Fake Trump Elector Is Running in Wisconsin This Week, Alongside Other Big Lie Supporters

Conservative efforts to gain local power over election administration are on the ballot tomorrow in one the nation’s premier swing states.

Daniel Nichanian | April 4, 2022

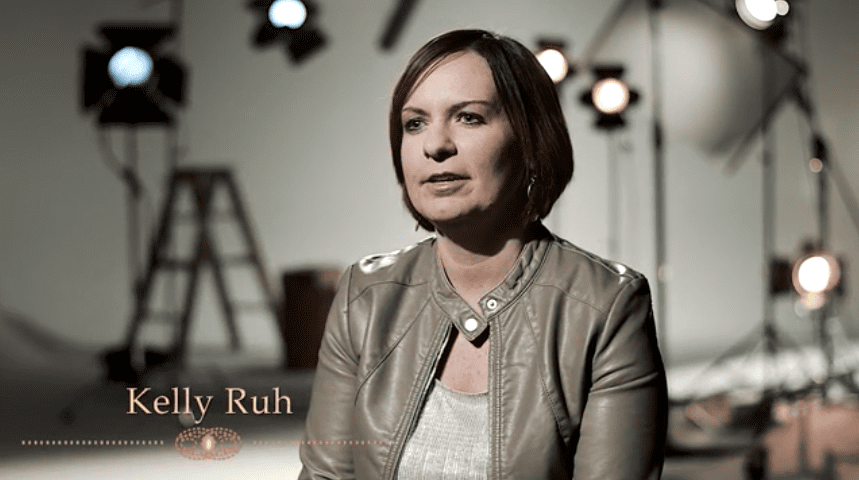

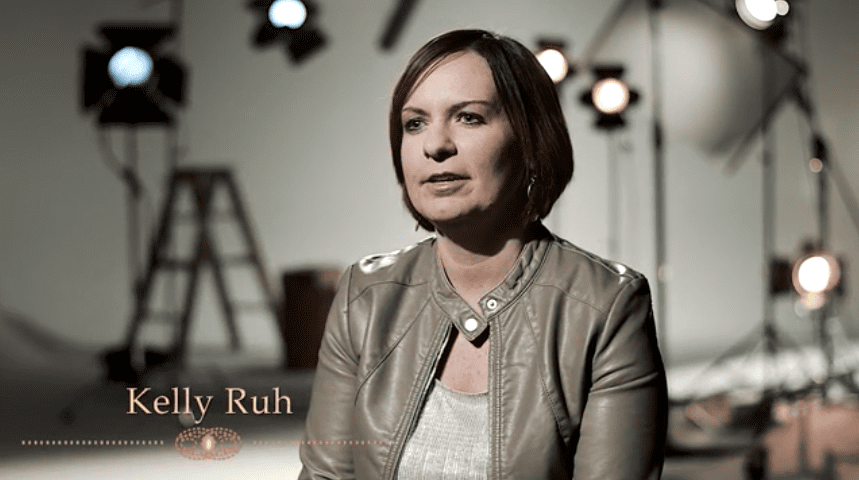

Kelly Ruh, a city council member in northeast Wisconsin, joined other Donald Trump supporters in December 2020 to pose as a presidential elector and mail certificates to the National Archives and Congress falsely declaring that Trump had won the state, even though Joe Biden had just defeated him by more than 20,000 votes. She was one of the 84 fake electors spread around the country who tried to overturn the election that month.

Weeks later, as Trump supporters gathered at the Capitol in D.C. on Jan. 6, Melinda Eck organized a “Stop the Steal” demonstration back home, in Green Bay. “There’s a lot of people that are supporting our president, and we don’t want to back down from this because we may lose our republic if we do,” Eck said at the rally.

Biden has since become president, but the Big Lie has not quelled, especially in Wisconsin. Some conservatives in the state can’t move past Trump’s loss, as they continue to question the presidential results, push for their decertification, and harass election officials with unsubstantiated accusations. Now they are hoping to consolidate more power over the mechanics of election administration.

Eck and Ruh will both be on the ballot tomorrow when Wisconsin hosts its local elections. They are among a string of conservatives seeking municipal and county offices throughout Wisconsin after casting doubt on Biden’s win—with some like Eck and Ruh having actively attempted to thwart it.

These two Stop-the-Steal activists are running for city council seats in the Green Bay region, where some on the right are determined to not only block outside funding to cash-strapped local election systems but also to stop local authorities from actively reaching out to voters. Further south, a Republican lawmaker who oversees the legislative committee that ordered an audit of the 2020 election is running for county executive in Kenosha, one of Wisconsin’s most competitive counties. A judge who wants a seat on Wisconsin’s second most important court is touting the endorsement of Michael Gableman, a former state supreme court justice who released a report last month calling for the 2020 presidential election to be decertified. And a candidate for mayor in Waukesha, in the Milwaukee suburbs, just cheered Gableman’s report.

Elections this local rarely steal the spotlight. But local officials conduct a lion’s share of election administration, managing procedures like how ballots are cast and counted, shaping the ease with which voters can register, and deciding how to allocate election funding and assist voters.

Trump’s efforts to sway the 2024 presidential election hinge on the results of hundreds of similar elections around the country. The former president was in nearby Michigan this weekend stumping for two Republicans running for attorney general and secretary of state, the state’s chief election official, who are parroting his false claims that 2020 was marred by widespread fraud.

