A New Crackdown on Ballot Initiatives Unnerves Florida Organizers

The new Republican law threatens volunteers with more investigations and criminal punishment, even as Ron DeSantis faces allegations of illegally meddling in ballot measures.

| May 7, 2025

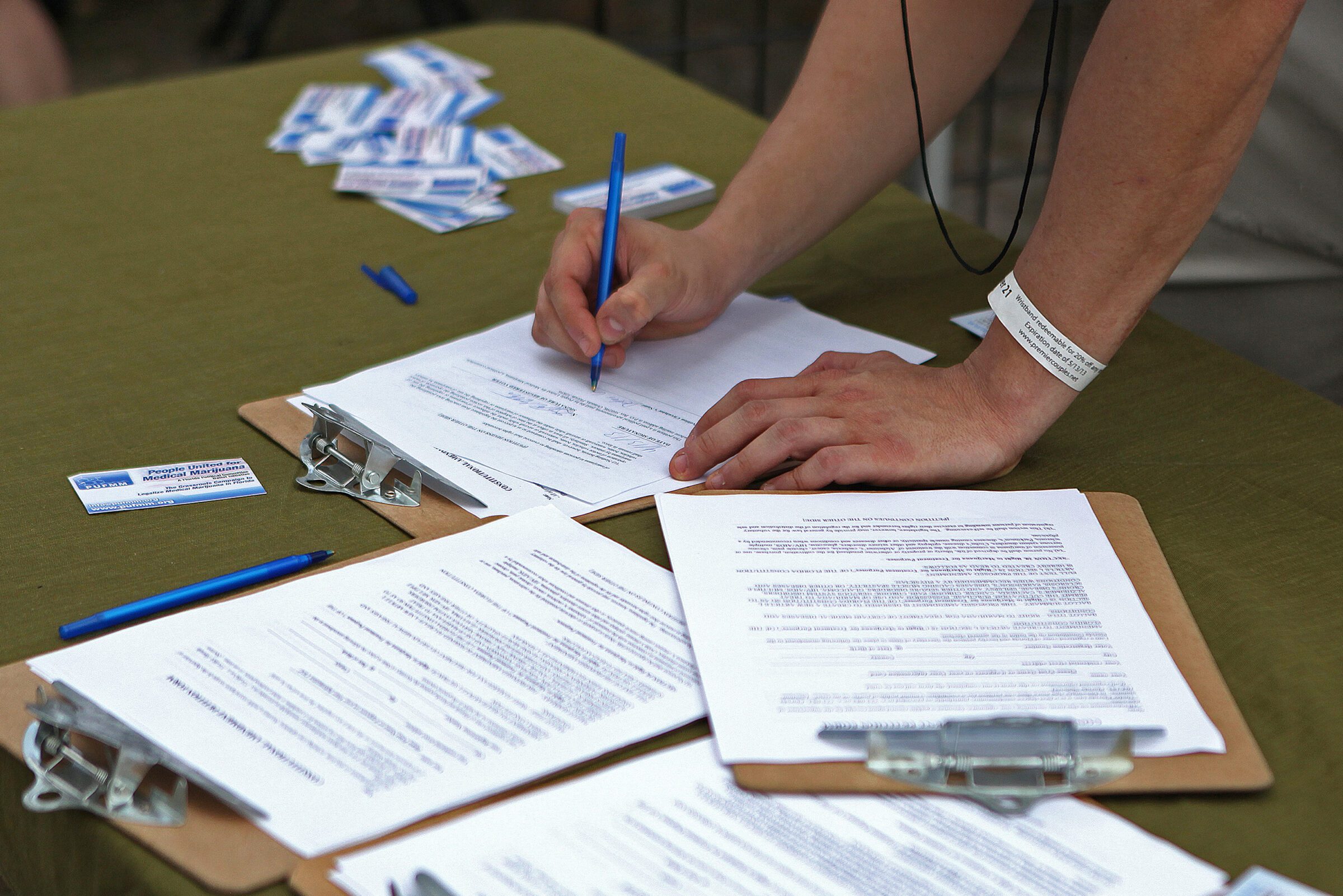

Volunteers with the League of Women Voters of Florida are often seen at farmers markets, book clubs, parades, and other gathering places, collecting petitions and raising awareness on new campaigns. The League in recent years has become a flag bearer for the citizens initiative process that allows ordinary Floridians to bypass lawmakers and amend the state constitution.

