On Solitary Confinement, California Officials Side With the Prison System—Again

Organizers wanted to ban the use of solitary confinement against pregnant Californians. They got something else entirely.

| November 19, 2024

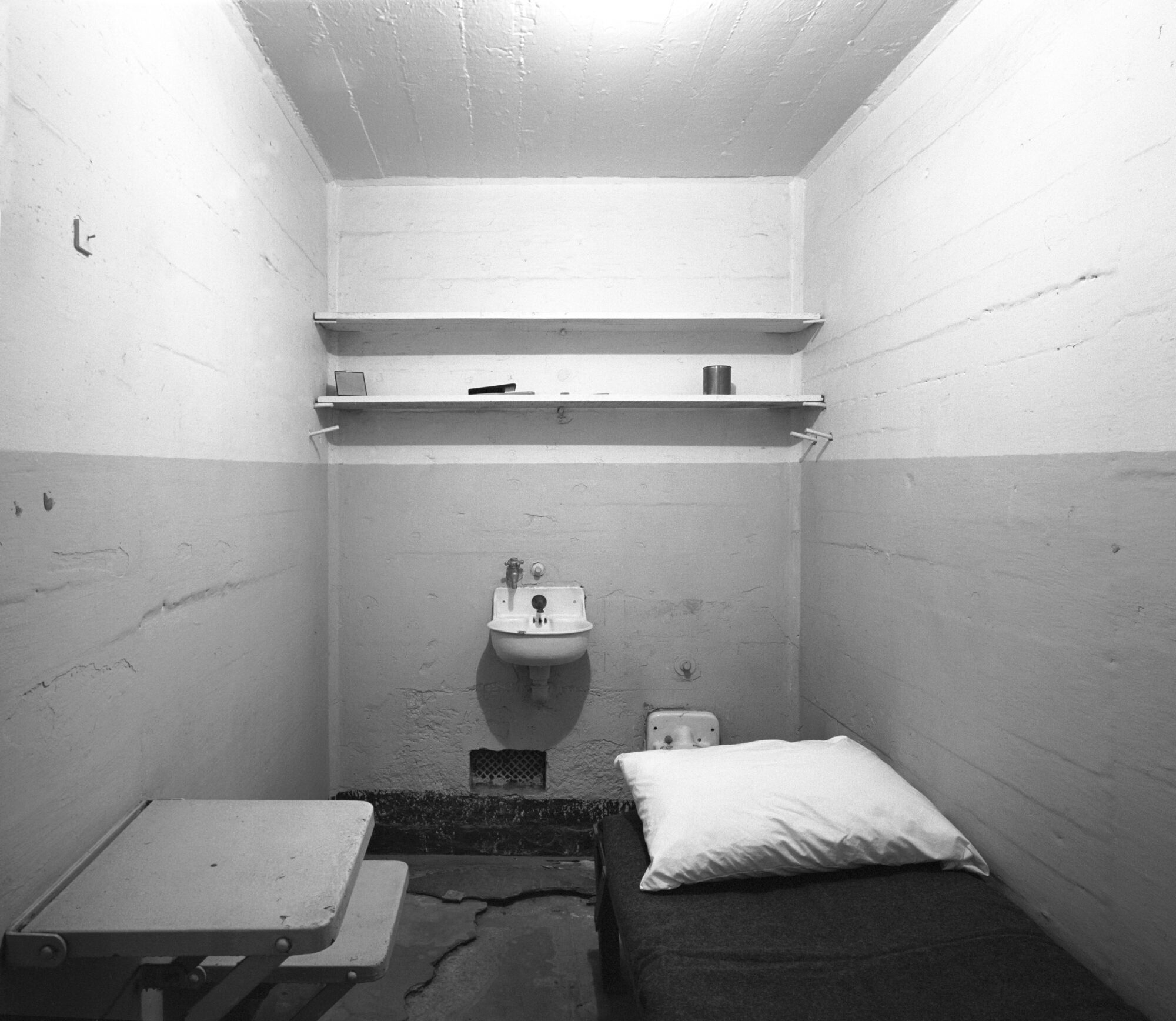

Cynthia Mendoza’s first pregnancy, in the free world, was a time of enveloping love and anticipation. But in 2006, six months into her second pregnancy, Mendoza was arrested and jailed pre-trial in a Lynwood facility overseen by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Once there, she was sent to solitary confinement, where every good thing she remembered about pregnancy became a horror. “I had nobody to talk to, I had nobody to comfort me,” she told me. Cut off from human contact and the warmth of the sun, Mendoza’s mental health quickly deteriorated. Her access to proper nutrition was so poor that her hair started falling out.

