Republicans Add New Barriers to Oklahoma’s Dizzyingly Fast Process for Citizen Initiatives

A new law adds to a string of GOP-run states that have undercut direct democracy by piling on onerous new regulations and raising the threshold for signatures.

| June 17, 2025

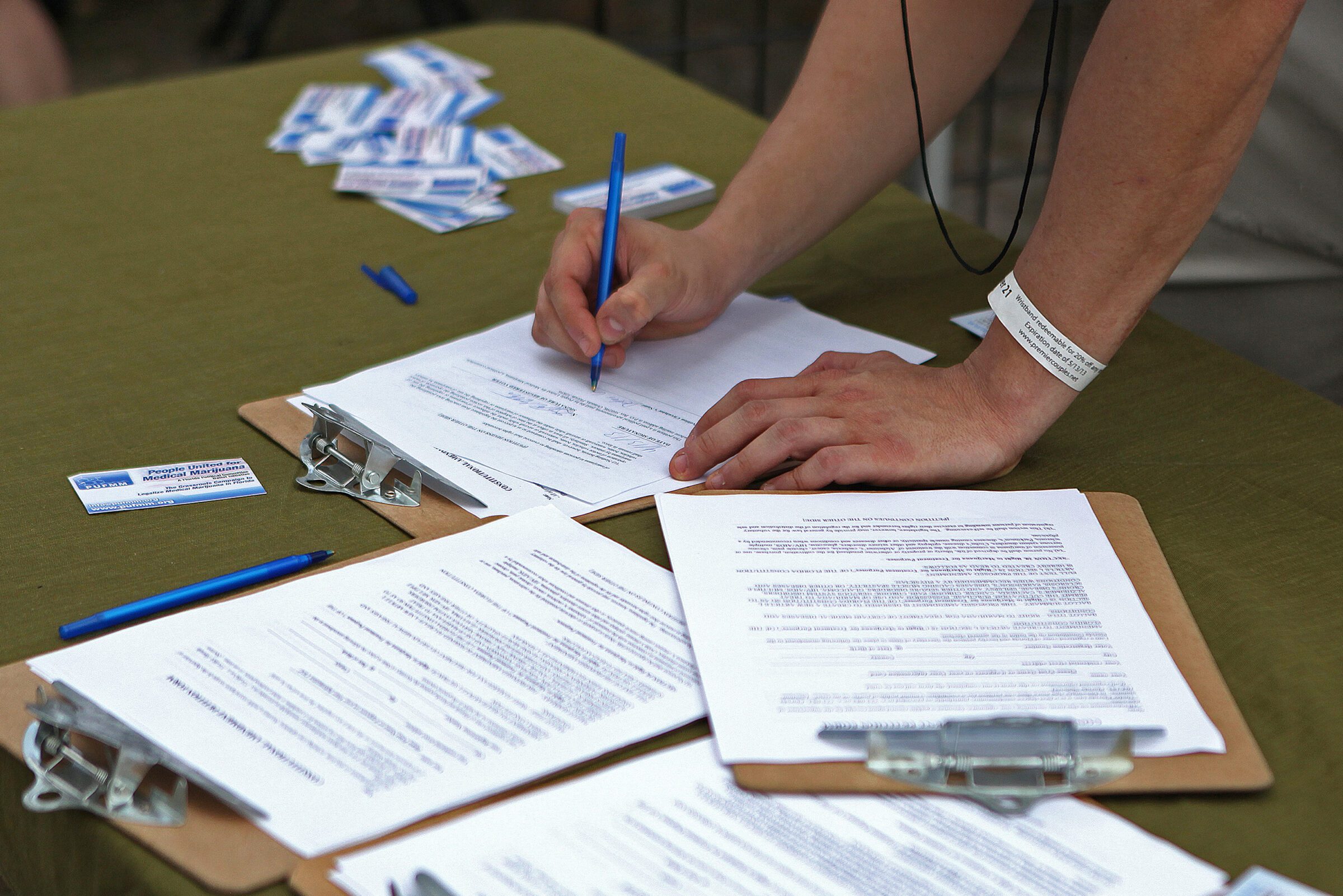

In Oklahoma, organizers have to race against the clock to get measures on the ballot.

