The Unwritten Senate Rule Blocking New Jersey Governor’s Nominees

The governor’s nominee for the state supreme court has not been seated for more than a year over the objections of a Republican senator.

| April 13, 2022

The article is published through a collaboration between Bolts and the New Jersey Monitor.

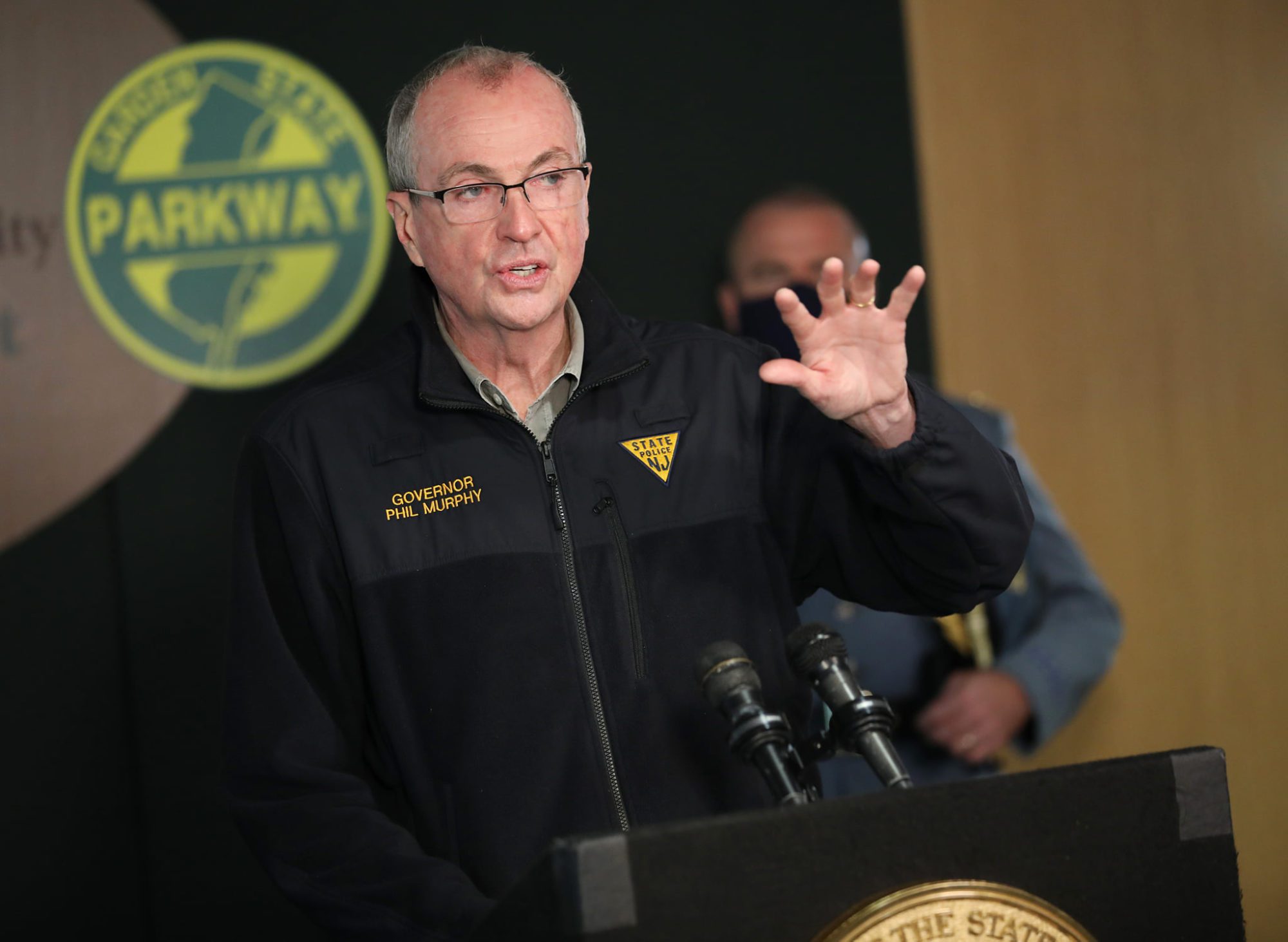

An unwritten rule that gives state senators virtual veto powers over gubernatorial nominees has stalled the confirmation for months or longer of top state officials nominated by Democratic Governor Phil Murphy.

Tahesha Way was renominated as secretary of state in January but lawmakers have not considered her nomination yet. There’s been no movement on acting Education Commissioner Angelica Allen-McMillan’s nomination since October 2020. Murphy’s choice for attorney general, Matt Platkin, appears headed for a similar fate.

And Rachel Wainer Apter, a former advocate with the ACLU who is Murphy’s pick for the New Jersey Supreme Court, has awaited a hearing for more than a year. And unlike non-judicial appointees, Wainer Apter cannot be seated unless her nomination goes before the full Senate. A supreme court decision against expanding the rights of defendants last month may have gone the other way had she been on the court.

Each of these nominations has run into an immovable roadblock: senatorial courtesy. The rule, which appears nowhere in New Jersey’s constitution, state law, or legislative rules, allows upper-chamber lawmakers to indefinitely block nominees from their home counties or who live in their districts. Senators don’t have to give a reason—and they often don’t.

“No governor likes senatorial courtesy, and every senator loves it,” then-Governor Chris Christie, a Republican, said in 2011.

In the cases of Way, Allen-McMillan, and Wainer Apter, two Republican senators have blocked the appointments despite Democrats’ majority in the chamber. A Democrat is behind the delay on Platkin’s nomination.

