Neither Dehghani-Tafti nor Descano face another opponent in November.

But three Democrats who joined them in the statewide alliance in 2020 still stand for re-election in contested races this fall in populous Prince William, Loudoun, and Henrico counties.

In Loudoun County, Democrat Buta Biberaj faces Republican Bob Anderson, who served as the county’s prosecutor from 1996 to 2003. Biberaj announced earlier this year her office would not prosecute misdemeanor offenses like trespassing and petty larceny to prioritize violent offenses, a policy that Anderson has attacked as “unconscionable.” Loudoun voters have shifted massively to the left since Anderson’s tenure, from voting for George W. Bush for president by double-digits in 2000 to opting for Joe Biden by 25 percentage points in 2020, a year after Biberaj’s first election.

A similar debate is unfolding in Prince William County, where incumbent Amy Ashworth faces Republican Bob Lowery, who vows on his campaign site to “prosecute cases involving not just violent offenders, but all offenders.” Ashworth told Bolts, “As prosecutors, we have a duty to look at the bigger picture and attack the causes of crime to prevent it from occurring in the future, instead of blindly prosecuting all people to the fullest extent of the law.” In blue-leaning Henrico County, finally, Democrat Shannon Taylor faces Shannon Dillon, a former assistant prosecutor in the county who is echoing her fellow Republicans in saying the office “refuses to prosecute the criminals” and blames Taylor for antagonizing law enforcement

Besides those three traditionally partisan races, only one other county of more than 100,000 residents has a contested general election: Chesterfield County’s GOP incumbent Stacey Davenport faces independent Erin Barr, a former prosecutor who has focused her criticism of Davenport on a locally controversial decision to not prosecute a megachurch pastor for sexual solicitation.

Fifteen far smaller and often rural counties in Virginia also have contested prosecutor races.

Bolts reached out to non-incumbent candidates running in those counties to learn how they propose to change their county. Most who responded said they’d want to approach the office with a more independent spirit, or else emphasized a desire to ramp up sentences or foster closer relationships with the police. Running in Smyth County, for instance, independent candidate Paul Morrison said that people convicted of repeat offenses should be more likely to receive active jail sentences.

One exception was James Ellenson, running in Southampton County and Franklin City against longtime incumbent Eric Cooke. Ellenson emphasized his own credentials as a criminal defense attorney and said Cooke is “just way too tough.” But he didn’t answer follow-ups on specific practices he’d want to change.

Ellenson last year was the defense attorney of a six-year old child who shot a teacher at school, a case that drew attention to the fact that Virginia has no minimal age under which children can’t be criminally prosecuted.

What other elections to watch in the South

Plenty of other elections beyond prosecutorial races will shape the region’s criminal legal system this November. Kentucky’s governor’s race could unwind the state’s approach to rights restoration for people with felony convictions. Louisiana and Mississippi are electing nearly all of their sheriffs, the officials who run these states’ local jails.

And in Virginia, dozens of legislative races will decide whether Republicans win unified control of the state government; such a gain would strengthen Governor Glenn Youngkin and Attorney General Jason Miyares’ hand in their attacks against local officials who are pursuing reform policies. This will be the first general election in Virginia since Youngkin rescinded his predecessor’s policy of automatically restoring people’s voting rights when they leave prison.

Alex Burness contributed reporting.