Utah Was a Rare Red State to Champion Mail Voting. That Era Is Ending.

Inspired by the architects of Project 2025, Utah adopted a Republican bill to end universal mail voting and impose new restrictions on absentee ballots.

| March 12, 2025

Editor’s note: The Utah governor signed House Bill 300 into law on March 26.

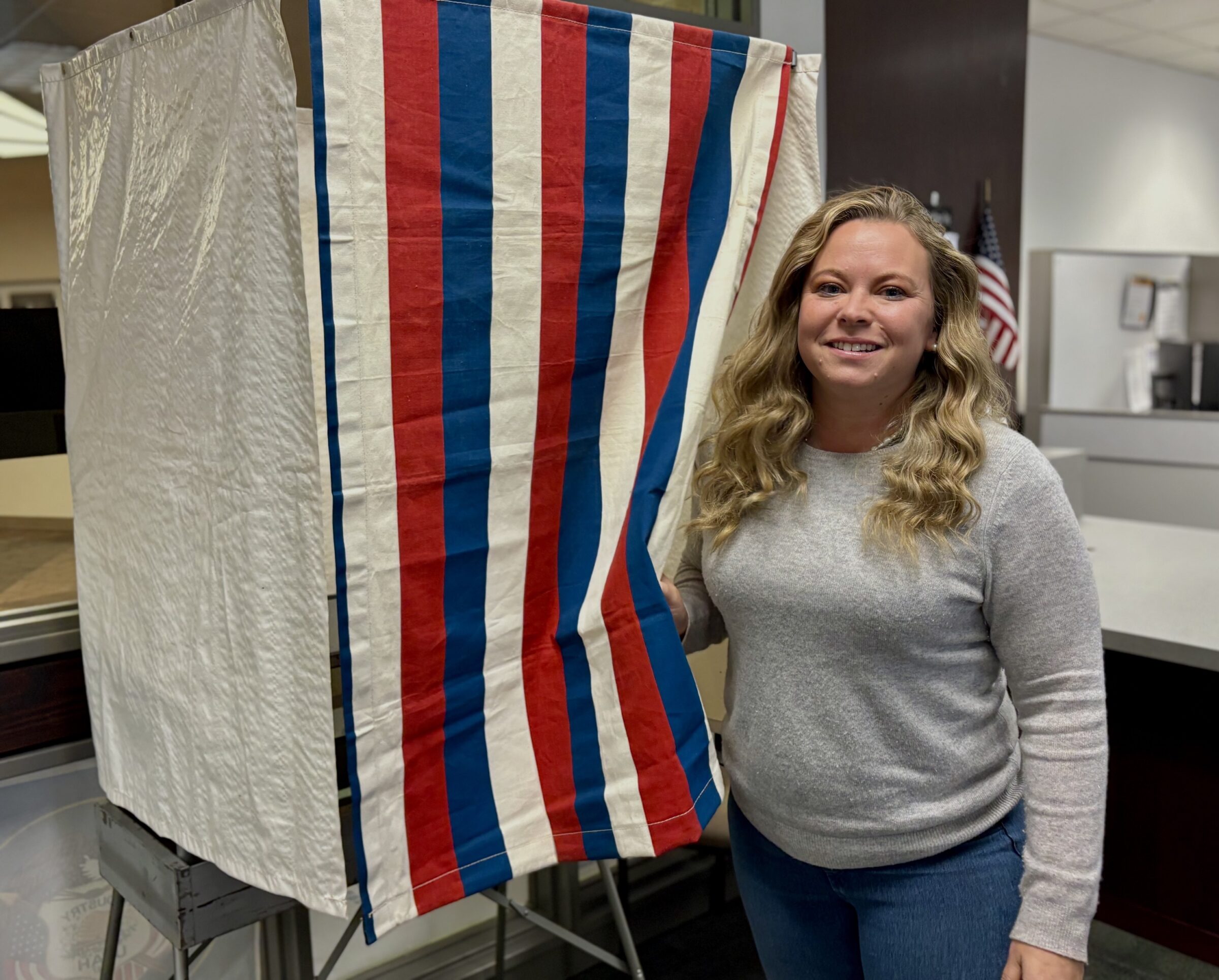

An old-fashioned, four-legged polling booth is on display in the lobby of the Salt Lake County clerk’s office. Its metal frame roughened and its red, white, and blue privacy curtain wrinkled, it’s a reminder of what voting in Utah looked like in the time before drop boxes for mail ballots and computerized tabulators.

