DA Candidate Vows to End Death Sentences In Las Vegas, a Capital Punishment Stronghold

Nevada’s Clark County has sent more people to death row than almost any other in the nation under the current DA, who is up for re-election this year.

Sam Mellins | February 14, 2022

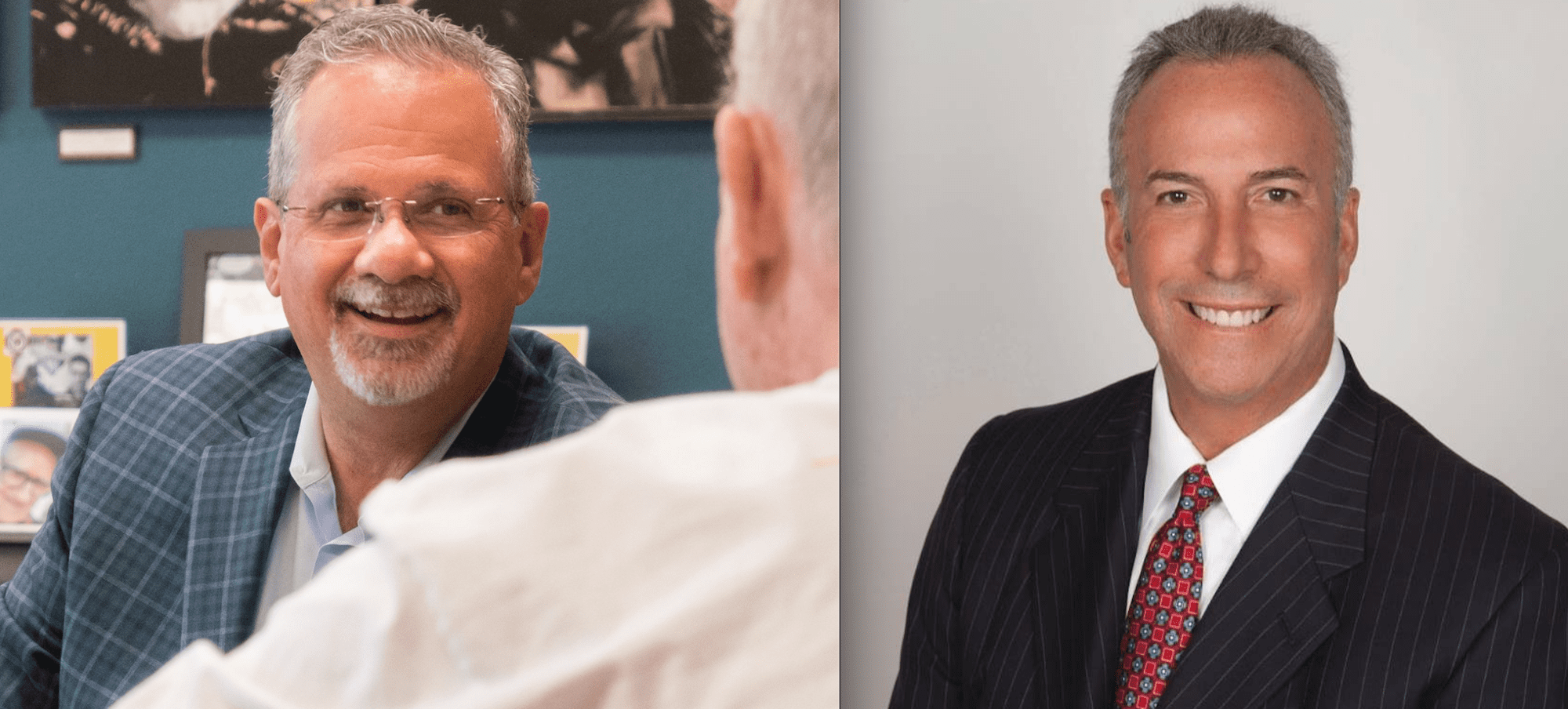

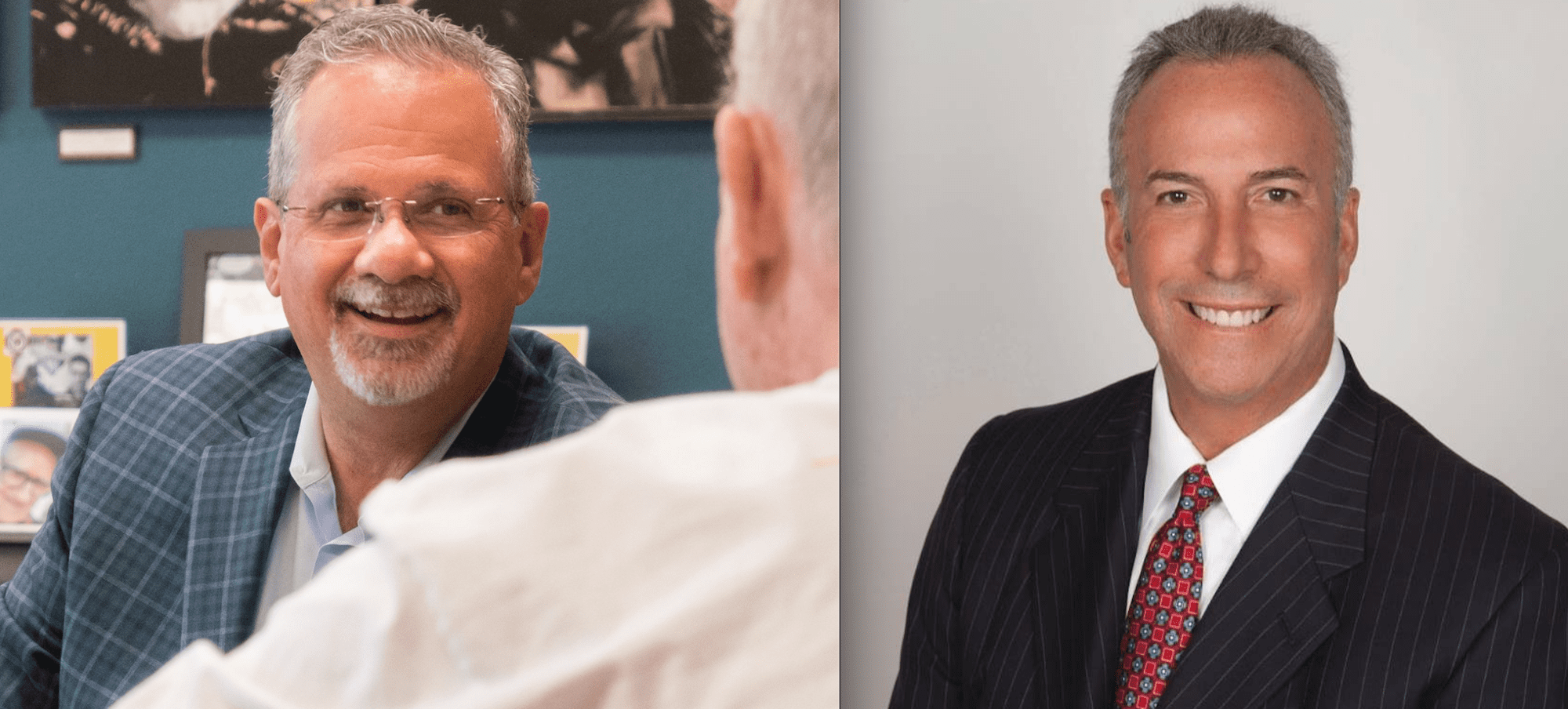

While the number of death sentences has fallen significantly in the United States, Las Vegas continues to frequently impose them. That’s thanks largely to District Attorney Steve Wolfson, a Democrat who took office in 2012. During his tenure, Clark County has remained one of the nation’s top jurisdictions in terms of new death sentences. Last year, he and his deputies, two of whom are influential state Senators, also helped kill legislation to abolish the death penalty in Nevada.

This year, Wolfson faces a primary challenger who vows to help end capital punishment in the state. Ozzie Fumo, a criminal defense attorney and former Nevada State Assembly member who introduced legislation to abolish the death penalty in 2019, is Wolfson’s only challenger so far in the June Democratic primary for DA in Clark County.

Fumo told Bolts he would never seek death sentences if elected. He also said he will continue to push for lawmakers to abolish capital punishment in Nevada, citing its disproportionate use against people of color and high fiscal impact.

“In my experience, the darker your skin, the more likely a person is to receive the death penalty,” Fumo said. “I would not seek the death penalty as district attorney of Clark County.”

This is the first time Fumo has taken this stance on how he would use his discretion as DA. In the past, candidates who say they personally oppose the death penalty have often stopped short of saying they would rule out its use within their office so long as capital punishment remains legal.

If Clark County were to shut the door to the death penalty, it would mark a major shift in the scope of capital punishment in the United States. According to data compiled by the Death Penalty Information Center, only three counties elsewhere in the nation have sentenced more people to death over the last decade.

The Clark County DA race is a window into the tensions at the heart of the modern death penalty in the United States. Executions and new death sentences continued a years-long downward trend in 2021, as even some conservative law enforcement officials, such as Utah County Attorney David Leavitt, turned away from its use. Yet at the same time, the practice has become more extreme and entrenched where it remains in use.

In 2021, Arizona refurbished its out-of-use gas chamber for potential use in future executions, while South Carolina authorized use of the electric chair as an execution method. Oklahoma has vowed to continue lethal injections even after last October’s execution of John Marion Grant led to him vomiting and convulsing while strapped to the gurney. Grant’s lethal injection was Oklahoma’s first since 2015, when other botched executions triggered a years-long pause.

