The Escalating Race to Redistrict: Your Questions Answered

How are the new maps changing the midterms? Would proportional representation help? Why are courts not doing more? You asked, and we’ve got answers about mid-decade redistricting.

| December 19, 2025

Spurred by President Trump, Texas Republicans triggered a redistricting escalation this summer, and the effects on the midterms look increasingly unpredictable. Five more states have adopted new congressional maps since September, and many lawsuits are now moving through courts.

Come 2026, more states are likely to join the fray. And the Supreme Court will rule on a major case that may gut the Voting Rights Act and its legal protections against racial gerrymandering.

We asked our readers to send us their questions about this landscape, as part of our series “Ask Bolts.” Today we are tackling six of them, with help from a few voting and redistricting experts.

Navigate to the question that most interests you, or simply scroll down to explore them all:

How is mid-decade redistricting constitutional?

How many seats will each party gain via these new maps?

How can it be “too late” for courts to weigh in on maps that just passed?

What are Democratic-run states up to?

Can state constitutions shield against gerrymandering?

What about proportional representation?

Read on to learn about the redistricting landscape, and revisit older installments of our “Ask Bolts” series.

Want updates on redistricting?

Sign up for our newsletter.

I don’t understand how any mid-decade reapportionment is remotely constitutional. Isn’t it supposed to be done once based on the new decennial census? — @betsy-cazden, on BlueSky

In 2006, the Supreme Court ruled that neither the federal constitution nor federal law ban mid-decade redistricting. In a case that upheld Texas Republicans’ then-new map targeting congressional Democrats (plus ça change…), Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, “The Constitution and Congress state no explicit prohibition,” That pronouncement has largely closed the door for plaintiffs to sue on these grounds in federal court.

Still, Justin Levitt, a law professor at Loyola with whom we shared this question, agrees with its spirit. “Your reader’s instinct that this should only be done once a decade is absolutely right,” said Levitt, who has experience litigating redistricting cases. “The whole point of redrawing is to make sure that, once we know where the people are, we can recalibrate where the districts are growing, and so it only makes sense to do this once a decade.”

Repeatedly redrawing maps, he says, “sure seems like this is one way for incumbents to stop citizens from evaluating their own representatives.”

But Congress has the authority to create a prohibition where Kennedy found none.

In fact, several bills have been filed this year, one by Republican U.S. Representative Kevin Kiley, whose California district was redrawn by Democrats this fall, and another by Democratic lawmakers, to ban states from redrawing maps mid-decade unless they’re ordered to by a court.

I’d love a count of D/R pluses and minuses through this redistricting. Where are we at this moment? What’s the worst case for either side? — @mattkopans, on BlueSky | So many states are adopting new maps I don’t have a big picture anymore. What’s the count of how many seats Republicans will gain through new gerrymanders? — Suzie, from California

Trump hoped for big gains when he pressured GOP-led states to redraw their maps. After Texas kicked it off, Missouri and North Carolina followed with new maps. Ohio Republicans were legally required to pass a new map anyway; they used that to target longtime Democratic incumbents. These moves alone were shaping up to give Republicans as many as 9 new seats.

But other developments have brought this battle closer to a draw. That includes Democrats fighting back in California, where voters massively approved Prop 50, and a Utah judge striking down the GOP’s 2021 gerrymander. It also includes setbacks in Trump’s plans, most notably Indiana Republican senators rejecting a gerrymander last week.