League volunteers were instrumental in the success of the ballot measures that raised the minimum wage in 2020 and restored the right to vote for those convicted of a felony in 2018. Last year, they helped the effort to collect the roughly one million signatures that placed measures to legalize abortion rights and marijuana on Florida’s ballot.

But a new law, signed by Governor Ron DeSantis on Friday, will turn common tactics the League uses to gather signatures into a criminal offense.

The legislation makes it a felony for a volunteer to collect more than 25 signatures for a campaign from people outside their family without getting approval from the state, which requires background checks and training. At a single community event, individual volunteers collect far more signatures than that cap, according to the League’s co-president Cecile Scoon, and groups will have to overhaul training and outreach tactics. The League will teach volunteers to comply with the law, but the looming threats “will chill people from wanting to participate as signature gatherers or even as signatories,” Scoon warned.

“It is turning those places where citizens were free to discuss and share information into potential liabilities for the organization that supports them,” she told Bolts. “People are not going to want to get involved. They don’t want to be at risk of any criminal penalties.”

House Bill 1205, branded by its Republican champions as a measure to prevent fraud, also introduces new restrictions on who can even volunteer, requires organizers to undergo more training, shortens the deadlines to turn in signatures, and sets up a minefield of new criminal violations. It also imposes a heavy financial cost on organizers upfront.

Opponents of the law already filed a lawsuit against it in state court on Monday. A coalition led by Florida Decides Healthcare, a political committee that is currently gathering signatures for an initiative to expand Medicaid access, claims the restrictions violate free speech rights and undermine a process guaranteed by Florida’s constitution.

“Who are they targeting? A mom helping her book club collect petitions, a veteran lending a hand at their local food drive, a senior who wants to gather signatures at church,” Holly Bullard, the campaign’s co-chair, said at a press conference announcing the lawsuit on Monday. “These aren’t bad actors, they’re the heart of our communities. But politicians in Tallahassee want to treat them as criminals.”

Voting rights advocates are concerned that Florida will now wield the slew of violations created by the law to target routine political activity and investigate grassroots organizations and volunteers over minor clerical errors. Ahead of the 2024 elections, DeSantis launched investigations into the validity of over 35,000 signatures, submitted on behalf of the abortion rights measure, that had already been verified by local officials. Florida’s elections police, a force created in 2022 on DeSantis’ urging, then went to the homes of some people who had signed petitions to question them, a tactic derided by critics as voter intimidation. The abortion measure ultimately fell short of the 60 percent it needed to pass in November.

The new law further expands the reach of this elections police force, known as the Office of Election Crimes. “They would bring themselves into every initiative, and there is not a lot of transparency over how they operate,” said Brad Ashwell, state director for All Voting is Local.

“We’ve seen the arrests, we’ve seen people being approached and doors being knocked on,” he added. “It’s very ominous.”

Republicans have recently imposed new restrictions and criminal statutes on the initiative process in other states, including a barrage of new regulations this spring in Arkansas. Organizers there say they’re unsure of whether they’ll be able to pursue more initiatives and are fearful that they may end up “on the hook for a crime.”

DeSantis has been calling for new restrictions on Florida initiatives ever since he accused the abortion rights measure of fraud last fall. But ironically, the debate over HB 1205 was taken over in the final weeks of the legislative session by allegations that DeSantis himself illegally meddled in the abortion and marijuana measures that were on the 2024 ballot.

The governor directed Florida’s Department of Transportation last year to run ads warning that recreational marijuana would cause a spike in DUIs and crashes. Florida’s health department also funded ads promoting the state’s six-week abortion ban, which had been signed into law by DeSantis and would have been overturned by one of the initiatives on the ballot.

This spring, lawmakers across parties accused DeSantis of misusing public funds for campaign expenses. They pointed to a chain of payments that went through the Hope Florida Foundation, a nonprofit organization led by First Lady Casey DeSantis.

“This is looking more and more like a conspiracy to use Medicaid money to pay for campaign activity,” Republican state Representative Alex Andrade, who led a legislative inquiry into the funds, said at a press conference.

The investigation uncovered that the Hope Florida Foundation had paid $5 million each to two organizations that then made donations of the same size to the campaign to defeat the marijuana measure. The foundation had just received a $10 million donation from Florida’s largest Medicaid provider, which faced accusations of overcharging prescription drugs, as part of a settlement brokered by the state. Andrade has called for a federal probe to determine whether the governor and attorney general committed fraud and money laundering.