Mendoza gave birth shackled to a hospital bed, and she only got to spend three days with her newborn son. On the third day, jail officials handed him off to her father. Then, already suffering from postpartum depression, she was sent back to solitary confinement. “It felt like I was just stuck in this black cloud, and I could not see a foot in front of me,” she said. She would remain there for nearly three more years—all while she was still innocent in the eyes of the law.

Some 16 years later, in 2022, a broad coalition of organizers in California introduced an ambitious bill to limit the use of solitary confinement in the state’s prisons, jails, and detention centers—and outlaw it entirely for pregnant people, as well as a few other categories of vulnerable individuals. They called it the Mandela Act after the South African leader, who was held in solitary confinement for at least six of the 27 years he spent jailed. “Solitary confinement, if done a certain way, drift[s] into the area of torture—and these are correctional facilities, not torture camps,” California Assembly Member Chris Holden, the bill’s sponsor, told me.

Mendoza watched the bill’s progress with excitement. If it passed, she thought, no one else would have to go through what she did. No other children would have to grow up, like her son had, grappling with the realization that the time they spent in their mother’s womb had been, for her, a time of total deprivation and isolation.

In 2022, the Mandela Act was passed by the state legislature, but California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed it. In 2023, organizers negotiated with the governor’s office to try to come up with a compromise of the Mandela Act that he would consider signing into law. Then, this year, a different organization picked up the Mandela Act’s provision banning solitary for pregnant people and included it in a separate bill focused on improving nutritional standards for pregnant and postpartum women in custody.

While the Mandela Act stayed stuck this year, this new, narrower bill was adopted by lawmakers in August and signed into law by Newsom in September. But by then, it had grown so unrecognizable to its original community sponsor that they withdrew their endorsement.

The initial bill would have banned solitary confinement for anyone who is pregnant in a California jail, detention facility, or state prison. The version that became law no longer applies to local jails and detention centers, meaning that someone like Mendoza wouldn’t be covered.

And instead of outright banning solitary confinement, it capped the number of days it can be used. But the result is that the new law expressly allows prison officials to put pregnant women in isolation for up to five days at a time in certain cases. Advocates are alarmed that, for the first time, the legislation has codified in California law that it is permissible to use solitary confinement against pregnant women.

The divergent fate of the two bills is a tidy illustration of what can happen to grassroots efforts to change criminal legal policy in the face of two powerful forces: the California prison system, which enjoys great influence over the state’s elected leaders and tends to resist efforts to impose limits on its authority; and Newsom, whose efforts to style himself as a national leader on prison reform have often involved letting that system guide how and when it wants to change.

Keramet Reiter, a law professor at UC Irvine who wrote a book on the rise of solitary confinement in California, was frank in her assessment of the new law. “This is an abomination,” she told me. “There are categories of people who unequivocally never, ever should be in solitary confinement, and one of them is pregnant women.”

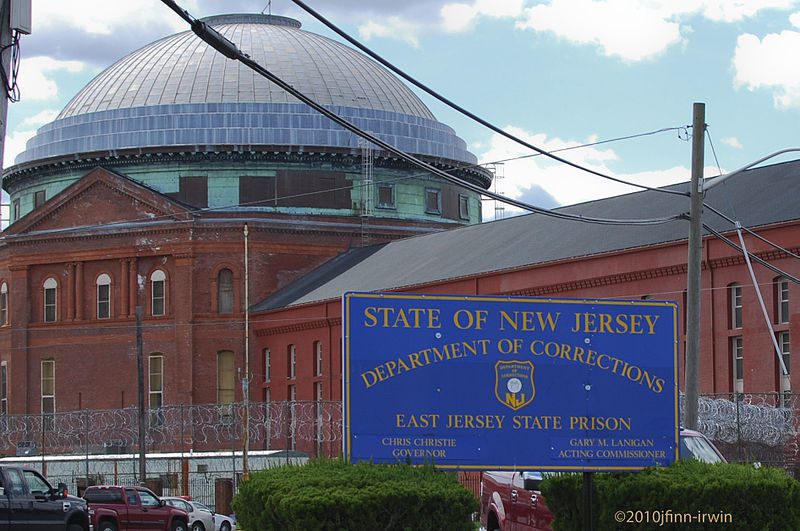

The debate over solitary confinement in California has been a multi-decade battle between the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) on one side, and the prisoners it puts in solitary confinement on the other, alongside survivors of the practice and their family members and supporters. In 2013, a historic prisoner hunger strike organized by four men in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay led to a lawsuit and eventual settlement, Ashker v. Governor of California, that was meant to lead to significant changes, including an end to the practice of indefinite isolation, which left people languishing in solitary for years on end with little recourse.