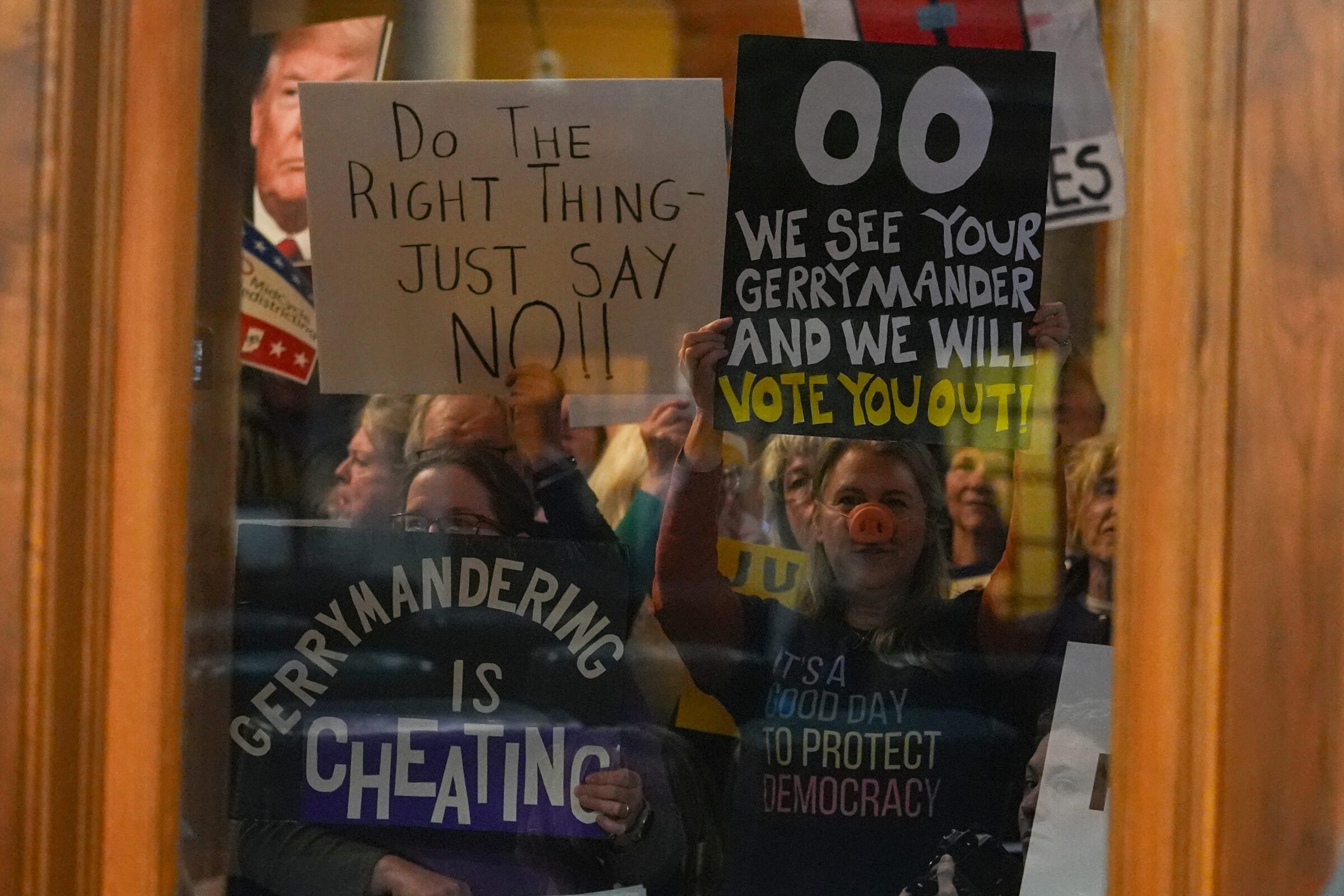

Plus, Missouri Republicans may see their new map blocked. Organizers collected over 300,000 signatures to force a veto referendum; for now, GOP officials say they plan to use their new map anyway.

So where does this leave the overall count?

All in all, six states that adopted new maps so far this year: California, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, and Utah. Several are facing legal challenges, but Missouri’s is in the most immediate limbo.

The simplest method involves calculating how many flippable seats have become more red or more blue due to redistricting, based on how the new districts would have voted in the 2024 presidential election.

The Texas GOP redrew five Democratic-held seats to make them more Republican-friendly and increase its odds of flipping them. They did the same with one seat in each of Missouri and North Carolina. In Ohio, the GOP redrew two seats in that way but also made a seat it was expected to contest more Democratic-friendly. In Utah, a court remade a Republican district into a Democratic seat anchored in Salt Lake City. And California Democrats redrew five GOP-held districts to make them more Democratic-friendly.

By this measure, the GOP has gained a slight overall advantage so far via redistricting: one to two seats across the six states with new maps, depending on the fate of Missouri’s.

Two more states have yet to redraw their maps but have begun that process: Florida, where Republicans are talking of targeting as many as five seats, and Virginia, where Democrats are talking of targeting as many as four seats.

Depending on whether either or both states complete a redraw next spring, the range of possible outcomes is very wide, from an overall Democratic shift of up to 3 seats (if Democrats redraw the Virginia map as aggressively as they could while Republicans do not redistrict Florida) to a overall Republican shift of up to 7 seats (if those roles are reversed).

