California’s 10 Most Critical Elections for Criminal Justice and Policing

From Oakland to San Diego, Californians are deciding high-stake elections for sheriff, prosecutor, mayor, and judge.

Piper French, Daniel Nichanian | October 27, 2022

Against the backdrop of national conflicts over policing and crime, and repeat scandals affecting the state’s law enforcement agencies, California’s primaries already resolved many of the local races with big implications for criminal justice. Contra Costa County reelected its reform prosecutor, the scandal-ridden district attorney of Orange County easily held onto his seat, the DA of Santa Clara beat a progressive challenger—and, in a huge upset, Yesenia Sanchez ousted Alameda County Sheriff Gregory Ahern, whose long tenure saw a string of deaths in the local jail.

But plenty of elections were kicked into November runoffs. In Los Angeles County, home to a quarter of the state’s population, nearly every important race extended to the fall. And in San Francisco, the June recall of reform DA Chesa Boudin triggered a new election to replace him.

Will the scandal-tarred Los Angeles County sheriff, dubbed the “Trump of LA” by his critics, win a second term? Will progressives make gains on the Los Angeles city council, just weeks after a racism scandal forced one member to resign, or on the county’s judicial bench? Will reform prosecutors gain a new ally in Oakland? Will Sacramento ramp up policing against homeless people? Below is Bolts’s guide to the ten elections we are watching most closely in California—and some honorable mentions.

1. Alameda County district attorney

Nancy O’Malley, Alameda County’s longtime DA and a former president of California’s DA association, has been a vocal critic of many of the legislative reforms and ballot initiatives that progressives have championed to reduce incarceration. O’Malley is retiring this year, leaving deputy DA Terry Wiley, whom she has endorsed, to run against civil rights attorney Pamela Price, an outsider candidate and a strong critic of O’Malley’s failure to address racial disparities in the county’s justice system. “If you are a Black person in Alameda County, you are 20 times more likely to be incarcerated than a white person,” she told Bolts. “That’s an unacceptable, intolerable level of racial injustice that just called me to action.”

Wiley casts himself as sympathetic to reform, stressing his efforts to improve the juvenile justice system and reduce racial disparities from within. But he also presents himself as a moderate alternative to Price, which has won him the support of an array of law enforcement unions. Price is more squarely in the mold of progressives who have won DA offices elsewhere in the country: she has committed to never charging children as adults and centering restorative justice initiatives. Both candidates are also running in the shadow of horrible gun violence in Oakland. The winner will be the first Black DA in Alameda, a county of more than 1.6 million residents that encompasses the cities of Berkeley and Oakland.

2. Los Angeles County sheriff

Under Alex Villanueva’s leadership, the Los Angeles sheriff’s department has been marred by scandals and investigations into abuses and organized violence—enough to fill a book, Bolts reported in May. And the sheriff only drew more scrutiny since then as he ordered the search of the house of one of his chief critics in September.

In the runoff, Villanueva faces Robert Luna, who has accumulated his own controversies while heading the police department in Long Beach. The incumbent’s critics have still rallied around Luna, including Eric Strong, a more progressive challenger who was eliminated in June after coming in third. Whoever emerges victorious, local progressives have made it clear that they are circumspect about any talk of internal change given a history of failed reform, and they are pressing for more independent oversight: Angelenos are also deciding on Measure A, which would enable the county’s board of supervisors to remove a sheriff from office.

3. Los Angeles County judges

Progressive organizers in Los Angeles have crafted a relatively novel tactic this year: electing judges who want to reduce incarceration. Judicial elections are some of the most opaque and sparsely covered races in U.S. politics, but judges hold a great deal of discretion when it comes to bail, sentencing, and resolving cases without incarceration. Most judges are former prosecutors, and very few judges have backgrounds as public defenders; a recent study found that judges with public defense experience tend to avoid incarceration more frequently and hand down shorter sentences

Enter four candidates—three public defenders, and one civil rights attorney—who formed an informal slate, each running in a separate countywide race. Holly Hancock, Anna Slotky Reitano, Carolyn “Jiyoung” Park, and Elizabeth Lashley-Haynes all made it into the “Top 2” runoffs of their respective races in June. “We need judges that recognize and appreciate addiction programs, mental health programs, rehabilitation programs—we need judges that are going to implement restorative justice,” Lashley-Haynes told Bolts this spring.

