Mississippi Keeps the Door Firmly Shut on Ballot Initiatives

Three years after the state supreme court voided direct democracy in Mississippi, all legislative proposals to revive it died again this week.

| April 4, 2024

Charles Taylor was working to put Medicaid expansion on the ballot in the spring of 2021, when Mississippi’s supreme court stepped in and voided any avenue for direct democracy.

With the state’s Republican officials refusing to expand the program as provided by the Affordable Care Act, leaving hundreds of thousands in the lurch, Taylor had hoped that a ballot initiative powered by the signatures of tens of thousands of citizens would break the logjam, as it had in other states. “We wanted to take it out of the hands of the legislators and put it into the hands of the people,” recalls Taylor, who leads the state chapter of the NAACP. “I felt confident that it was going to pass.”

His hopes were dashed by the court. At issue: The state constitution requires that a citizen-led initiative collect signatures in all five of the state’s congressional districts; the language was adopted in 1992, before Mississippi lost a congressional seat in the 2000 reapportionment, and it now only has four. The court said in May 2021 that, since there were no longer five districts in which to collect signatures, no initiative could be valid.

The ruling was as literal as it gets; “it stretches the bounds of reason,” complained a dissenting justice. Nevertheless, it brought the petitioning to expand Medicaid and other efforts like it to a screeching halt. And state officials have not fixed the issue in the intervening years. Many GOP leaders have said they want to revive initiatives; but the schemes they’ve proposed have been restrictive—requiring that initiatives receive a supermajority and prohibiting them from ever affecting abortion, for instance—and even those haven’t passed.

This year, again, lawmakers spent months debating bills that would have brought back initiatives in this watered-down form. But the effort faltered for good this week.

A legislative deadline passed on Tuesday that confirmed that all these bills are dead for the year. David Parker, a Republican senator who chairs a key committee, had indicated two weeks ago that the chamber was done considering the issue in 2024.

As a result, Mississippi will spend at least one additional year with no initiatives, despite the state constitution’s promise that residents shall have a right to direct democracy.

“We desperately need a citizen-driven process to put something on the ballot,” Taylor said. “Citizens being able to have the ability to exercise their rights, being able to impact law when possible, is crucial.”

Lawmakers still haven’t expanded Medicaid. Legislation to do so is closer than ever in the current session, with each chamber passing its own bill, but obstacles remain. Taylor regrets that it’s been impossible all these years to just ask voters if they want this. “The coverage gap is just truly a life and death issue,” he said. “More lives can continue to be lost unnecessarily.”