But in 2022, when Holden introduced the Mandela Act, he told me that the bill was partially a response to CDCR’s failure to abide by the reforms laid out in Ashker. “CDCR, you have been told by the courts to change how this solitary confinement process works and how it’s being utilized—and to no avail. So we write a bill to say, ‘Okay, we’re just asking you to do what the courts ask you to do,’” he said.

In California, 10 percent of all state employees work in corrections, and their union, CCPOA, has a great deal of lobbying power in Sacramento. The association regularly flexes its muscle via political donations, but its spending on Newsom has been especially notable: the union sunk $1 million into TV ads promoting his gubernatorial run in 2018, and they have more recently spent $1.75 million opposing the recall effort and $1 million on Proposition 1, Newsom’s marquee mental health treatment plan. The latter two expenditures alone represent nearly a third of all CCPOA’s political donations since 2001, according to a recent Cal Matters analysis.

Newsom has championed some aspects of prison reform during his nearly six years as governor, moving to shut down some facilities and placing a moratorium on the state’s use of the death penalty. But he has also overseen raises and perks for prison guards that even California’s office of legislative analysis found unwarranted. And after the same office determined that five more prisons could be shut down, Newsom declined to implement further closures. (The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment for this story).

Solitary confinement has remained a cornerstone of prison officials’ strategy for managing incarcerated populations, as they insist that they need to be able to continue to separate people from the general population for safety reasons. And Newsom has repeatedly erred on the side of trusting CDCR’s discretion and allowing the agency leeway to shape its own policy on this issue. (The CCPOA officially opposes the Mandela Act.)

Reiter, however, contends that it’s not an all-or-nothing decision. “Certainly people get in situations in prison where they need to be removed from the rest of the population, but there are ways to do that without restricting their access to natural light, to human contact, to time out of their cell,” she told me. To Reiter, Newsom’s willingness to let CDCR guide its reforms casts doubt on his stated commitment to changing the state’s carceral system. “It raises real questions to me when a governor who claims to be so invested in reform defers again and again in these ways,” she said.

In 2022, after the Mandela Act made it to the governor’s desk, Newsom returned it unsigned. In his veto message, the governor called the bill “overly broad.” He granted that solitary confinement in California was “ripe for reform,” but chose to put the prison system in charge of overseeing that reform, directing CDCR to implement changes to its solitary confinement policies.

The department waited nearly a full year to do so, until the Mandela Act was once again being debated and nearing the final deadline for Newsom to sign or veto bills. Then, it proposed its own policy changes that would reduce the number of offenses that land someone in solitary and raise the number of hours of mandatory out-of-cell time to 20 per week, meaning that someone in solitary confinement could still be held in their cell for more than 21 hours per day.

At the same time, Newsom’s office was seeking to winnow the Mandela Act into a data collection bill that outlawed solitary only for pregnant women. The Mandela coalition refused these changes, considering them an unacceptable compromise that would allow Newsom to tout a seemingly progressive reform while failing to address the structural problems with prison isolation. Instead, they opted to pause on the legislation in order to keep negotiating with the governor the following year. They already had all the votes they needed in the state Assembly to get it back on Newsom’s desk: “We were simply parked right outside the governor’s door,” coalition member Hamid Yazdan Panah, co-executive director at Immigrant Defense Advocates, told me.

But come 2024, Newsom wouldn’t engage. The coalition tried to negotiate, but they didn’t get far. In late July, a staffer from the governor’s office emailed the coalition to let them know the door was closed, referencing the recent CDCR changes as justification. “Given CDCR’s relatively recent update to their regulations on the use of [solitary] the [Governor’s office] isn’t comfortable making further changes to [solitary] policy this year,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, organizers with the gender justice organization Essie Justice Center, based in LA and Oakland, were trying to advance separate legislation that would improve the treatment of pregnant people in custody. As initially conceived, Assembly Bill 2527 included a blanket ban on solitary confinement for pregnant women in jails, detention facilities, and prisons across the state.

Assembly Member Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, the bill’s legislative sponsor, had also supported the Mandela Act, but she told Politico that she wanted to ensure these sorts of protections regardless of whether Mandela made it through. But the bill’s focus on pregnant people happened to resemble the narrowed version of the Mandela Act that Newsom’s office pushed in 2023. “Internally within Sacramento or in the capital, I think this bill was pitted against the California Mandela Act,” Essie policy associate Ellie Virrueta Ortiz told me. Virrueta Ortiz believes that legislators and the governor’s office “wanted this to be the smaller, narrower, much more palatable version.”

This summer, as they worked on drafting the bill, Bauer-Kahan’s office called together policy representatives from Essie as well as CDCR. The prison officials were pushing for an exception to the blanket ban: If the move was for their own protection, pregnant women could still be housed in solitary confinement for up to 10 days at a time.