4. Los Angeles mayor

Aided by over $80 million of his personal fortune, Rick Caruso, a billionaire mall developer and former Republican, burst onto the scene with a mayoral campaign centered on “cleaning up LA” and on responding to a rise in violent crime by strengthening the LAPD. Unusually for such a large city, Los Angeles has a “weak mayor” system, but the office still has a lot of power, and Caruso’s candidacy captured national attention as a test of Angelenos’ appetite for a law-and-order mayor. In June, Caruso came in behind U.S. Representative Karen Bass, a Democrat and a former physician assistant and community organizer who founded an influential community organization in South LA.

At first glance, it’d be hard to imagine two more opposite candidates. But Caruso has reinvented himself as a Democrat and talks up his support for reproductive freedom to win in this liberal city, despite past statements and donations. Bass, meanwhile, has veered to the right on issues of criminal justice and homelessness. She has distanced herself from progressive policies and politicians like DA George Gascón and has emphasized uncontroversial reforms like providing police officers with more training. The candidates’ relative convergence on these issues is captured by their joint support for 41.18, the controversial ordinance banning homeless encampments in wide swaths of the city; local housing advocates have criticized the ordinance for spurring constant displacement while doing nothing to actually solve homelessness.

Angelenos still have a sharp choice to make on homelessness and housing since their ballot also features Measure ULA, which would fund housing development and homelessness prevention efforts via a 4 percent tax on the sale of properties worth over $5 million, and a 5.5 percent tax for properties worth over $10 million. The measure, branded the “mansion tax,” is projected to raise between $600 million and $1.1 billion annually. It has the support of tenants rights organizations and homelessness advocates, but neither Bass nor Caruso have endorsed it.

5. Los Angeles city council

This powerful city council was left in tatters in early October after a tape leaked that featured three council members exchanging in a conversation filled with racist and cruel remarks. Council president Nury Martinez resigned in disgrace, while her colleague Kevin de Léon, whose term ends in 2024, appears determined to keep his job; the third councilmember, Gil Cedillo, already lost his re-election bid in June to abolitionist organizer Eunisses Hernandez.

Even before the scandal, Los Angeles was in the midst of a power vacuum, and several council races on the ballot this fall will further decide its upcoming politics.

In District 13, which covers most of the eastside neighborhoods Echo Park, Hollywood, and Silverlake, labor organizer Hugo Soto-Martinez is challenging incumbent Mitch O’Farrell. O’Farrell has supported the expansion of anti-camping policies across the city, advocated for increased police funding and presence in Hollywood, and attacked his opponent for supporting the reduction of police budgets Soto-Martinez, meanwhile, favors setting up more unarmed response teams and has taken aim at O’Farrell’s decision to clear a large homeless encampment from Echo Park Lake in March 2021, which led to mass arrests of protestors and journalists. O’Farrell’s office offered short-term housing and services in advance, but very few of the people living in the encampment still have housing, and several have died.

In District 11, which covers the city’s west side, councilmember Mike Bonin is retiring; he was one of the council’s few consistent votes against criminalizing homelessness. Though he has at times downplayed comparisons with Bonin, civil rights lawyer Erin Darling’s policies align most closely with the outgoing council member’s: he opposes 41.18, and wants to get police out of traffic stops and nonviolent disturbances. Darling’s opponent Traci Park has opposed Bonin’s efforts to create more housing for homeless people, even bringing a lawsuit against the conversion of a motel near her home. Park wants to increase police presence across the city—the Los Angeles Police Protective League called her “law enforcement’s choice.”

6. Los Angeles city controller

Ordinarily, this obscure and habitually misunderstood office would not warrant inclusion on such a list. But Kenneth Mejia, one of the two candidates in the Nov. 8 runoff, has brought a creative approach to his campaign, Bolts reported in July. He is proposing to use the office to increase transparency around the city’s finances and show residents just how much public money is being spent on policing–and what exactly that money is going toward.

Mejia put up a billboard that visualizes the size of the police budget. His campaign has put out data visualization tools that map LAPD traffic and pedestrian stops, and aggregate LAPD vendors in order to increase transparency. Mejia faces Paul Koretz, a city council member and former lawmaker who emphasizes a more traditional approach to the role focused on correcting government inefficiencies.

7. Los Angeles city attorney

A heated race for Los Angeles city attorney has become yet another exemplar of a debate playing out nationwide over whether to leave low-level offenses out of the criminal court system.

The office handles only misdemeanor cases; it also defends the city against lawsuits filed against it. Civil rights attorney Faisal Gill announced this summer that he would impose a 100-day pause on filing misdemeanor charges in order to evaluate whether to establish a more permanent ban on certain charges. (Bass, the mayoral candidate, eventually withdrew her endorsement of Gill after facing attacks over it by Caruso). Gill has also said he won’t enforce LA’s controversial anti-camping ordinance. His opponent Hydee Feldstein Soto has taken a very different approach, responding to Gill’s 100-day moratorium by saying, “You might as well take a bulletin board and say, ‘Bad guys from all over the world, please come to Los Angeles.”