The state has the nation’s shortest window of time for collecting the tens of thousands of signatures needed to qualify citizen-led measures—just 90 days, compared to other states with ballot initiatives, which all give canvassers 180 days or more.

Oklahoma’s 90-day sprint is about to get a lot rougher, thanks to a new law adopted by state Republicans late last month that piles on new regulations.

The law, Senate Bill 1027, caps the number of signatures that a campaign can secure in any given county, which will force organizers for ballot initiatives to spread themselves more thinly across the whole state instead of scaling up canvassing in more populous areas.

“You combine the 90-day period with these restrictive caps by county, you can understand why it will be nearly impossible to navigate this process,” said Amber England, a consultant who has shepherded many initiatives in Oklahoma and is now advising a campaign to boost the minimum wage that has already qualified to be on next year’s ballot.

Cindy Alexander, who trains volunteers on how to collect signatures as co-leader of Indivisible Oklahoma, shares England’s concern. “It is as difficult as it could be, and SB 1027 will make it even more difficult and more expensive,” she told Bolts. To meet this new requirement, she said, “We just need more than 90 days. That window is so short that it just makes logistical sense to go where the people are.”

Proponents of the new cap on signatures say it’ll empower rural areas and prevent campaigns from piling on signatures in population centers—in order to, in the words of GOP state Senator David Bullard, who sponsored the bill, “give more Oklahomans, not just the urban elites in Oklahoma City and Tulsa, a say in what questions qualify for the ballot.”

