Pennsylvania Reckons with Its Draconian Laws on Life Imprisonment

Over 1,000 Pennsylvanians are serving life without parole sentences for murders they didn’t themselves commit. The state supreme court agreed to review whether this is constitutional.

Victoria Law | March 12, 2024

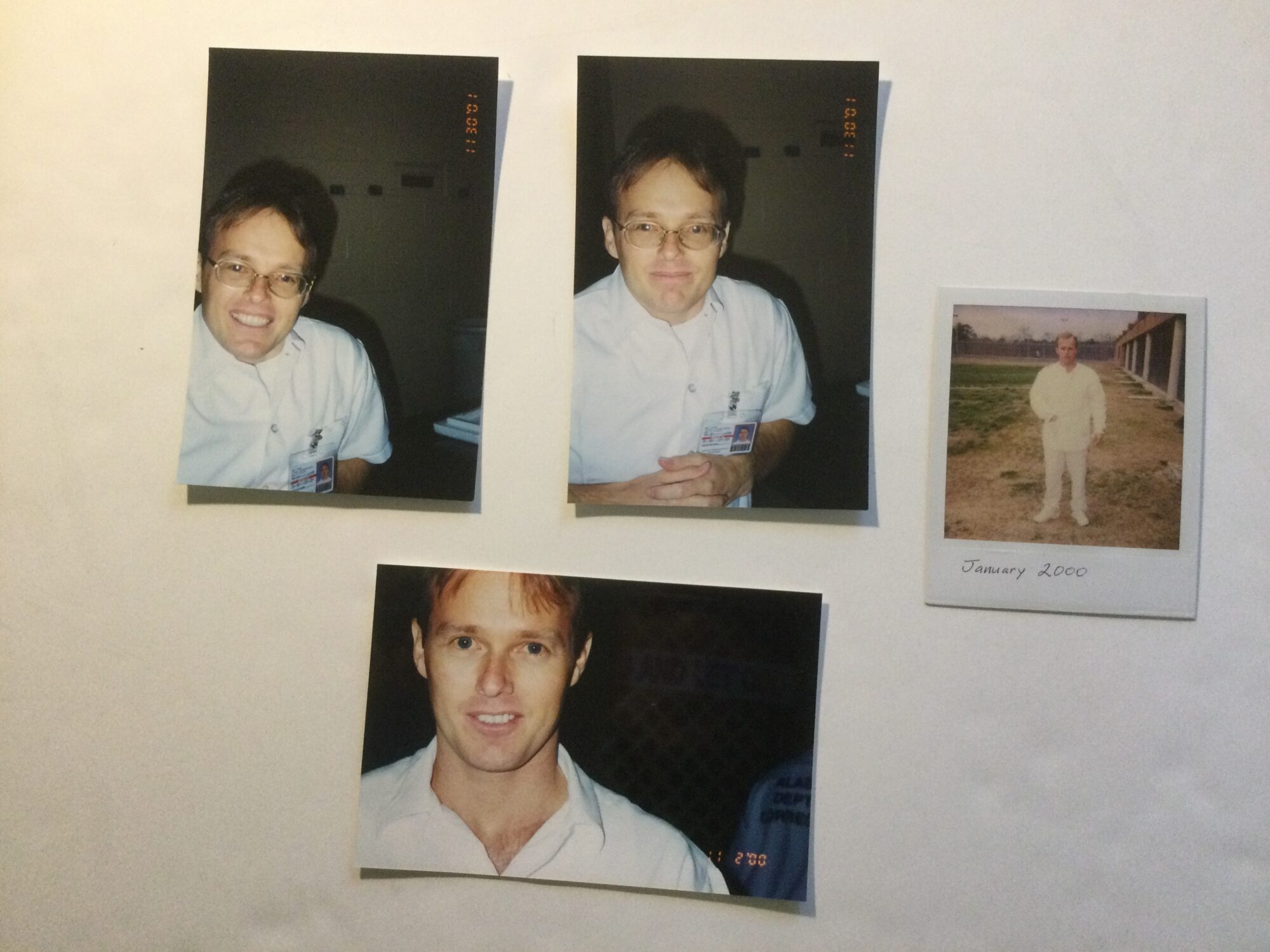

Derek Lee thought he might spend the rest of his life fighting to get out of prison for a murder he didn’t commit. “I had to draw strength from God to keep fighting and believing,” he told Bolts in an email, recalling his dread when the pandemic shut down programs in his prison. He retained some access to the law library, though, and connected with new outside lawyers to challenge the constitutionality of his sentence of life without the possibility of parole for felony murder.

Lee received a ray of hope last month when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court agreed to hear his appeal.

What the justices decide might ultimately give 1,100 others a chance at freedom as well. The case, which the court will hear later this year, marks a potential turning point for a state that’s exceptionally punitive by national standards in handing out life without parole sentences.

“With the recent development at the supreme court,” Lee told Bolts in an email last week, “many ppl have been sharing with me how this possibility has restored a [sense] of hope in their life to have another chance at freedom.”

In 2014, Lee, then age 29, participated in a burglary in which his accomplice fatally shot the homeowner. Lee had not been involved in the killing and wasn’t even in the room at the time. Nonetheless, two years later, he was convicted of felony murder, a type of charge that prosecutors can bring against someone who was involved in a crime that led to a death, even if the death was unintentional or the defendant didn’t participate in the killing.

In Pennsylvania, felony murder is classified as second-degree murder, and all convictions for second-degree murder trigger an automatic sentence of life without parole. These abnormally draconian laws have made Pennsylvania home to near-record numbers of people sentenced to die in prison. The state has the second-highest number of people serving life without parole, nearly 5,100 people; approximately one in five have been convicted of felony murder.