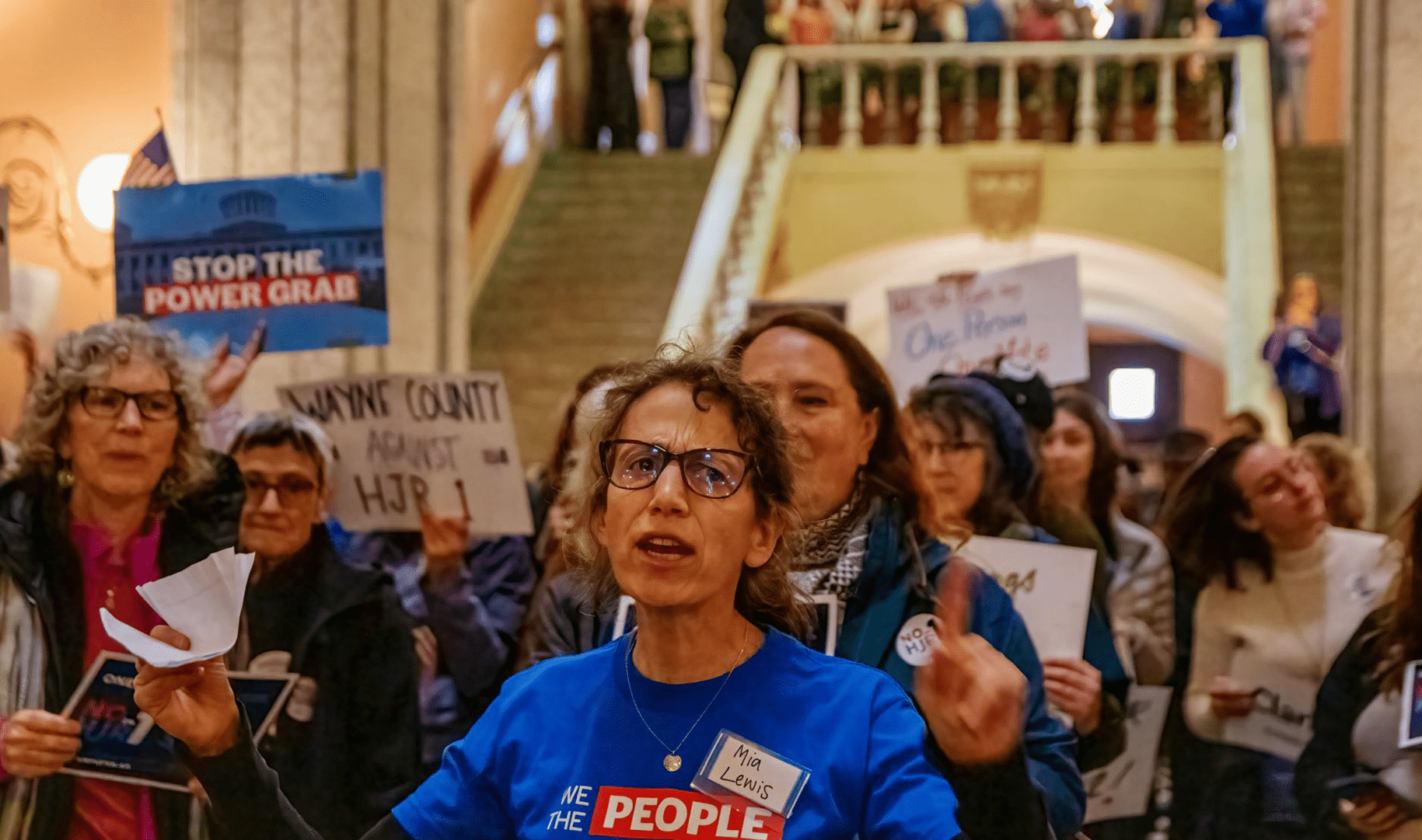

The halting of initiatives in Mississippi for the past three years adds to the recent erosion of direct democracy, typically at the hands of GOP politicians. Republicans have recently made it far harder to qualify measures for the ballot in at least Arkansas, South Dakota, and Utah. Similar proposals are on the table right now in Arizona, Idaho, and Missouri.

In addition, Bolts reported that Republican attorneys general in several states like Arkansas and Montana are routinely using procedural tricks to delay petition drives; Democratic city leaders in Atlanta used similar tactics over the last year to stall a local referendum on the so-called Cop City police training center. Republicans have also tried to raise the threshold needed to pass an initiative once it reaches voters, unsuccessfully in Ohio and South Dakota over the last two years.

In most of these instances, the GOP was retaliating against ballot measures the party opposes on high-profile issues like abortion, Medicaid, and redistricting. In Mississippi, the 2021 lawsuit that ended up striking down initiatives was aimed at Initiative 65, a measure voters overwhelmingly adopted in 2020 to legalize medical marijuana.

This year, Mississippi’s two legislative chambers each passed a bill to bring back initiatives. The House approved Concurrent Resolution 11 in January; it died in a Senate committee on Tuesday, which was the deadline for a bill originating in one chamber to get out of a committee in the other. The Senate, meanwhile, approved Senate Bill 2770 in March; a procedural motion killed it within days.

Democracy advocates who talked to Bolts are frustrated that there won’t be a solution in 2024, but they’re not upset at the failure of these specific bills: Rather than restore the process in place as of 2021, the measures would have revived initiatives only to make them exceedingly difficult to qualify and pass, using the same limitations that Republicans have introduced in Arkansas, Ohio, and elsewhere.