Nevada almost swung in the other direction, in part due to legislation that Fumo pushed to abolish the death penalty while he was in the legislature. But those legislative efforts fell short, and Wolfson was key to preserving the death penalty in Nevada statutes. With Clark County comprising over 70 percent of Nevada’s population, he is one of the state’s most influential voices on criminal justice policy, repeatedly using his bully pulpit to oppose repeal. Last year, Wolfson testified against a death-penalty abolition bill, while two staff prosecutors who work for his office and also serve as state Senators—Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro and Senator Melanie Scheible—helped block the bill from inside the legislature. Having employees of the DA’s office in legislative leadership dims the prospects of criminal justice reform legislation beyond the death penalty, said criminal defense attorney Lisa Rasmussen.

“Nicole Cannizzaro has told me, ‘I am a prosecutor; I’m not going to vote for that,’” Rasmussen said of reform bills she has lobbied for at the legislature, including the bill to end the death penalty. “It feels like the criminal justice reform bills that she doesn’t want to have a hearing on don’t get a hearing.” Wolfson, Scheible and Cannizzaro did not respond to requests for comment.

Usual conventions of how prosecutors approach the death penalty may be changing, though. In 2018, when Wolfson was last up for election, he received a primary challenge from criminal defense attorney Robert Langford, who also sought to make an issue of the incumbent’s use of the death penalty. But Langford only said he would scale back its use, rather than ending it entirely. Since that time, it has become more common for prosecutorial candidates to say they would outright rule out seeking death sentences, as Fumo is now doing.

But Fumo did not lay out a plan to prevent staff prosecutors in his office from tanking the prospects of repeal in the legislature. The lawyers of a man currently on death row in Nevada are alleging in a lawsuit that Cannizzaro and Scheible violated conflict-of-interest rules during the debate over abolition last year because their role as lawmakers clashed with their jobs as deputy DAs. “If the Supreme Court says they can, I’m not going to prevent anybody from doing something they want to do,” Fumo said in response. He also said he would be willing to return to the state capitol to testify in favor of a bill abolishing the death penalty.

Nevada’s application of the death penalty is particularly prone to error. Between 2014 and 2017, for instance, the Nevada Supreme Court reversed three death penalty convictions and ordered new trials after finding racial discrimination in the jury selection process.

There are also racial disparities in how prosecutors apply the death penalty. According to numbers compiled by public defender Scott Coffee, defendants were Black in over 50 percent of cases where Wolfson signaled his intent to seek death sentences. Clark County’s population, by comparison, is 13 percent Black.

Nevada’s death penalty is also expensive to pursue relative even to life imprisonment, as is the case in other states where the question has been studied. A 2014 study commissioned by the Nevada legislature found that death penalty cases can cost up to $500,000 more than an identical case where a death sentence is not pursued. These costs mainly come from the stringent requirements surrounding capital cases, which obligate the defense to pursue extensive background investigation, mitigation efforts, and appeals.

Most defendants facing the death penalty are represented by public defenders, meaning the costs are borne by Clark County’s taxpayers. For a county that seeks multiple death sentences a year, these costs add up. “The county will see in the first four years how much money we will save based on my decision not to file the death penalty,” Fumo said.

Fumo says he would still pursue harsh punishments and that he would seek sentences up to and including life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. But taking the death penalty off the table could still change the balance of power between the prosecution and the defense. Even the threat of a death sentence is often enough to make defendants plead guilty in exchange for the DA not seeking capital punishment, according to Coffee, who noted that 83 of the roughly 120 death penalty cases resolved during Wolfson’s time in office resulted in pleas without going to trial.

“It’s a crowbar to drive negotiations,” Coffee added.

While Wolfson defeated Langford with 56 percent of the vote in the 2018 primary, the political ground in Clark County may have shifted in favor of criminal justice reform since then. In 2020, seven public defenders, all of them women, won elections to judgeships in Clark County, despite significant fundraising disadvantages, even as Fumo lost a statewide bid for a Supreme Court seat. (In the wake of the public defenders’ wins, Wolfson called for Nevada to replace judicial elections with an appointment system.)

Though Clark County hands down a large number of death sentences, executions in Nevada haven’t occurred since 2006. That could soon change, however, with Wolfson seeking to proceed with the execution of Zane Floyd, who in 2000 was convicted on four counts of murder, as well as sexual assault and other charges, and sentenced to death. The state’s supply of drugs that it plans to use in a lethal injection will expire at the end of February and may be difficult to replace—many pharmaceutical companies block prisons from purchasing drugs for use in executions.

Floyd’s lawyers have continued to appeal his death sentence, which Wolfson’s deputies have fought to uphold. Fumo said he believes that Floyd “deserves to spend the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of parole,” but would not seek to execute him.

“They can’t even get the medicine they need to do it correctly. Doctors and pharmaceutical companies are against it and refuse to sell those drugs to the state of Nevada,” Fumo said. “Look at all the wasted time and energy of the deputy district attorneys. They could be spending that time and effort into expanding programs or trying cases.”

It is unknown when Floyd’s execution would be scheduled if his appeals fail, and whether it would occur before a new DA came into office, and advocates say they are looking at many avenues. “We hope that the board of pardons, and the governor, and the attorney general, will hear Zane Floyd’s plea for clemency,” said Mark Bettencourt, project director of the Nevada Coalition Against the Death Penalty.