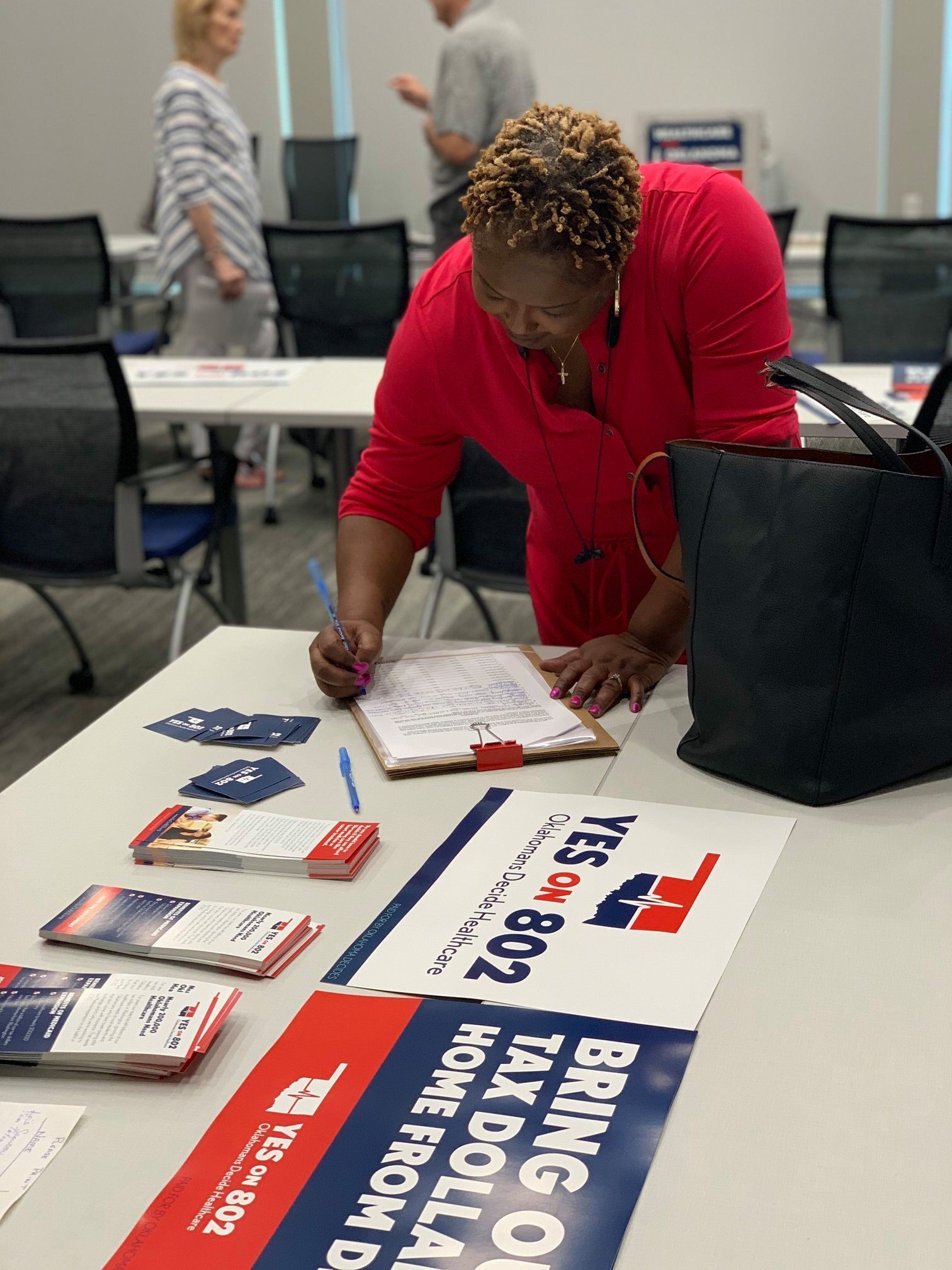

But critics warn that the new law will kneecap organizing everywhere. Say a proposal has a strong base of support in Atoka County, a sparsely populated area in Bullard’s district; under the new law, which caps petition signatures at 11.5 percent of votes cast during the last governor’s race for a statutory reform, such a petition could only submit a maximum of 450 signatures from Atoka County, even if many more people there support it. For Jed Green, director of Oklahomans for Responsible Cannabis Action, a group that’s working to qualify a measure legalizing recreational marijuana, these caps effectively block the voices of people who’d like to see a vote on a measure but whose support will never be counted; they “create two classes of citizens,” he said, “ones whose signatures can count and ones whose cannot.”

SB 1027 piles on other time-consuming provisions, like mandating that ballot campaigns file weekly reports about their finances. It also now requires anyone who signs a petition to attest that they’ve read its entire text, or had it read to them, which could balloon the time that canvassers must spend on each interaction.

Sign up to our newsletter

The legislation passed with heavy Republican support, though a handful of GOP lawmakers opposed it in the state House, and Republican Governor Kevin Stitt signed it into law on May 27. No Democratic lawmaker supported it.

