After Reforms to Solitary Confinement, Massachusetts Prisoners Say Officials Just Renamed It

The state passed a law curtailing restrictive housing in 2018, but people in prolonged isolation say the practice continues and are now pushing for new reforms.

Victoria Law | March 29, 2024

Massachusetts prison officials put Elosko Brown in isolated housing in 2020 after accusing him of participating in an altercation with guards that January at the Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center, the state’s maximum-security prison for men. Brown, who disputes the charge, says prison officials had different names for the units they put him in—the Department Disciplinary Unit (DDU) at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution in Cedar Junction, where he lived until 2021, and the Secure Adjustment Unit (SAU) at Souza, where he’s currently incarcerated and remains in isolation four years later.

But whatever the names, Brown and other people incarcerated in these units say they only replicated the punitive solitary conditions that triggered state reforms several years ago, evading the reforms’ goal to reduce prolonged isolation in the Massachusetts prison system. Over the past year, Brown and others incarcerated in state prisons who say they suffer from long-term isolation have gone to great lengths to protest their conditions and advocate lawmakers for reforms—from launching a hunger strike last October to testifying remotely before a legislative committee in January.

“Can you imagine being secluded in a tight space that’s the size of some of your bathrooms?” Brown and nine other hunger strikers described in a letter pleading with the attorney general to investigate SAU conditions. “The Secure Adjustment Unit was put in place in an effort to end solitary confinement, but has mirrored the same conditions as those previous restrictive housing units.”

People who remain isolated in Massachusetts prisons argue that officials are violating provisions of the Criminal Justice Reform Act, a law the state adopted in 2018 that limited solitary confinement, known as restrictive housing within the state’s prison system. The law limited placement in restrictive housing to no more than six months and prohibited it for anyone with a release date of fewer than 120 days unless that person “poses a substantial and immediate threat.”

The 2018 law also required that jails and prisons report the number of people in restrictive housing and offer them programming, showers three times a week, and access to phone calls and visits.

Officially speaking, nobody remains in solitary confinement in Massachusetts prisons. That’s because, in response to the 2018 reforms, the Massachusetts Department of Correction created new units, such as the Behavioral Adjustment Units (BAUs) and Secure Adjustment Units (SAUs), to replace restrictive housing for people who threaten security or orderly operations within prisons. (The DDU and the prison in Cedar Junction closed in 2023.)

In December 2018, Massachusetts state prisons held 392 people in restrictive housing. It was not until 2020 that the state consistently held fewer than 300 people in restrictive housing and not until the end of June 2023 that the state phased out all of its restrictive housing units.

But as of mid-February, the BAUs and SAUs isolated roughly the same number of people, over 270, as had been in restrictive housing in January 2020. The Behavioral Assessment Units had 157 people; 18 had been there for more than 90 days. The Secure Adjustment Units confined 120 people, 72 of whom had been there for more than 90 days.

In response to questions for this story, a Massachusetts Department of Correction spokesperson told Bolts the agency followed the mandate of the 2018 reforms by implementing “a strategic initiative to eliminate restrictive housing, close its disciplinary unit, and stand up new adjustment units that deliver personalized programming plans.”

While the BAU was meant to temporarily isolate those who pose a possible safety risk, prison officials define the SAU as “a highly structured unit that is not Restrictive Housing which provides access to cognitive behavioral treatment, leisure time activities, and mental health services for those inmates assessed as needing a specific structured program intervention to support positive adjustment.”

People who remain in long-term isolation and lawmakers who want to reduce solitary claim that lockups have simply renamed the practice.

“What’s clear is that the Department of Corrections is not following the spirit of the law, they just changed the acronyms,” state Representative Erika Uyterhoeven, who toured the SAU this past January, told Bolts.

Uyterhoeven and other Massachusetts lawmakers are again trying to pass legislation restricting solitary confinement in the state. Last year they introduced a bill to ensure at least eight hours of out-of-cell time without restraints for people incarcerated throughout the state. The bill also seeks to expand visits and access to vocational and educational programming. If passed, this would affect everyone behind bars: state prison data shows that in 2023, only one-third of people in Massachusetts prisons were enrolled in any type of prison programs and over 90 percent were on wait lists.