8. Sacramento’s housing referendum, Measure O

Sacramento, like many California cities, has faced a sharp rise in people experiencing homelessness. Voters are now deciding whether to ramp up policing with a ballot measure that would outlaw camping on public property; the measure would also require that the city create new shelter spaces. The measure aims to comply with a court ruling that cities in California can only enforce anti-camping ordinances if they have shelter beds available. But local housing advocates say the support offered is inadequate.

They decry this push-pull dynamic of offering people shelter and criminalizing them for not having it, and they warn that it leads to an endless cycle between streets, shelters, and jail. “We keep funding police to do Band-Aid work instead of finding solutions,” Asantewaa Boykin, co-founder of a crisis response team that works with unhoused individuals, told Bolts. “I feel like I’m screaming at a wall.”

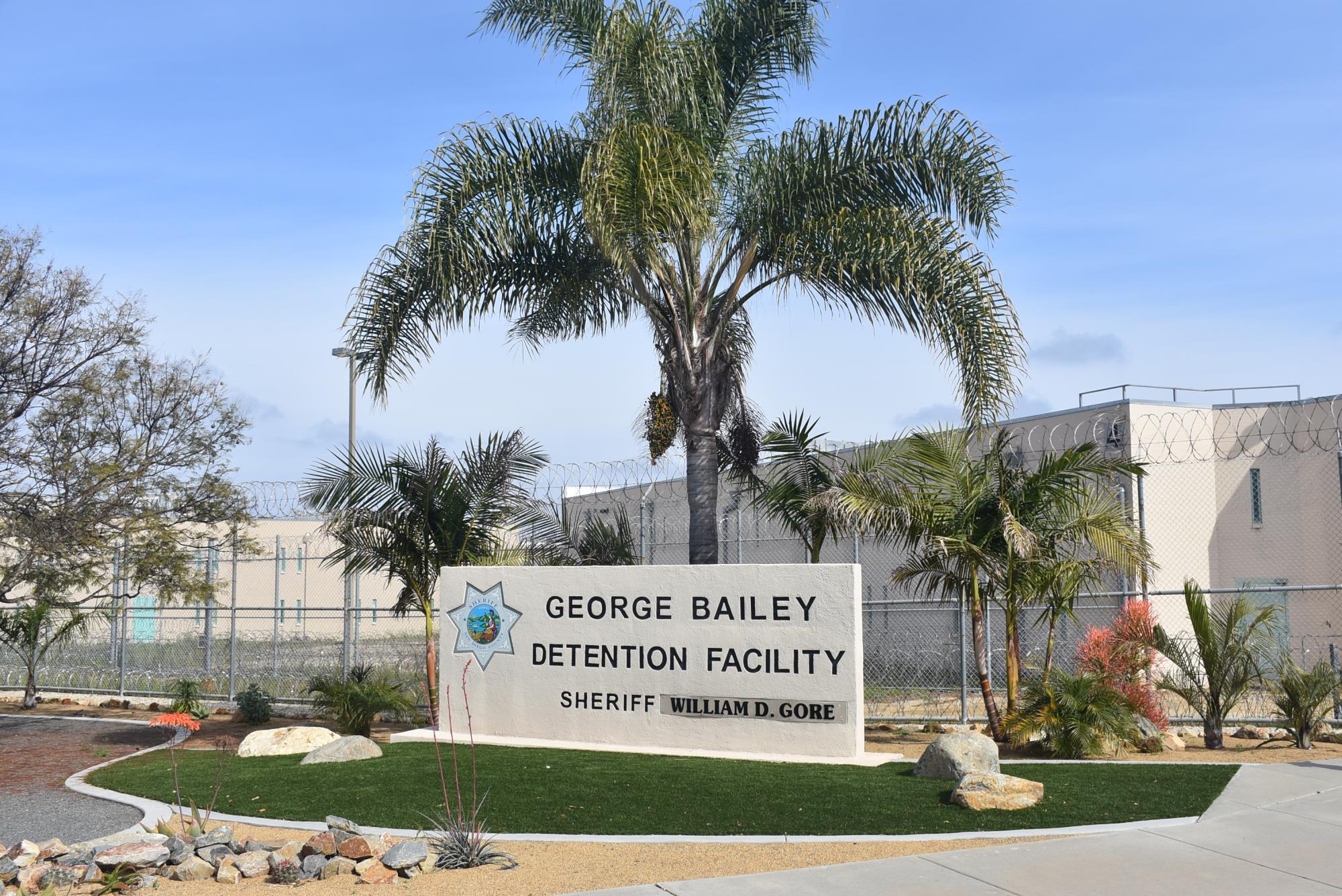

9. San Diego County sheriff

Home to California’s deadliest large jail system, San Diego has been hit by damning reports about the conditions that are contributing to this crisis. After the sheriff resigned earlier this year amid scandals, the jail’s dangerous conditions became an unusually prominent issue in the race to replace him. But even as the candidates talk about reducing deaths, Bolts reported in June that they bring vastly different commitments to the table.

The candidate who went furthest in proposing changes, Dave Myers, lost in the June primary; this paved the way for a Nov. 8 runoff between Undersheriff Kelly Martinez, who is endorsed by the association of deputy sheriffs, and John Hemmerling, a Republican who is generally critical of criminal justice reform.

10. San Francisco district attorney

Chesa Boudin, the prominent reform DA, was recalled in June after a campaign fueled by anger about growing homelessness and petty theft, propelled by opposition from the city’s powerful police union, and heavily funded by dark money. Mayor London Breed, a frequent critic of Boudin, appointed the recall surrogate Brooke Jenkins to serve as interim DA. The transition has brought a sea change to the DA’s office: the dismissal of 15 staffers, including a complete turnover at the unit that investigates police violence against civilians, and reversals of key Boudin policies, including his moratoriums on gang sentencing enhancements, on seeking cash bail, and on charging children as adults.

In the upcoming special election, Jenkins will defend her new seat against two challengers. The first is attorney Joe Alioto Veronese, a critic of both Boudin and Jenkins who is positioning himself as tough on crime and corruption. The progressive lane is occupied by John Hamasaki, the former police commissioner and critic of the San Francisco Police Department, who has lambasted Jenkins for her close relationship with London Breed and acceptance of large sums of money from the recall campaign.

Honorable mentions