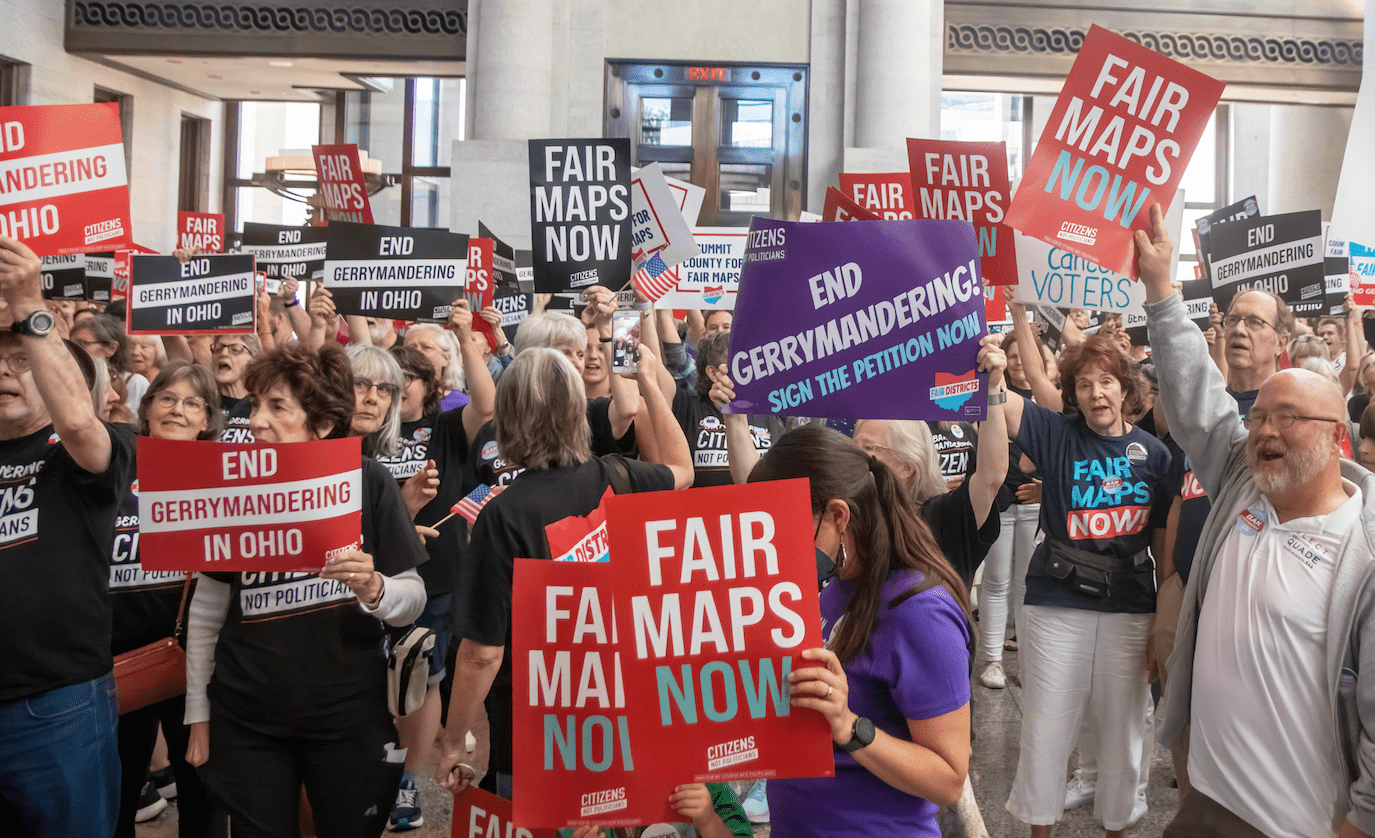

Its adoption added to the string of GOP-run states that have undercut direct democracy by piling on onerous new regulations and raising the threshold for signatures that organizers have to meet, including Arkansas and Florida earlier this year.

In many states, including Oklahoma, a false statement on a petition can trigger criminal charges, which advocates say can make people afraid to get involved in ballot initiatives. When Arkansas this spring adopted the same new requirement that’s in Oklahoma’s new law, that anyone who signs a petition must attest to having read it in full, the president of the Arkansas’ League of Women Voters told Bolts she didn’t even know how she’d train her team to enforce it. “What if the potential signer appeared to merely skim through the language?” she told Bolts earlier this year. “Are you supposed to question them? If you don’t and someone is watching/recording, then you’re on the hook for a crime.”

In adopting these new restrictions, conservative lawmakers have been vocal about their frustrations toward groups that have placed measures that they oppose on the ballot. In Oklahoma, voters over the last decade have expanded the state’s Medicaid program and lowered some criminal penalties. Next year, voters will choose whether to raise the state’s minimum wage, which is currently set at the federal minimum of $7.25.

Organizers in Oklahoma are also currently proposing another ballot measure to change the state’s election system: State Question 836, which would establish all-party primaries, from which the top two candidates would move on to the general election, regardless of their party affiliation. Oklahoma’s Republican Party filed a lawsuit against the proposal in April, which has blocked organizers from collecting signatures for now.