Lannie Chapman, the county clerk who runs this office and serves as the top elections official in Utah’s most populous county, eyed the artifact and considered how different, and difficult, her work would be if the state ever went back to voting the way it did when the old booth was in use.

“No, thank you,” she said at the prospect, laughing. “It’s fun for a photo op, but that’s about it.”

The hypothetical may be a bit too close for comfort. A few miles up the road from Chapman’s Salt Lake City office, at the Utah State Capitol, lawmakers have just put the finishing touches on a major voting-system overhaul: House Bill 300, which passed the Republican-controlled legislature March 6, would end universal vote-by-mail in Utah.

It’s a landmark reform that would close an era in which Utah occupied a unique place in the national patchwork of election rules: Since 2019, it’s been the only reliably red state in the country to automatically mail a ballot to every registered voter.

HB 300 would instead require any Utah voter to proactively request a mail ballot. It would also impose additional restrictions on how they must return these ballots, for instance by ending the grace period for when they must be delivered to election offices by postal workers.

“We are known for safe, secure, and convenient access, and this is going to make everything a lot more difficult,” Chapman said. “It’s not fair to our voters.”

Today, more than nine out of 10 Utahns vote by mail, and the option has been an especially valued convenience for rural voters who live far from polling places. But Donald Trump’s false claims that mail ballots are responsible for widespread fraud have largely turned conservative politicians against mail voting since 2020, and that rhetoric has now caught up even with this state.

The bill passed the legislature mostly on party lines, with five GOP lawmakers joining all Democrats in opposing it, and now awaits the signature of Republican Governor Spencer Cox. (Update: The governor signed the bill on March 26.)