And that doesn’t account for Louisiana or other states that may jump in if the U.S. Supreme Court guts the VRA in time for them to draw new midterm maps—a major unknown given the court’s unpredictable calendar. It also doesn’t include Kentucky, Maryland, or South Carolina, where leaders have refused political pressure from national politicians so far but could still change their mind, or New York and Wisconsin, where courts are considering lawsuits against existing congressional maps.

| How many targeted seats got bluer (as measured based on the 2024 presidential race)? | How many targeted seats got redder (measured based on the 2024 presidential race)? | |

|---|---|---|

| Total across the six states that adopted new maps | 7 | 8 to 9 (depending on Missouri) |

| Total across the eight states that have begun or completed a process | 7 to 11 (depending on Virginia) | 8 to 14 (depending on Florida and Missouri) |

But this method is imperfect because not all shifts are made equal. In the Austin and Houston regions, for instance, the GOP took staunchly Democratic seats and made them so conservative that Republicans are virtually certain to win them. But in North Carolina, Democratic incumbent Don Davis was already very vulnerable, and the GOP made his district a few percentage points redder. The targeted Ohio Democrats could also survive, especially Greg Landsman, whose new Cincinnati-based district would have voted for Trump by two percentage points last year.

Plus, California Democrats used their new map to shore up many of their own incumbents, beyond just targeting GOP seats—which could help them save millions of dollars trying to defend these seats.

To assess the national count through this more nuanced lens, we can use the ratings published by the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, an elections forecaster that rates every U.S. House race on a seven-point scale (from safely Democratic to safely Republican), as a proxy to distinguish between these various sorts of redrawings.

Since August, they’ve changed the ratings of 23 seats due to redistricting. Some seats have swung by the maximum of six rating steps (e.g. safely Republican to safely Democratic, or vice-versa), others by as little as one rating step (e.g. toss-up to lean Republican).

And if the petition drive does block Missouri’s new map, Democrats would be the ones to gain an advantage overall across these ratings—with a net shift of six ratings steps in their favor in these districts and states.

Of course, the effects of redistricting go well beyond partisan swings. Nathaniel Rakhish, an elections analyst and managing editor of Votebeat, flags a whole array of other consequences, “such as less competitive districts, a huge amount of churn in the California and Texas congressional delegations, and chaos for election administrators.”

And if the Supreme Court does gut the VRA, that’d affect a lot more than who controls Congress. It would decimate representation for voters of color throughout the country—not just at the congressional level, but also in local bodies like county commissions and school boards. Bolts has reported on what such a world would mean for Black voters in West Tennessee.

How can they say it’s ’too close to the election’ to make changes in Texas when the new maps themselves were just drawn!? Isn’t that ‘too close to the election’ too? — @joeprodemocracy, on BlueSky

Many scholars and legal writers share your frustration at the Supreme Court’s frequent pronouncements that it’s too late for a court to address complaints about an election. This idea is known as the Purcell principle, named after a 2006 ruling in which the justices said it was too close to an election to grant an injunction against Arizona’s voter ID requirements, lest voters be confused by a late change.

Critics have long faulted the court for applying this idea inconsistently and with no guidelines; they’ve also said leaving a suppressive rule in place may be more harmful than voter confusion.