When I reached out to CDCR asking why they would advocate for this sort of exception, the department’s press secretary responded: “By moving the person from their housing (often a dormitory environment) to a more protective area, CDCR is allowed a window to determine a safe housing alternative. The bill also includes provisions for CDCR works to ensure the pregnant person is allowed to remain enrolled in their programs.”

Essie’s representatives pushed back. The group’s executive director, Gina Clayton-Johnson, told me that their group wasn’t opposed to amending the legislation, but the exception that CDCR was asking for was a bridge too far.

“No amount of solitary confinement of a person while they’re pregnant is ever fine,” she said.

Soon after, Bauer-Kahan’s staff informed Essie that they had accepted a version of CDCR’s request: The bill was being amended to allow up to two days of restrictive housing at a time for pregnant people. A subsequent draft of the bill raised the time limit from two to five days. Bauer-Kahan’s office didn’t respond to my request for comment.

When Essie’s members saw the new draft that had been submitted to the Senate Appropriations Committee, they learned that it no longer applied to pregnant women held in jail or immigration detention facilities.

For Essie, this news was a gut punch. “It was something that really, truly was last minute and was unexpected,” Virrueta Ortiz told me. “We know that the real problem is in the jails.”

Vanessa Ramos, a community organizer with Disability Rights California and a survivor of solitary herself, didn’t mince her words: “The California legislature is viciously and violently co-opting bills from the community, encouraging folks to take obnoxious amendments that not only water down the bill, they create a false narrative that the California legislature is working with CDCR and county jails, to improve conditions—and they’re not,” she told me.

When organizers with Essie reached out to the coalition supporting the Mandela Act to ask their advice, a member offered language that would enshrine the sort of provisions Reiter outlined: safe isolation that still allowed out of cell time and proper medical care. Bauer-Kahan’s office didn’t accept these amendments.

Finally, Essie made the difficult decision to withdraw their support for the bill. “So many human rights groups had really called us and said, ‘This is not something that we want to see in the state,’ and we really had to listen to that,” Clayton-Johnson said. Over 80 organizations sent a letter to Bauer-Kahan and Newsom expressing their opposition. They urged the governor to veto the bill. A day of action that was originally intended to galvanize supporters of the Mandela Act but became a protest against AB 2527 instead, where Mendoza spoke about her experience in solitary. “It was the most degrading, inhumane thing that I’ve ever gone through,” she told the crowd, her voice shaking.

But it was too late. The bill breezed through both chambers. “No one paid attention to it, because everyone thought it was the same bill as before,” Yazdan Panah said. On Sept. 27, Newsom signed it into law, leaving the coalition outraged that California had explicitly enshrined into its statutes the use of solitary confinement for pregnant women.

This development “follows a decades-long pattern of nominal reform in this state where the prison system in particular gets just one millimeter ahead of the bare minimum with their policies,” Reiter said. “It feels like reforms that are calculated to avoid actual reforms.”

For now, the fate of the Mandela Act is uncertain, but organizers vow to continue the fight. Ramos credited the veterans of the fight to end solitary confinement in California for refusing to give in to efforts to water down the bill. “The Mandela Act could have very easily been passed, but the receiving end would have been some fucked up bill,” she said. “The Mandela Act has not passed because of the integrity of the people that are leading these efforts.”

“I don’t see the movement slowing down,” Reiter said. She outlined a number of positive changes that have occurred since the days of the 2013 hunger strike: vastly more public attention on the harms of solitary, policy changes that have ended indeterminate confinement. “But are we still overusing solitary confinement? Is the ultimate winner still the Department of Corrections, who’s shown again and again that they’ll set the policies and the terms and that they control the elected politicians?” she said. “So we have a long way to go.”

Holden, the Mandela Act’s sponsor, is termed out of the state legislature this year. I asked him for his reflections on the bill’s future after three unsuccessful legislative sessions and whether he believes that CDCR can reform solitary confinement by itself.

“If there’s a system that’s working for some, they don’t think that it really needs to be modified to any great extent, then they’re not going to necessarily have the motivation to see that extended change happen,” Holden said. He also noted that CDCR still has never fully complied with the Ashker settlement requiring extensive changes to the state’s use of solitary confinement—and, as of this January, the settlement is now closed. “I think that CDCR is now able to operate in a lane of making the changes that they see appropriate to make, unless directed by the legislature to do something different,” he said. “And that time has not yet come.”

Cynthia Mendoza’s son is 18 now, but the conditions of his birth linger. “It definitely has affected him,” she told me. He has a hard time talking about it, she said, but lately, “we have been working on his feelings and what he went through, having to be born in jail, and then having to visit his mom in prison.”

It remains a tough subject for Mendoza as well, but she told me that she will continue to speak out about her experience despite the difficulty of revisiting the worst moments of her life. “I will never lose hope that my story can help change the narrative for other women,” she said.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.