They would have banned ballot measures from addressing abortion, suppressing the issue that has sparked massive progressive organizing. They would also have prohibited citizens from amending the state constitution, which would have left a large swath of other issues out of bounds. For instance, Mississippi’s harsh rules on felony disenfranchisement are codified in its state constitution; changing them, a priority for voting rights groups, requires a constitutional amendment.

The bills would have also required organizers to collect more signatures than used to be the case, ramping up the money and resources needed to qualify a proposal. Finally, they would have dramatically increased the threshold a measure must clear at the polls to be adopted. The House set it at 60 percent, up from 50. The Senate would have gone even further and set it at an unusually high 67 percent.

“It was a scam,” said Paloma Wu, an attorney with the Mississippi Center for Justice who works on democracy cases. “They tried to give the people a cheap ass version of what their powers were.”

Jarvis Dortch, executive director of the ACLU of Mississippi, called the bills to revive the ballot measure process “absurd” and “a joke.” He told Bolts that they would have made it “very much impossible for somebody to be able to get a ballot initiative through.”

Two Republican lawmakers who shaped this year’s legislative debates—Parker, who chairs the Senate’s Accountability, Efficiency and Transparency Committee, and state Representative Fred Shanks—did not respond to Bolts’ requests for comment.

Parker made the decision to not move the bills in the Senate, saying they lacked the votes to pass. He also supported changes like implementing the 67-percent threshold. He said that he wanted to balance his support for initiatives with preventing out-of-state funders from bankrolling policy changes in Mississippi.

Shanks expressed disappointment at Parker’s decision to drop the issue. “The House stands on pushing the ballot initiative back to the people,” he said last month. In shepherding his measure through the House, he supported adding restrictions like a ban on bringing up abortion.

Many Democratic lawmakers objected to the new limits. They pushed for a clean solution instead: legislation to bring back the process as it existed in 2021, simply changing the state constitution’s assumption that the state has five congressional districts to reflect the number it currently has.

Hannah Williams, policy director of Mississippi Votes, a state advocacy group that has played a leading role in trying to fix this issue, says her organization will continue pressuring lawmakers heading into 2025 to bring back ballot initiatives.

“We need more individuals to help us lobby their legislators, to make sure that the things that we want to be able to put on the ballot are protected,” Williams said. Her organization’s goal, she says, is to educate the public as to who is responsible for this predicament and why the proposed solutions were so inadequate.

She hopes to show lawmakers that this is not a partisan issue, since initiatives can be a tool for groups with any political goals.

“I feel like sometimes it gets wrapped up in a ‘this is a left versus right’ thing,” she said. “But the conservative people that we work with, they have issues that they want to be able to put on the ballot too, and us not having a process is hindering really everybody’s right to democracy across the board.”

The state’s GOP leaders have paid lip service to the goal of restoring direct democracy, including during the 2023 elections that saw Republicans retain full control of the state government. But for Dortch, the legislature’s behavior this year is yet more confirmation that politicians just aren’t sincere about wanting to revive an initiative process.

“No one wants to come out and say they don’t want one,” he said.

Mississippi lawmakers are not up for reelection until 2027. This year, the three justices who dissented in the 6-3 decision striking down initiatives in 2021 must run for reelection this fall, though only one of them—James Kitchens—drew any opposition. Justice Dawn Beam, who joined the majority, is also seeking reelection.

Mississippi holds its elections in the shadow of other restrictions on democracy. Just this week, the state House killed a bill that would have set up in-person early voting; the state is one of only four with no early voting. Mississippi also strictly limits how to vote by mail. “If you’re not there from between 7am and 7pm on Election Day, it’s going to be pretty difficult for you to vote in our state,” Dortch said.

In addition, Mississippi has one of the nation’s highest rates of individuals banned from voting due to a felony conviction; the state’s rules on lifetime disenfranchisement were designed in 1890 during an explicitly white supremacist constitutional convention.

Taylor, the NAACP director, says that the refusal to revive ballot initiatives is part and parcel of the broader schemes that are suppressing people’s voices. “This is 100 percent intentional.”

“The state of Mississippi, as long as there’s been a state, there has always been a segment of people that have been disenfranchised,” he added. “You have people who want to carry this into future generations.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom: We rely on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.