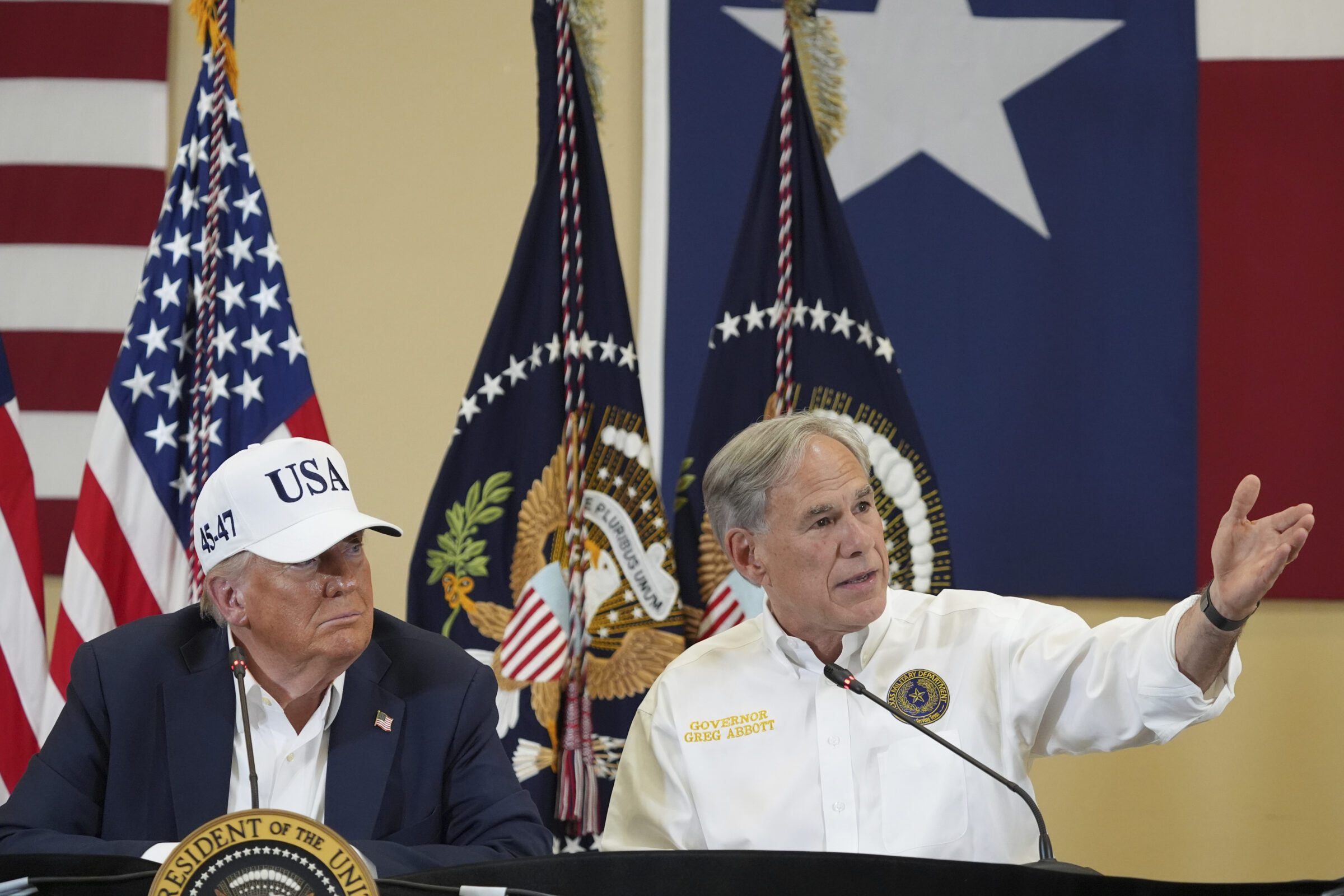

These worries came to a head this fall in the lawsuit against the Texas map. Governor Greg Abbott signed the map into law on Aug. 29, just three months from the Dec. 8 filing deadline for candidates. Then, when Judge Jeffrey Brown struck down the map in November, Texas officials argued it was already too late for judges to intervene and they won at the Supreme Court.

Richard Pildes, a law professor at New York University who works on election law, wrote in Bloomberg that the decision “creates an apparent path for state legislatures to game federal law: Change your election policies close to the election—which can mean perhaps even a year before the election—and Purcell might prohibit the federal courts from interfering.” The fear is that states may keep weaponizing Purcell and adopt a law at such a time that no judicial review will be acceptable to the Supreme Court. By the time the law passes, judges are already too late.

Where are state Democrats who have control not redistricting because the legal barriers to doing so are insurmountable, and where are they not redistricting because they don’t wanna? — @proptermalone on BlueSky

Four GOP-run states have drawn new maps this year, while California is the only one run by Democrats. So what about the seven other Democratic-run states where the GOP holds some congressional seats? We shared this question with David Nir, editor of The Downballot, who recently wrote guides to every state’s redistricting process.

“Democratic lawmakers in Illinois, Maryland, and Oregon could draw new maps today that could be in place in time for the 2026 elections,” Nir said. “They might face legal challenges, but they have the power to act now.”

But despite prodding from Hakeem Jeffries, the New York Democrat and House Minority Leader, at least some Democratic leaders in those states have resisted the idea of redrawing maps.

In the four other states—Colorado, New Jersey, New York, and Washington—it’d take a state constitutional amendment for lawmakers to circumvent the independent commissions that are currently in place and redraw congressional maps. In New Jersey and New York, Democratic lawmakers have the votes to begin the process right away, though they couldn’t finish it before 2028. (There is, separately, a lawsuit that’s trying to force changes to New York’s map by 2026.)