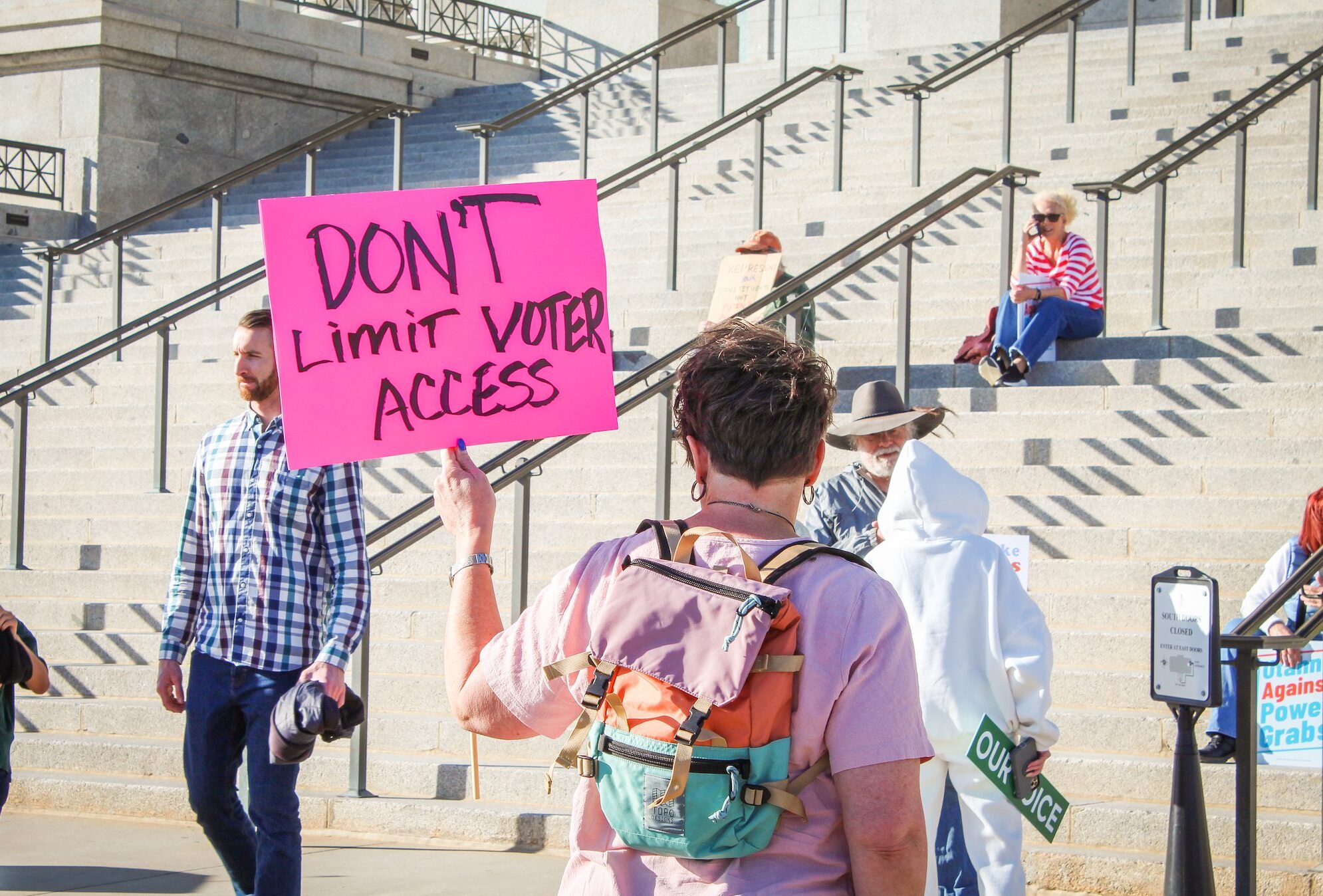

Chapman and dozens of other officials and voting rights advocates rallied at the Utah State Capitol on Monday to condemn the bill and urge Cox to veto, though he has signaled clearly that he plans to sign it: He recently called the bill “brilliant,” praising its potential to “restore trust” in mail voting, according to the Associated Press. If he signs the bill, that would leave just seven states—California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Vermont and Washington—plus Washington, D.C., that automatically mail ballots to all registered voters.

Feverish negotiations over the last month did push the bill’s sponsors to delay implementation, such that universal vote-by-mail won’t end until 2029. This means that registered voters would still receive their ballots this way for another four years. But some of the bill’s other restrictions on mail voting would come into effect a lot sooner.

In addition to changing the rules on mail ballots, HB 300 would limit voter ID options for in-person voters, also by 2029.

In the run-up to HB 300’s passage, county clerks from both parties joined voting rights advocates in imploring lawmakers not to adopt major changes to a voting system that, by key measures, appears to be working quite well. Some of these critics were pleased to extract concessions but they remain concerned.

Ricky Hatch, the Republican clerk in Weber County, told Bolts after the bill’s passage last week that he has no doubt that the legislation will lower turnout by making the process of voting harder. “The question is how much,” he said.

“It is not a great bill,” said Brian McKenzie, the Republican clerk in Davis County. “I love vote-by-mail. It’s been very successful, and it’s worked very well in the state of Utah. Unfortunately, I’m not a policymaker.”

Added Chapman, a Democrat, “This is going to decrease participation.”

Universal vote-by-mail began in 2012 in Utah, when the state allowed counties to run elections entirely by mail if they so chose. The uptake was gradual, and by 2019, every county in the state was on board. This shift led to a dramatic increase in turnout, particularly in municipal and off-cycle elections, Brigham Young University researchers found.