In Wisconsin, conservatives have pushed to restrict the powers of local elections offices while fanning conspiracies about the outside assistance that local governments received in 2020 as they struggled to respond to the pandemic. The nonprofit Center for Tech and Civil Life (CTCL) issued grants that year to support local election administrators, grants backed by a large donation from Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan—a fact that Republicans nationwide have since seized on to allege such funding skewed the 2020 election. Gableman has also said it was improper for Wisconsin cities to use those funds to reach out to Black residents.

Many GOP-run states have since passed laws that ban local officials from partnering with non-profit groups, among other major restrictions on their authority. But in Wisconsin, GOP lawmakers must deal with a Democratic governor who can veto their bills. At least for now, Wisconsin’s local officials can still decide whether and how to forge partnerships, and how to reach out to voters, intensifying tensions around who occupies those seats.

The issue has rocked local politics in Green Bay, the state’s third most populous city and one of roughly 2,500 jurisdictions nationwide that accepted CTCL grants in 2020. In October 2020, Ruh and a group of fellow conservatives filed a failed lawsuit against Wisconsin’s election commission, demanding that it block Green Bay and other municipalities from using CTCL grants. Ruh, an alderperson in the neighboring town of De Pere who is up for re-election this week, later posed as a fake elector and has since been subpoenaed by Congress.

Last fall, Green Bay resident Kimber Rollin filed an ethics complaint against Mayor Eric Genrich over the grant. (Genrich is not up this year but his critics are trying to force a recall.) The Green Bay Press-Gazette identified Rollin as one of at least two candidates spouting the Big Lie who are running for Brown County board, alongside Leanne Cramer.

And just last month, Green Bay’s council held a raucous meeting that touched on whether to accept assistance in the future. Besides criticizing the city for accepting the 2020 grant, local conservatives are also attacking the city for mounting campaigns to encourage voter turnout. “We should not have outreach at all,” said alderperson Chris Wery, who is not opposed this year.

How or whether to work with non-profit organizations, in terms of accepting grants or partnering with local groups that may help with voter outreach, will come down in part to the alderpeople who will be elected this week. Eck, the activist who helped organize the local Stop-the-Steal rally on January 6, is hoping to grab one of the districts where the incumbent is retiring.

Michael Poradek, Eck’s opponent, told Bolts that he disagrees with those who say the city should shun voter outreach. “How can we use our neighborhood associations throughout the city to encourage voting?,” he said. “Are there creative ways we can continue to reach out to get everyone to be voting?”

But Poradek also said he would not support accepting future grants from CTCL because he wants to minimize the involvement of organizations outside Green Bay. He also said that he “accepts the outcome” of the 2020 election, during which he worked as a poll worker. Podarek added that he fears calls to ban external assistance risk also cutting ties with local community organizations, like the League of Women Voters, that are key in reaching out to residents.

Eck did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Ruh and her opponent, Pamela Ganz.

Outside interest has poured into the Green Bay area. Restoration PAC—a national conservative group that is funded by Richard Uihlein, a billionaire who has been friendly to Stop-the-Steal groups—released an ad that repeats the claims that the city’s current leadership enabled fraudulent activities. A competing group called Open Democracy PAC has also jumped into these local elections, supporting candidates that Restoration PAC opposes. The PACs are spending tens of thousands of dollars on digital ads.

While Republicans in Wisconsin haven’t changed election laws since Trump’s loss as have other GOP-led states, they have fueled Trump’s lies by commissioning a series of reviews of the 2020 election. Under the guise of improving voter confidence, such reviews can sow perceptions of malfeasance, even absent evidence of wrongdoing.

The Wisconsin Legislative Audit Committee, co-chaired by state Representative Samantha Kerkman, ordered an audit of the presidential election along party lines in early 2021, which ultimately found no evidence of widespread problems. Kerkman is running for Kenosha county executive this week against Democratic Clerk of Courts Rebecca Matoska-Mentink.

Republican leaders also commissioned a report from Gableman, the former conservative justice who has publicly declared that 2020 was marred by fraud. Gableman returned a report last month recommending a wide array of measures like decertifying the 2020 presidential election results and exiting a national bipartisan organization that helps states maintain voter rolls. His report has made waves among local candidates. “I believe the Gableman Report has exposed fraud in the 2020 WI election,” Julie Saib, a candidate in tomorrow’s mayoral election in Waukesha, wrote on Facebook last month. Saib did not respond to a request for comment on what she would do differently as mayor.

Also in Waukesha County, Maria Lazar is touting Gableman’s endorsement, as well as support from a fake Trump elector, on her campaign website in her run for a seat on Wisconsin’s Court of Appeals, the Appleton Post-Crescent reports. The incumbent Lazar is looking to unseat, Lori Kornblum, has seized on those connections, telling the Post-Crescent, “My opponent is supported by extreme interests trying to unconstitutionally overturn the 2020 election.”

Tomorrow’s elections are just the first round in a larger high-stakes battle around voting policies in Wisconsin this year. Voters will return to the polls in August and November to elect their lawmakers, governor, and secretary of state, among other public officials.

Republicans could pass more sweeping changes to Wisconsin election rules if they manage to unseat Democratic Governor Tony Evers in November. Rebecca Kleefisch, a former Republican lieutenant governor who is now the GOP frontrunner to challenge Evers, would not say whether she would sign a bill allowing the state’s legislature to overturn a presidential election. She has called it “awfully premature” to weigh in, even though Republican lawmakers in the state have joined Trump’s lawsuits attempting to give legislatures final say on certifying elections.