In Colorado, Democrats lack the supermajority they need to advance an amendment through the legislature but, Nir says, “they can do it via ballot initiative, and there’s a grassroots effort currently underway to do just that.” And in Washington state, he continued, “Democrats lack the necessary two-thirds supermajorities to place one on the ballot, and the state doesn’t allow initiatives that amend the constitution.”

What states have constitutional rules against gerrymandering, and how does this affect the electoral map? — @fluxandflow on BlueSky

In Utah, where voters approved guidelines against gerrymandering in 2018, courts invoked that initiative earlier this year to strike down the GOP-drawn map and force a fairer map. Does that signal the path out of the current battles? We asked Quinn Yeargain, a state constitutional scholar at Michigan State University College of Law.

“Establishing state rules against gerrymandering and pursuing lawsuits in state courts offer strong options for challenging unfair maps,” Yeargain said. “But neither answer is perfect.”

A number of states have adopted constitutional amendments that specify criteria that new maps must meet, but Yeargain cautions that it’s then up to judges to actually apply them, telling Bolts, “These rules ultimately hold whatever power the court enforcing them thinks they ought to have. “In Florida, even as the state Supreme Court hasn’t technically killed the state constitution’s ban on partisan gerrymandering, it seems clear that it won’t stand in the way of even a brutal gerrymander.”

Even in states with no explicit constitutional language against gerrymandering, Yeargain continued, “state judiciaries hold promise; fair maps exist in Pennsylvania because its supreme court held that the state constitution’s Free and Equal Elections Clause prohibited partisan gerrymandering. But caution is warranted here, too: Too many state courts have held, just like the U.S. Supreme Court did in 2019, that they’re incapable of resolving claims of partisan gerrymandering.”

Moreover, Yeargain added, “even a willingness by a court to step in once doesn’t guarantee that it’ll consistently do so. In 2022, as control of supreme courts in North Carolina and Ohio flipped, so, too, did the opportunities to strike down unfair maps.”

In short, state reforms are no panacea. “Reformers can certainly pursue both constitutional amendments and litigation in whichever states they can,” Yeargain says, naming Missouri, Nebraska, and Ohio as some of the states that allow for ballot initiatives (such an effort failed in Ohio last year). “But given that neither option is feasible in states that are some of the worst offenders—like Texas—it is worth being realistic about the impact. At the end of the day, state-by-state solutions aren’t a long-term solution, and Congress would have to step in to ensure elections are fair nationwide.”

What nationwide reforms could address the increasing amount of uncompetitive districts with essentially predetermined winners? Could Congress enact independent commissions in every state? Multi member districts? Proportional representation? — Tommy P., from Pennsylvania

We shared this question with Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at the think-tank New America who vocally champions implementing proportional representation in the U.S..

Drutman sees multiple pitfalls with the current system of single-winner districts, where “each district gets one winner and the person with the most votes wins.” For one, “because there can only be one winner, voters and politicians are forced into just two big-tent coalitions, which then sort geographically. And as politics has become nationalized, split-ticket voting has collapsed and geographic sorting has become nearly total. Hence safe seats everywhere.”

Plus, when you cut up a state into single-member districts, “somebody must draw many lines to guarantee equal size,” and Drutman flags this is where politicians are able to manipulate results. “Line-drawers have thousands of possible maps to maximize advantage—hence partisan gerrymandering.”

For Drutman, independent commissions cannot resolve the issue. They “can mitigate manipulation at the margins” but “cannot manufacture competitive terrain that doesn’t exist,” so “even states with independent commissions still have mostly safe seats.”

In a system of proportional representation, instead, a district elects many members, and parties get a number of seats proportional to their share of the vote. This may help third parties grow, since they could win seats with even a small share of the vote; it would also diminish the importance of redistricting since no party could win all seats, even in a favorable district.

“Now multiple parties can compete and win across regions,” Drutman says, “no more winner-take-all lockouts, every vote matters. And with fewer, larger districts, there are fewer lines to draw.”

A 1967 federal law, known as the Uniform Congressional District Act, currently requires that states use single-member districts. But Congress could amend that law to mandate that states use proportional representation instead; no constitutional amendment would be needed.

States could adopt this method for their legislatures without any federal approval; proponents like Drutnam are already pushing proposals to do just that in several states, including California. An Oregon lawmaker, Democrat Farrah Chaichi even introduced legislation in 2023 to switch state House elections to this system; her proposal was that all Oregonians vote in one statewide election that would decide the chamber’s composition proportionally.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.