This system has been associated with no significant fraud—a legislative audit released in December found just two improper votes among more than 2 million statewide in 2023 and 2024—and a poll released last month by the Sutherland Institute, a conservative Utah think tank, showed that 87 percent of Utah voters are “confident” their ballots are being counted accurately.

“It is tested and it is secure. People love voting this way,” said Ellie Menlove, an attorney with the ACLU of Utah. “We are at a loss for why the legislature is pursuing these changes.”

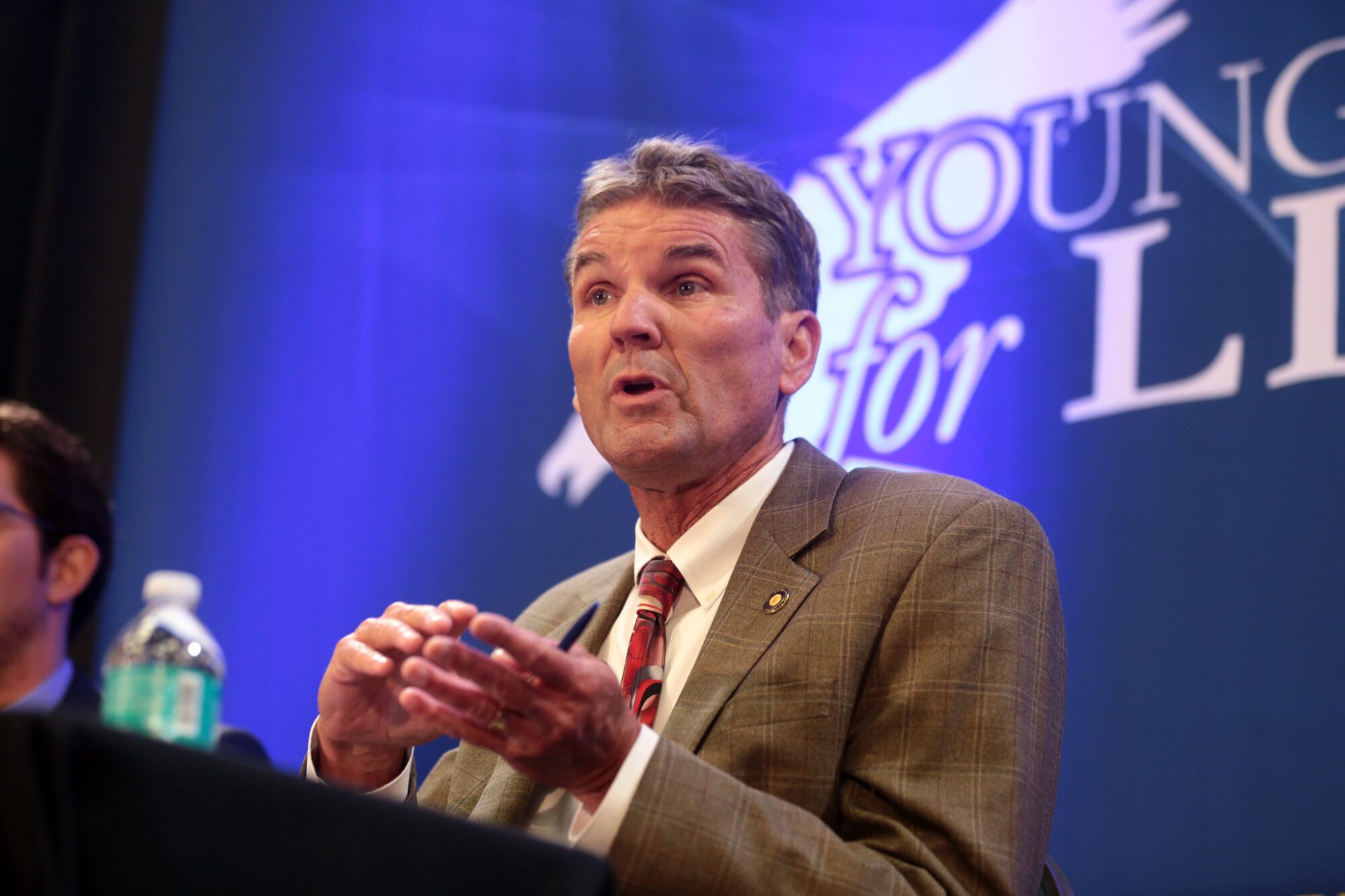

Bolts put the question to state Representative Jefferson Burton, the Republican lawmaker who championed the bill. Burton conceded that the audit found no widespread fraud in Utah, and that vote-by-mail has increased turnout.

But he cited an “Election Integrity Scorecard” by the Heritage Foundation, the influential national conservative think tank that published Project 2025, the right-wing blueprint for Donald Trump’s second term. The scorecard ranks Utah 33rd among all states and the District of Columbia, docking Utah significantly for its policies on voter ID and absentee balloting.

Burton said he expects that HB 300 will vault Utah into the list’s top 10, and made clear that he tailored his bill to that aim. “They [Heritage] think it should be a conscious decision for a voter to opt in to vote by mail,” he said. The lobbying arm of the Heritage Foundation, Heritage Action, has endorsed Burton’s bill.

The top 10 on The Heritage Foundation’s list are all red states that, in various ways and to various degrees, make voting much more difficult than Utah does, and generally have created high disparities in participation by race and by economic status. The top-ranked state on the list, Tennessee, has some of the nation’s harshest rules toward people with past criminal convictions, disenfranchising hundreds of thousands of would-be voters for life and blocking about one in five Black adults from voting. Its voter turnout rates are consistently among the lowest in the country.

“We shouldn’t want to be ranked high on this list,” Menlove said. “Nothing on the list shows whether your elections are secure; it’s all about whether you make it hard to vote.”