“There are so many other individuals who have [served] so much more time. I hope that they will finally have that opportunity to go back into society and have a positive effect,” Lee told Bolts in an earlier exchange. “It’s easy for us to throw people away. But if somebody is putting in the work to truly transform and can be useful to society, families and communities, then why not use that person? I believe in redemption if somebody has done the work.”

Lee’s appeal argues that his sentence violates the state constitution, which prohibits “cruel punishment.” This wording is different than the federal constitution’s Eighth Amendment, which bans punishment that is “cruel and unusual.” Since some 1,100 people are sentenced to life without parole for felony murder in Pennsylvania, the punishment may not be considered unusual within the state, but Lee’s appeal argues that it is nonetheless cruel to automatically condemn someone to die in prison for a killing they didn’t commit.

Other state constitutions have similar language against “cruel” punishments; their courts have used those clauses to issue protections that go beyond those afforded by federal courts.

Still, Lee’s appeal is making the case that his sentence also violates the federal constitution. His brief states that Pennsylvania’s statutes are “out of step” with contemporary standards, making them unusually punitive in violation of the federal constitution. Pennsylvania is the only state besides Louisiana that mandates life without parole for second-degree murder.

Pennsylvania’s superior court, the lower court that handles criminal cases, rejected Lee’s appeal in June, ruling that it was bound by precedent to reject his plea. But one of the judges, Alice Dubow, called on the supreme court to take up the case and revisit the question of whether automatic life without parole sentences for second-degree murder violate Pennsylvania’s state constitution. Dubow is a Democrat, as are five of the seven justices on the supreme court, though partisanship is often not a strong predictor of how judges settle criminal justice matters.

Life without parole has frequently been proposed as a more humane alternative to the death penalty, but advocates for reform call it “death by incarceration.” Ashley Nellis, senior researcher with the Sentencing Project, points out that LWOP sentences allow for virtually no second chance no matter a person’s transformation or the amount of time that has elapsed.

“The state is killing you, just slower—and for a wider range of offenses or participation in those offenses,” she said.

Nellis points out that the expansion of life without parole has far outpaced the decline in the death penalty. The number of people serving life without parole has jumped 66 percent since her organization began collecting data in 2003, reaching roughly 56,000 people as of a 2021 report by the organization. In Texas, for instance, the number of life without parole sentences has grown as the number of those sentenced to death has dropped. “When you’re looking at a death sentence, you have a capital attorney and [other] special rights given to you because of the seriousness of the sentence,” Nellis noted, but those protections are not available to those facing LWOP.

Over the past decade, courts and lawmakers have begun to slowly reassess who can face such extreme sentences. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Miller v. Alabama that mandatory life sentences for children under age 18 were unconstitutional. Four years later, the court made its Miller decision retroactive, enabling thousands to apply for resentencing.

Since then, more than two dozen states have since outright banned sentences of life without parole for children. Some have also restricted life without parole for “emerging adults”, an acknowledgement of emerging research in neuroscience that shows people’s brains continue developing well into their mid-twenties. Massachusetts and Washington, D.C., have gone the furthest so far, effectively banning such sentences for people under age 21 and 25, respectively; in Massachusetts, the change came through a decision of the state supreme court earlier this year. Some lawmakers have also introduced legislation that would eliminate life without parole altogether, regardless of age.

In Pennsylvania, the provision to automatically sentence people to life without parole for second-degree murder already is a contentious issue. U.S. Senator John Fetterman tried to expand clemency for that population while he was lieutenant governor, and then faced attacks over that work when he ran for Senate in 2022. Last fall, Democratic lawmaker Tim Briggs announced legislation to end these automatic sentences, though he has yet to file it —the same demand that Lee is making through the legal route.

Lee remains determined not to die in prison. In 2016, the court assigned him an attorney to assist with his post-conviction appeal. In Pennsylvania, a person must file a notice for appeal within 30 days. That attorney filed nothing, leaving Lee barred from making any further appeals for the next five years. By 2020, when Lee successfully petitioned to reinstate his appeal rights, he had connected with attorneys from the Abolitionist Law Center, an organization that had already mounted several challenges to life without parole in the state. The center, along with the Amistad Law Project and the Center for Constitutional Rights, agreed to take on Lee’s appeal and, with it, mount another challenge to the state’s inclination for “death by incarceration.”

For Bret Grote, the lead attorney on Lee’s challenge and the Abolitionist Law Center’s legal director, a favorable ruling for Lee could have substantial implications for other states. “It could create momentum for legislative and judicial reform,” he told Bolts. “It could [also] provide a persuasive precedent of a state using its own constitution to provide greater protections than the federal constitution.”

Nellis agrees. These types of challenges on the state level could not only provide relief both retroactively and in future cases, but, she said, “continue to shed more and more light on the fact that this sentence is applied in arbitrary and very unfair ways.” A clear majority of people who serve life without parole sentences in Pennsylvania are Black, according to data compiled by the Sentencing Project.

Lee says he reconnected with his Christian faith behind bars, which gave him the strength to keep fighting his extreme sentence. He says he only has to glance around his cellblock to know that the court’s decision on his case could affect many more than just him.

“A lot of guys on the block are lifers with twenty, thirty years on their sentence,” he told Bolts. When they heard that the court would consider his appeal, hope rippled through the prison.

“This is the greatest news I’ve gotten in so long,” he recalled one man, who had been imprisoned for over 30 years, telling him.

“Your case is going to affect mine immediately,” another man, who had already served 26 years, told him.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.