Margaret Kobos, founder of Oklahoma United, a group that’s championing this new system, says traditional election rules make for uncompetitive and sleepy general elections since Oklahoma is currently a “one-party state,” and that the changes would “give people choices and get more people engaged.” Any reform to really shake up Oklahoma’s status quo would only be able to succeed through the ballot initiative route, which is why she’s so concerned by SB 1027, telling Bolts that it “throttles the voices of citizens.”

“The citizen petition is really our only way to effect a systemic change in Oklahoma, and that’s what our goal is,” Kobos said.

A group of Oklahomans, including several supporters of State Question 836, filed a lawsuit last week in state court arguing that vast swaths of the new law are unconstitutional and subject Oklahomans to an “undue burden.”

The law “imposes insurmountable logistical burdens, massively inflates costs, and prevents both rural and urban proponents from gathering the required number of signatures within the 90-day circulation period,” the lawsuit argues. “It suppresses citizen lawmaking altogether.”

The lawsuit claims the language in SB 1027 is so strict that it actually bars people from signing a petition once a county cap is reached—as opposed to just tossing or ignoring signatures over the cap. This would create an insurmountable obstacle, the lawsuit argues, because ballot campaigns always need to secure extra signatures to build a buffer in case some signatures are ruled to be invalid.

Bullard, the senator who sponsored the bill during the legislative debates this spring, did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Lonnie Paxton, the Republican senator who initially filed the bill in February.

The lawsuit also takes issue with the fact that SB 1027 gives the secretary of state new powers to review and potentially block proposed measures, a role that the state supreme court has historically played—which the suit says “usurps judicial functions and erects unconstitutional executive-branch gatekeeping.”

Oklahoma’s secretary of state is appointed by the governor; Stitt named Josh Cockroft, who’d recently worked as the political director of his reelection campaign, to the job in 2023.

Critics of the law say this provision gives state officials too much leeway to stall measures they personally oppose. “This is the way for them to exert control over the process and to do whatever they can to either make it easier or make it harder for a campaign to be successful,” said Andy Moore, CEO of Let’s Fix This, an organization that promotes civic engagement in Oklahoma. Moore called the new powers given to the secretary of state to block ballot initiatives “a clear insertion of partisan politics into the process that shouldn’t be there.”

In other states that already give a similar power of review to state officials, some attorneys general and secretaries of state have used that authority to stonewall proposals on abortion rights, voting rights, and government transparency. Some Oklahoma advocates are now bracing for a repeat in their own state.

That’s in part because Oklahoma officials already have a history of toying with the timing of initiatives. For instance, Stitt, who has wide latitude over when an initiative appears on the ballot, decided last fall to wait until mid-2026 to hold the referendum to increase the minimum wage, frustrating the campaign’s organizers who did not want to wait that long.

In 2023, Stitt had scheduled an earlier measure to legalize marijuana on a day in March with no other elections, creating a confusing schedule of three separate election days in a two-month stretch—which proponents of the legalization initiative say led to its defeat in a very low-turnout election. “Doing it like this was clearly a way to suppress turnout,” Moore told Bolts at the time. Now he worries SB 1027, which doesn’t even specify a deadline for the secretary of state to review initiatives, will exacerbate such gamesmanship and allow officials to drag out the process.

By contrast, canvassers have to be ready to jump into action as soon as state officials greenlight a proposal, with no clear timeline or advance warning, since that immediately starts the clock on the 90-day deadline. “How do you mount a campaign effort? How do you pay staff?” Moore said. “How do you do all this stuff when you don’t have any idea of how long it’s gonna take?”

Alexander, the Oklahoma Indivisible co-leader, says these complications are already often too much for grassroots organizations like hers. No abortion rights initiative has gotten off the ground in Oklahoma, unlike in many other states, with supporters withdrawing a proposal in late 2022 because they did not think they could pull it off in 90 days.

Still, some other issues in the state have generated enough support, energy and funding to get past those logistical hurdles, Alexander says—at least until SB 1027. “There were a series of things where the legislature failed to act, and people took it upon themselves to go to the ballot,” she said. “That collective work has likely frustrated lawmakers in power because they want to keep power for themselves.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.