Project 2025 specifically calls out “mail-in ballot fraud” as a problem the Trump administration should prosecute aggressively. The president has argued consistently and without evidence that such fraud is rampant, and the first two months of his term have brought fears that he may attempt a takeover of the U.S. Postal Service, which could affect mail delivery. Since the 2020 election, many GOP-run states, such as Alabama and Georgia, have already moved to limit mail voting, including by restricting or outright banning ballot drop boxes, and by moving up deadlines to request or return mail ballots.

The original version of HB 300 proposed even more dramatic changes than those that passed last week: Burton’s initial bill would have effectively ended vote-by-mail entirely, by requiring voters to return absentee ballots in person. They would have had to show up, with photo ID, to county offices; this step would have meant multiple hours of driving for some rural voters.

Voting rights advocates and county clerks fought Burton’s initial proposal for weeks, rallying even some Republican lawmakers, and GOP leaders ended up watering down the legislation. Under the bill that actually passed the legislature last week, voters retain the ability to request absentee ballots and mail them back.

Voters who opt in would receive mail ballots automatically for a period of eight years. But they would be removed from that list if they miss two consecutive general elections. The bill also requires that anyone who casts a mail ballot write on it the last four digits of a government-issued driver’s license or state identification card, starting in 2026, while allowing for some alternatives if voters do not have one of these IDs.

The bill also immediately ends Utah’s grace period for mail ballots. Counties to this point have been allowed to count mail ballots that are postmarked by 8 p.m. on Election Day, even if they arrive at election offices in the hours or days following that deadline. But under HB 300, counties will only be able to count the ballots they receive by 8 p.m. on Election Day, meaning that voters will need to mail their ballots well before then.

Chapman worries that some ballots will be rejected under HB 300’s new cutoff. “Like our voters that are in college out east, who are mailing their ballot back here,” she said. “I might not get their ballots on election night, even if they mailed it a week before.”