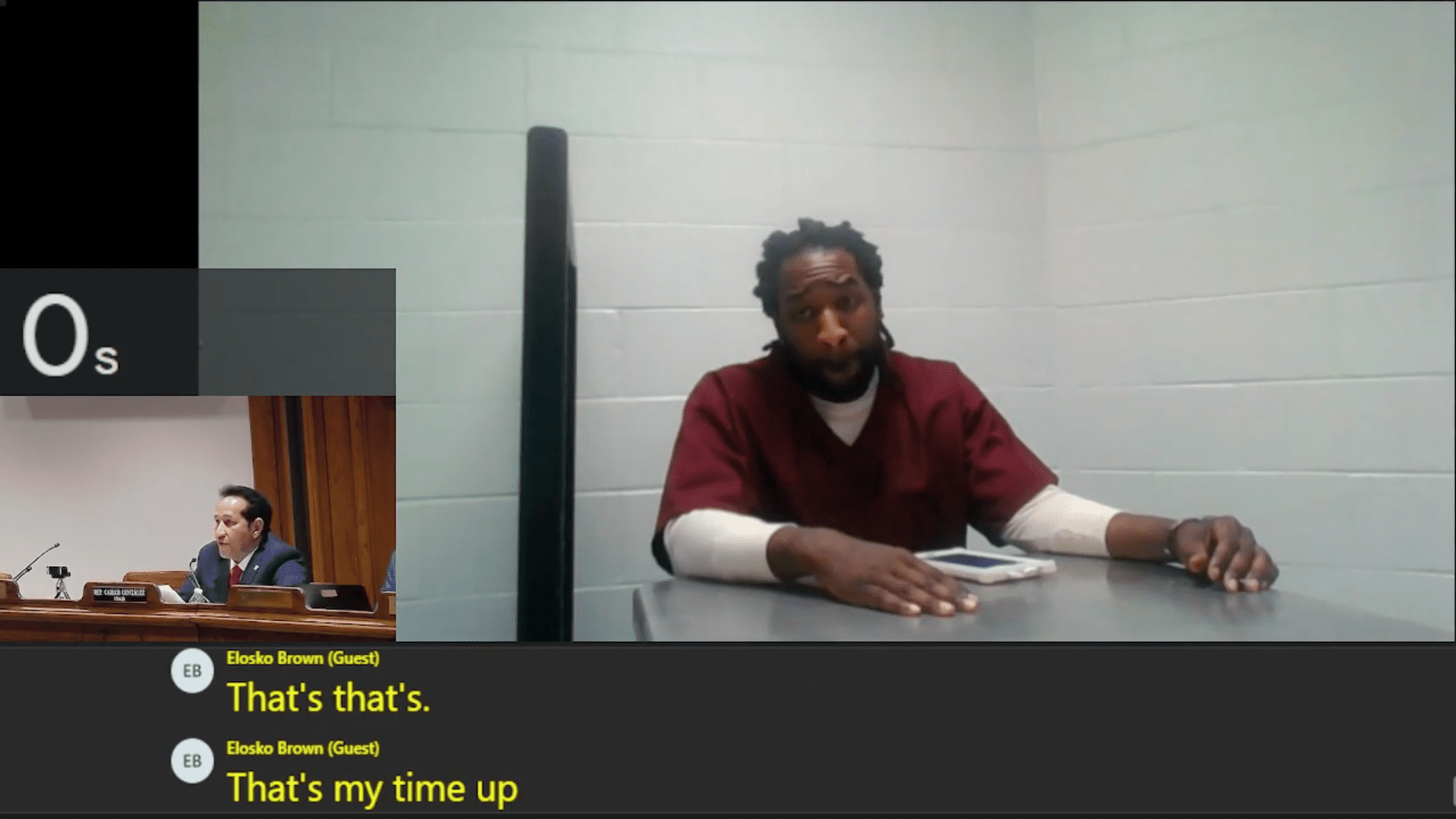

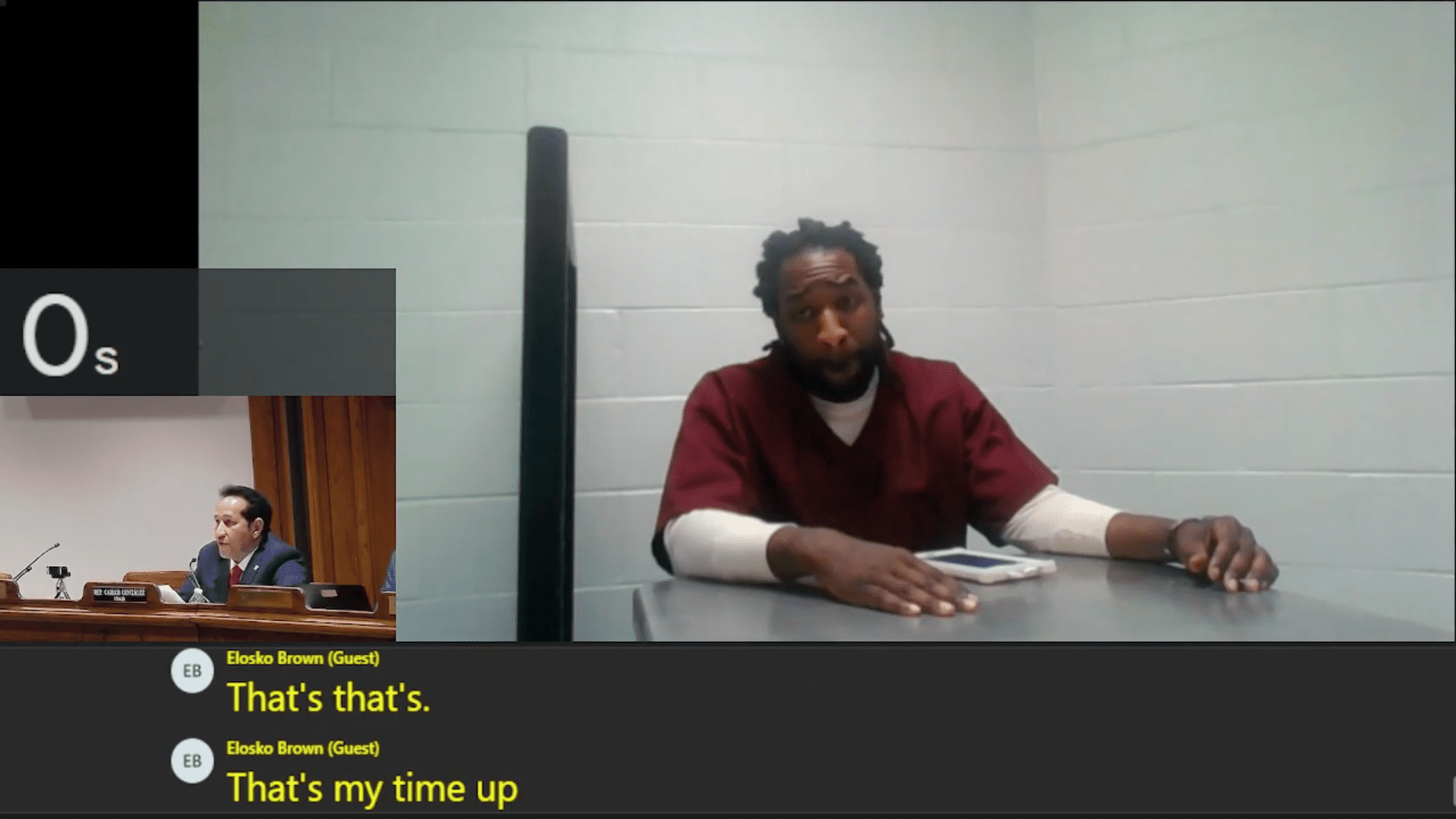

The bill languished without action in the Joint Committee on Public safety and Homeland Security for a year until this past January, when the committee finally held a public hearing on it. Nearly 30 people incarcerated inside Massachusetts prisons, including Brown, signed up to testify at the Jan. 23 hearing via video conferencing—marking the first time that the committee ever heard testimony directly from incarcerated constituents.