Of California’s 58 counties, only three have contested DA runoffs in November—Alameda and San Francisco (see above), as well as Imperial, on the state’s southern border—and seven have contested runoffs for sheriff. (See Bolts‘s full list of candidates who ran for DA and sheriff this year across the state.)

In such an immense state, many other local elections will shape criminal justice policy.

In Long Beach, just south of Los Angeles, policing has been a major faultline in a mayoral race between two council members. The Long Beach Police Officers Association, which is supporting Suzie Price, has attacked Rex Richardson for his past support for reducing the police budget in favor of community alternatives; progressives are criticizing Price for opposing a fund to defend undocumented immigrants. But Long Beach has a ‘weak mayor’ system, and a council-appointed city manager enjoys a lot of power—including appointing the police chief.

Oakland voters will also elect a new mayor. With ranked-choice voting, they will decide which of ten candidates will replace outgoing mayor Libby Schaaf, who has consistently supported expanding the budget of the Oakland Police Department, which has been under federal oversight for years.

And an election for one of the five seats on the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors could either shore up the board’s progressive majority or dissolve it. This is the body responsible for deciding the county budget, which includes funding for the sheriff department and for mental health or youth programs. Incumbent Sheila Kuehl, who is termed out, is a critic of Villanueva and she has been a champion of the county’s “Care First, Jails Last” policy, which aims to fund alternatives to incarceration. Running to replace her are West Hollywood city council member Lindsey Horvath, who recently helped secure a reduction of the number of sheriff’s deputies contracted to patrol West Hollywood in favor of unarmed community response teams, and state Senator Bob Hertzberg, a moderate endorsed by the association of L.A. Deputy Sheriffs.

But suspense in one election that was once seen as a potential barnburner has deflated.

Rob Bonta’s bid for a full term as attorney general was dubbed by Politico in the spring as the major bellwether for the public’s appetite for criminal justice reform. But Bonta, who has a long record as a reform-friendly politician that he has cultivated since becoming attorney general in 2021, received 55 percent of the vote. That’s roughly on par with the Democrats running statewide for governor or lieutenant governor. Independent candidate Anne Marie Schubert, a DA who gained national attention for pressing the case against criminal justice reforms, came in fourth with 8 percent and was eliminated from the runoff. Bonta now faces Republican Nathan Hochman, who also staunchly opposes the reforms pursued in the state. Governor Gavin Newsom, who appointed Bonta last year and is running for a second term, has also enjoyed significant leads in the governor’s race.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the county that the city of Richmond in in.