As the scandal unfolded, Republicans inserted in HB 1205 a ban on using public money to advocate for or against a citizens initiative. The provision is seen as a rebuke to DeSantis, and was the only part of the legislation that Democrats have said they support.

All in all, though, Republicans have cast the law as a response to actions of the organizations who qualified the 2024 measures, rather than those of DeSantis. Senator Don Gaetz, who sponsored the bill, acknowledged the state “engaged in behavior that will now be unlawful.” But he also pointed to a report released by Florida’s office of elections crime last year that alleged that “out-of-state contractors and too many of their paid petition circulators routinely are committing fraud, deception, and criminality.” That’s the same report that DeSantis used last fall to justify investigating the abortion rights measure and to call for restrictions this year.

An investigation by NBC uncovered serious methodological issues with the report, including miscalculations on the number of suspicious petitions and factual misstatements.

Gaetz and DeSantis did not reply to requests for comment.

But even if the accusations don’t bear out, the initial stamp on DeSantis’s claims of fraud still tarnish the reputations of the campaigns and “make voters think something nefarious is going on,” regrets Adam Ginsburg, the former voter protection director for Florida Democratic Party Coordinated Campaign. “There is an effort to preemptively delegitimize the results of elections or initiatives before they occur to create a pretext to try to challenge the results afterwards.”

The new legislation would cause state inquiries to multiply. One provision triggers an investigation by the state’s elections police into any campaign if more than 25 percent of petitions are found to be invalid during the state’s routine review process.

Initiative organizers always collect far more petitions than needed, expecting many to be found invalid due to clerical issues or legal challenges. Rejections are typically due to inconsistent or changed signatures, misspellings or other minor issues. Florida does not have a cure process for fixing invalid petitions, and the state does not notify signatories when there is an issue. Ashwell says that makes it unlikely that any citizens’ initiative would meet the 25 percent validity rate, inviting state officials to interfere with any proposed amendment that they disagrees with.

“Even the best run campaign isn’t going to meet the standards they are setting,” Ashwell said.

If anything, by cutting the timeframe for organizers to review and turn in each petition, HB 1205 may make errors more common.

Organizers previously had 30 days to submit each petition to the state after it was signed. A measure’s sponsors used that window to vet each petition and contact signatories to correct any issues. Groups already sometimes struggle with that window; the elections police last year fined the sponsors of the marijuana initiative for late filings, resulting in a $120,000 penalty. But the new rules allow only 10 days to return each petition, and increase the maximum fines from $50 up to $2,500 for each petition that misses the deadline. This risks denying organizations the time they need to ensure they meet the validity rate threshold and potentially bankrupting them.

“That’s the time they need to do internal validation. That is the time they use to make sure there is no fraud going on,” Ashwell said. “This is at odds with what they say they want to do. They are essentially removing their ability to catch problems before they submit them, which will increase the invalidation rates and lead to more investigations.”

The election reform package creates an array of other hurdles, costs, and violations that citizens campaigns will have to navigate. Supporters will have to include their drivers license number or a portion of their social security number for their signatures to be valid. Organizers will have to pay a $1 million bond to the state as part of the petition process. Local elections officials will be required to send a mailer to all petition supporters notifying them of their right to withdraw their signature—and those costs may be passed on to the campaign sponsors.

The new law also bans people with felony convictions from collecting signatures unless they have had their voting rights restored.

Voters easily passed a constitutional amendment to restore voting rights for people who complete a felony conviction in 2018, the same year DeSantis was elected. DeSantis then signed a law weakening that measure by requiring that people pay off court fines and fees before regaining their rights. That created widespread confusion among formerly incarcerated Floridians since the state does not systematically track outstanding legal fees or eligibility.

In 2022, DeSantis’ newly minted police force arrested 20 people with past felonies for election fraud, even though officials had previously told some of them that they were allowed to vote, creating a climate of fear for people voting with a past felony conviction. Scoon says HB 1205 will expand that climate to future ballot initiatives. Volunteers subjected to felony charges under the new law could be disenfranchised themselves.

“Here you are, trying to keep democracy going, and you can lose your right to vote,” she said. “Even if someone thinks you make a mistake, you’ll end up fighting for your own right to vote.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.