During his allotted three minutes before the committee, Brown described not being allowed access to programs or even phone calls—which are now free for people in Massachusetts prisons. Instead, he says he is left with a sense of “repetitive meaninglessness.”

“I wake when they wake me, I eat when they decide to feed me, [and] the day ends when they say it does,” he said.

Dominic Rezendes also spoke to lawmakers from inside the SAU during January’s committee hearing. The 34-year-old has spent the past 13 years in prison and is slated for release within the next year and a half. But, he told lawmakers, in the SAU, he has been unable to access reentry services or programs despite asking on a near-daily basis. “I have never had a license or apartment,” he testified. “I have nothing but a brand-new start.”

“The only way to describe this experience is ‘mentally deteriorating,’ (understatement!)” Rezendes wrote in a message to Bolts. “Being sent to SAU has been hands down the most mentally destressing and overall worst part of my 13 years locked down.”

According to department policy, Massachusetts prison staff and treatment providers are supposed to develop a plan to release someone from solitary conditions whenever they’re sent to an isolated housing unit. Under that policy, officials should make a written progress review for people in solitary housing every 90 days, but several people told Bolts those reviews rarely happen.

“It’s one thing to be in segregation and be reviewed to see if you still pose a threat,” said Bonnie Tenneriello, who has litigated numerous solitary confinement cases as staff attorney at Prisoners Legal Services of Massachusetts. “It’s another to be in a unit with severe deprivations and be told, ‘This is your housing placement.’”

Each 90-day placement review requires three staff members—a guard, a program officer, and a mental health clinician—thus requiring overtime from existing staff. This poses major demands on the prison system, when the Department of Correction stated in a February court filing that it had a shortage of 744 guards and program officers and an unspecified shortage of mental health staff.

Even then, people say they go much longer than three months without review. Over the past two years in solitary housing, Brown says he received one progress review—and only after he and other men repeatedly inquired about them.

“These reviews are designed to be a sham,” he told Bolts. “It seems their only interest is what a person has done in the past.”

By October 2023, Brown had had enough and embarked upon a hunger strike, joined by at least 18 other men in the SAU. In their letter to state Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell that month, the hunger strikers demanded that the office investigate their living conditions, a demand echoed by both advocacy organizations and lawmakers. In a separate letter to the attorney general, Brown accused prison officials of sweeping both the hunger strike and SAU conditions “under the rug” and stated that nothing has changed despite their protest.

At least he was able to testify. Jensen Peraza-Rivera, who was placed in the BAU in August 2022 and assigned to the SAU in March 2023, said that he would have signed up had he known about the hearing and that incarcerated people could testify via video. Peraza-Rivera’s description of his conditions illustrate the extreme isolation: He’s allowed two and a half hours outside his cell each day, 90 minutes of which is outdoor recreation alone in a large cage and an hour inside, seated with one arm handcuffed to a table and both legs restrained. Sometimes another person is restrained across from him at the same table; occasionally, they might even be given a chess set with missing pieces. Sometimes, all the men can do is talk to each other or shout to the handful of men shackled to the other tables for an hour.

Even then, Peraza-Rivera said few men choose to undergo the required strip search before and after each recreation period simply to sit restrained at a table. He himself has not gone to indoor recreation for a year, he told Bolts. No staff has ever told him what steps he needs to take to be released from the SAU and, he says, they often skip his cell when taking people to the programs that are offered.

Jesse White, policy director with Prisoners Legal Services of Massachusetts, said that the organization collaborated with other prison advocacy groups to do outreach inside Massachusetts prisons ahead of the legislative hearing in January. Eighty people throughout the prison system expressed interest in testifying. After the committee limited testimony from prisons to 90 minutes total, the group asked incarcerated people to collaborate and choose spokespeople to deliver testimony.

Even then, not everyone was able to speak. Champree Dinkins, who was incarcerated in the BAU inside the state’s only women’s prison at Framingham, says she put in a request to testify at the hearing, but never received a response. On the day of the hearing, prison officials told Prisoners Legal Services that Dinkins, as well as a man in another prison, would not be allowed to testify because of their placement in the BAU.