Burton brushes aside predictions that these changes will present new hurdles for voters and lower turnout. “We want people to vote who have demonstrated they’re citizens and that they’re eligible to vote,” he said. “We don’t want to disincentivize anybody.”

If and when Cox signs the bill into law, he will kick off a mad scramble by voting rights advocates and election administrators to educate voters about these changes before the bill’s 2029 effective date. Burton’s bill calls for $2 million in funding for public education in 2026; he has suggested the state could use some of that money to rent billboard space advertising the changes.

“The $2 million fiscal note doesn’t even cover my county’s portion of the ramifications,” said Chapman, the Salt Lake County clerk who represents about a third of Utah’s total population.

“We are going to have to work our tails off,” said Hatch, the clerk in Weber County. Still, Hatch credits Burton and other GOP sponsors of HB 300 for listening to some of his biggest concerns and he is glad that clerks will have several years to roll out the changes.

But clerks and voting rights advocates told Bolts that they are most concerned about those voters who do not closely follow news and information about elections, and who may be surprised to realize on Election Day in 2029 that they’ve not received a mail ballot.

“Regular people aren’t thinking about how to vote,” Menlove said. “They want to just show up on Election Day, or get their ballot in the mail, with a consistent system that they don’t have to think about.”

Critics are also worried about the requirement that voters report an ID number on their mail ballots. College students, members of Native American tribes, and unhoused people often struggle disproportionately to meet requirements for state-issued ID cards, and as a result are more often excluded from voting.

Native leaders in Utah were very vocal this legislative session in opposition to Burton’s bill, in large part because of its new ID rules. HB 300 would allow Native people to use a tribal ID card while voting, but they would have to photocopy that ID and enclose it with the mail ballot; voters who use a state-issued ID would not face that requirement.

Kseniya Kniazeva, director of Nomad Alliance, a nonprofit that supports unhoused Utahns, said the people she works with “constantly” have trouble obtaining and maintaining photo ID. HB 300’s requirement that any would-be mail voter must input the last four digits of an ID card, she told Bolts, could pose an insurmountable hurdle for some.

“People registering to vote is already a way of them saying, ‘I want to vote and I want a ballot,’” Kniazeva said. “Why would you want people to jump through more hoops?”

The Republican Party overwhelmingly controls Utah, easily winning statewide elections and boasting an ironclad supermajority in both chambers of the legislature. GOP lawmakers have played with election rules before, including by ignoring voter-approved redistricting reform to pass an aggressive gerrymander earlier this decade.

Still, Utah has occasionally seemed to be on a different wavelength than other red states, at least when it came to MAGA priorities. Many Republicans there voted for independent, conservative presidential candidate Evan McMullin in 2016—a clear rebuke of Trump, who again performed more poorly in Utah than did past GOP presidential nominees in 2020 and 2024, even as he decisively carried the state.

On the voting front, Utah has stood apart from most other red states in several ways beyond its universal vote-by-mail law: Utah offers same-day voter registration, unlike most states. It is one of vanishingly few Republican-controlled states remaining in the Electronic Registration Information Center, or ERIC, which is a coalition of states that share voter data in the interest of maintaining accurate voter rolls. Utah is also unusual among red states for restoring voting rights to people with felony convictions immediately upon release from prison.

Utah Senate Minority Leader Luz Escamilla, the top Democrat in the chamber, said these facts reflect a unique “Utah way”—but added that she thinks state politics are now drifting closer to the national GOP mean. She said that this legislature appears more willing to embrace the president’s lies about elections and to make new laws to resolve non-existent problems.

“It’s rough when you’re a superminority, but I always tell people I still have hope, and that the moment I become cynical and lose hope—that’s my cue to go,” Escamilla said. “It is getting harder now. It’s getting more painful. It is terrifying.”

Chapman echoed the sentiment, as she prepared to get to work to minimize bleeding of her voter rolls.

“Our community is better when more of us have a say in who’s representing us, not less,” she said. “This isn’t the way.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.