The practice is similar to one in the U.S. Senate, where court nominees can be blocked if either of their home state senators does not return what’s known as a “blue slip,” a piece of paper indicating the senator supports the nominee. Most recently, Republican Senator Ron Johnson of Wisconsin used the “blue slip” tradition to block the appointment of a federal judge in his state.

In Congress, the tradition has grown into a source of controversy. Republican leaders disregarded some absent slips by Democratic senators during the Trump administration, and now some Democrats who associate it with counter-majoritarian mechanisms like the filibuster that most of their party has come to oppose are demanding that it be done away with.

Those demands are largely not present in New Jersey. And despite national Democrats’ anger toward Republican refusal to move forward on former President Barack Obama’s nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court, Merrick Garland, there is no parallel firestorm in New Jersey over a Republican senator forcing a vacancy on the state Supreme Court.

New Jersey’s unwritten rule exists at the pleasure of the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee and, ultimately, the Senate president, both of whom are Democrats. Lawmakers could approve legislation or rules changes to bar the practice.

Nicholas Scutari, the chamber’s Democratic president and the former longtime chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, declined to comment through a spokesperson.

New Jersey governors have expressed mixed feelings about senatorial courtesy. Murphy has said he supports it. Christie didn’t nominate judges in Essex County as punishment for two of the county’s senators invoking senatorial courtesy for one of his nominees. Brendan Byrne in 2004 criticized its “abusive use.” And Tom Kean Sr. cautioned the practice empowers interest groups to stall the appointments of regulators and enables “government by corruption.”

Though officials and advocates occasionally rail against individual senators who have invoked courtesy to block a nomination, there is no formal campaign to do away with the practice.

Even groups like the New Jersey State Bar Association, which decades ago backed a constitutional amendment that would have required the Senate to vote on gubernatorial nominations within 90 days, have backed away from advocating against senatorial courtesy.

“For the most part, the system’s worked,” said Domenick Carmagnola, president of the State Bar Association. “I’m not a big believer, and the state bar’s not a big believer, in ‘let’s look at a major overhaul because of an exceptional circumstance if, for the most part, it’s worked.'”

He added any effort to do away with courtesy would likely fail to gain traction in the Legislature.

Courtesy is the greatest source of individual power for most of New Jersey’s senators. Legislators have—and continue to—use courtesy as a bargaining chip to win nominations for political allies, legislative concessions, or funds for pet projects. The late Senator Anthony Bucco used it in 2004 to force a meeting between himself and the state’s environmental protection commissioner.

Republican Senators Kristin Corrado, who represents Passaic County and has courtesy over the nominations of Allen-McMillan and Way, and Holly Schepis, who represents Bergen County has so far blocked Wainer Apter’s confirmation, did not return calls seeking comment.

Schepisi has previously said she was withholding courtesy to ensure New Jersey’s high court maintains its tradition of partisan balance.

The delay in confirming Wainer Apter has created a vacant seat on New Jersey’s high court, which now has just six members instead of its usual seven.

Chief Justice Stuart Rabner appointed Judge Jose Fuentes on a temporary basis in December to fill the seat that Murphy named Wainer Apter for. But after Justice Faustino Fernandez-Vina stepped down upon hitting the mandatory retirement age of 70 in February, Rabner said he will not make an interim appointment for Fernandez-Vina’s seat because the next judge in line for the appointment is a Democrat whose elevation would disturb the court’s partisan balance. (The Murphy administration is not naming someone to fill this new vacancy until Wainer Apter’s nomination is heard by the Senate.)

So far, the vacancy has only led to one Supreme Court ruling that might have gone a different way if the court had seven judges. In a 3-2 decision from March, justices reversed a lower court ruling that would have expanded Miranda rights for people accused of crimes. Two of the court’s three Democratic-appointed justices dissented, warning that the decision will “erode faith in our criminal justice system.”

If Wainer Apter had taken part in this case and sided with the two dissenters, the resulting tie would have left the lower court’s ruling in place.

In Platkin’s case, Democratic Senator Dick Codey has invoked courtesy. Codey declined to say why.

When asked about it last week, Codey said, “Next question.”

For officials who are appointed to executive positions like Way and Allen-McMillan, a delayed confirmation by the Senate changes little. Holding the position in an acting capacity puts no limits on their authority. But for people appointed to judgeships, state boards, and similar bodies, senatorial courtesy is consequential since they must be confirmed to take their posts.

Stalled nominees for New Jersey posts with lax residency requirements can also skirt the rule by moving to a different county or legislative district, though the sprawling nature of some legislative districts means some would have to move far. Corrado, for example, has courtesy over all of her home county of Passaic and 12 towns in Bergen, Morris, and Essex counties.

Before New Jersey adopted its 40-district legislative map in 1966, legislators only had courtesy over nominees from their home counties.

There are other ways for senators to delay or kill nominations.

The Senate president and the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee—Democratic Senator Brian Stack is the panel’s current chairman—can withhold a committee hearing or floor vote.

Former Senate President Steve Sweeney kept the nomination of New Jersey State Police Superintendent Pat Callahan in limbo for more than two years with no invocation of courtesy (Callahan lives in Warren County, Sweeney in Gloucester). The Senate unanimously confirmed Callahan in December, after Sweeney lost re-election and shortly before Scutari replaced him as the Senate president.

Murphy, who stands to gain the most from the rule’s removal, isn’t pressing for courtesy reforms. A spokesperson for the governor declined to comment on the rule’s continued existence, deferring to comments the governor made last May.

“I have to say my bias, just being asked it for the first time, is it’s a rightful element of a balance of power, even where it may frustrate you one day or another,” Murphy said at the time. “At the end of the day, I think the notion of having the equal branches of government exercising their rights is, I think, a good thing.”