Dinkins told Bolts that she “suffered from deep anxiety” during her 30 days inside the prison’s BAU, saying she was allowed outside her cell three hours a day—90 minutes indoors to watch television or play cards, and another 90 minutes outside in a cage. She says that many days she had to choose between going outside or eating breakfast, saying prison staff would throw out her meal by the time she got back from rec. Now in the SAU, Dinkins says she’s allowed two more hours of out-of-cell time, five hours total, but says she still cannot participate in educational programs.

“I have one semester left of Babson [College] and I haven’t been given the opportunity to finish from the SAU,” she wrote in a message to Bolts.

The inability to testify wasn’t the only barrier to publicizing conditions that some people inside faced. Bolts also had difficulties corresponding with people in isolated housing. The Massachusetts prison system contracts with CorrLinks to provide electronic messaging. But Brown and others in SAU who testified at the January committee hearing say they never received numerous messages with questions for this story.

After over a month of silence from Rezendes, Bolts learned that, in a fit of desperation, he had set a fire in cell in early February and was placed on mental health watch, where he had no access to his tablet to send or receive electronic messages. CorrLinks automatically deletes messages after 30 days, whether they have been read or not. By the time Rezendes was returned to the SAU and allowed access to CorrLinks, Bolts’ many follow-up messages had been erased.

Tenneriello notes that people confined to higher security units have fewer opportunities to participate in educational, rehabilitative or therapeutic programs. But in prison, the inability to participate in programs translates to not earning time off one’s prison sentence. It can also negatively impact chances at parole. “It also means that they’re not being prepared to succeed when they get out,” she added, setting them up for a higher risk of recidivism. “The whole system is a vicious cycle. This legislation aims to reverse that vicious cycle and help people get out and stay out successfully.”

Rezendes echoed the need for more programming in his testimony to the legislative committee in January, urging lawmakers to pass the bill and telling them, “When you give people the resources and access to do better, they usually will.”

The bill to expand programming and out-of-cell time for all people incarcerated in Massachusetts is still sitting in the same committee where it’s been stalled for a year; lawmakers took no action after February’s hearing. The committee, which is chaired this year by Democratic Senator Walter Timilty and Representative Carlos González, both of whom are Democrats, has until April 8 to vote on the bill, which would then still have a long voyage to pass through both chambers. The legislative session ends on July 31.

The solitary reforms, which would also apply to jails, face sharp criticism from sheriffs who run local lockups. Carrie Hill of the Massachusetts Sheriffs’ Association testified that, while the association supports the bill “in theory,” she stressed that it remained “crucial that the sheriffs’ office have flexibility [for programming requirements]” and that “eight hours may not be the best for the safety and security of the institution.”

Uyterhoeven, a co-sponsor of the House bill, refutes that assertion. “It’s not actually about security,” she said. “Is putting someone in a deeply traumatizing environment really going to help them when they are released? There are other ways that we could be helping address those underlying issues that led to why they were punished in the first place. But we’re not addressing any of that by throwing people in solitary confinement.”

White with Prisoners Legal Services says the bill builds on the reforms that state lawmakers passed in 2018 to establish baseline standards for living conditions. “It’s asking the Commonwealth to make a commitment to baseline human dignity, to meeting people’s needs and to lifting up a culture that will focus on the potential for human and community growth and safety,” she told Bolts.

Massachusetts law allows legislators access to its correctional facilities. In early January, a week before the public safety committee hearing, Uyterhoeven and Steven Owens, another representative who supports the bill, made a surprise visit to Souza, the maximum security prison, to examine the isolation conditions themselves.

One week before their visit, a man had set his cell on fire after receiving no response to his repeated requests for medical care. Uyterhoeven said the stench of smoke still lingered inside the halls. Men they encountered in the SAU complained about the lack of medical and mental health care and said they rarely received the mandated 90-day reviews of their placement in solitary. Uyterhoeven says everyone they encountered in isolation was Black or brown except for one man.

The lawmakers decided to measure the outdoor recreation cages after hearing the men call them “dog kennels.” They ranged between about 200 and 300 square feet, with nothing inside and a covering overhead so that you can’t see the sky.

“What I saw on the visit was truly mortifying,” Uyterhoeven recalled. “It’s just such a clear violation of the law.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.