A New Plan to Lower Recidivism: Stimulus Payments to Formerly Incarcerated People

A bill filed in Colorado aims to break the cycle of incarceration by giving people up to $3,000 upon release from prison.

Alex Burness | January 12, 2024

A familiar problem awaits the Colorado legislature as it opens its annual 120-day lawmaking session this week: About half of the people released from its state prisons wind up reincarcerated within three years, a recidivism rate far outpacing that of almost any other state.

This has been true for years, even as Colorado devotes huge portions of its budget—about $1 billion last year—to its Department of Corrections. The state’s prison population boomed from the 1980s to the 2000s, dipped to modern-record lows as COVID-19 set in, and, today, Colorado has returned to incarcerating people at or above pre-pandemic rates.

James Coleman, a Democratic state senator whose Denver district includes the state’s largest women’s prison, says the legislature ought to try something new: giving more money to people exiting incarceration. He and three other Democrats are proposing Senate Bill 12 to allocate up to $3,000 per person upon release, for a one-year period. That would be a dramatic change to how Colorado currently treats people who exit its state prisons; most only receive a one-time debit card with $100, according to formerly incarcerated people and those who work with them.

This idea has been only lightly tested in the U.S., and only in the last few years. The New York-based nonprofit Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO), which is behind the Colorado effort, in 2020 began distributing checks of up to $2,750 to more than 10,000 people returning from incarceration in six states, including Colorado, plus a couple dozen cities. CEO says beneficiaries of that project, which it called the Returning Citizens Stimulus, were more likely to obtain and keep employment and housing, and to stay free from incarceration.

If passed, Coleman’s bill would make Colorado the first to codify a program of this sort in state law, according to CEO.

“The reality—$100 and a bus ticket—is not enough. People want the resources to not go back,” Coleman told Bolts on Wednesday. “We want to see people able to get out and utilize the dollars on housing, on workforce development, on opportunities to get jobs.”

This legislature hasn’t always been receptive to such bold changes within Colorado’s criminal legal system, especially lately, as the Democrats who control state government have largely moderated their stance after a brief embrace of reform around the 2020 protests for social and racial justice. But the bill piloting $3,000 cash assistance in the state starts from a promising position this year: Coleman’s co-sponsor in the Senate, Julie Gonzales of Denver, chairs the chamber’s powerful Judiciary Committee.

Passing SB 12 is just the first step. Coleman, Gonzales and others backing it will also have to convince state budget-writers to fund it. The bill proposes to open the stimulus program to anyone exiting a state prison, plus anyone exiting a county jail after being convicted of a felony offense. More than 7,000 people per year are released from Colorado prisons, but giving each of them $3,000 would cost more than $20 million, and history indicates this legislature is highly unlikely to fund an experiment of this sort to that extent. The scope of the proposal should become clearer in coming weeks.

“We’re still debating what a good sample group would be. How many people do we want to benefit?” Coleman said. “We want it to work first, and then we’ll see if we can get more funding in the future. What we know is it’s an innovative idea and no one’s done it.”

Several formerly incarcerated Coloradans told Bolts that the way the state currently releases people from prison sets them up for failure.

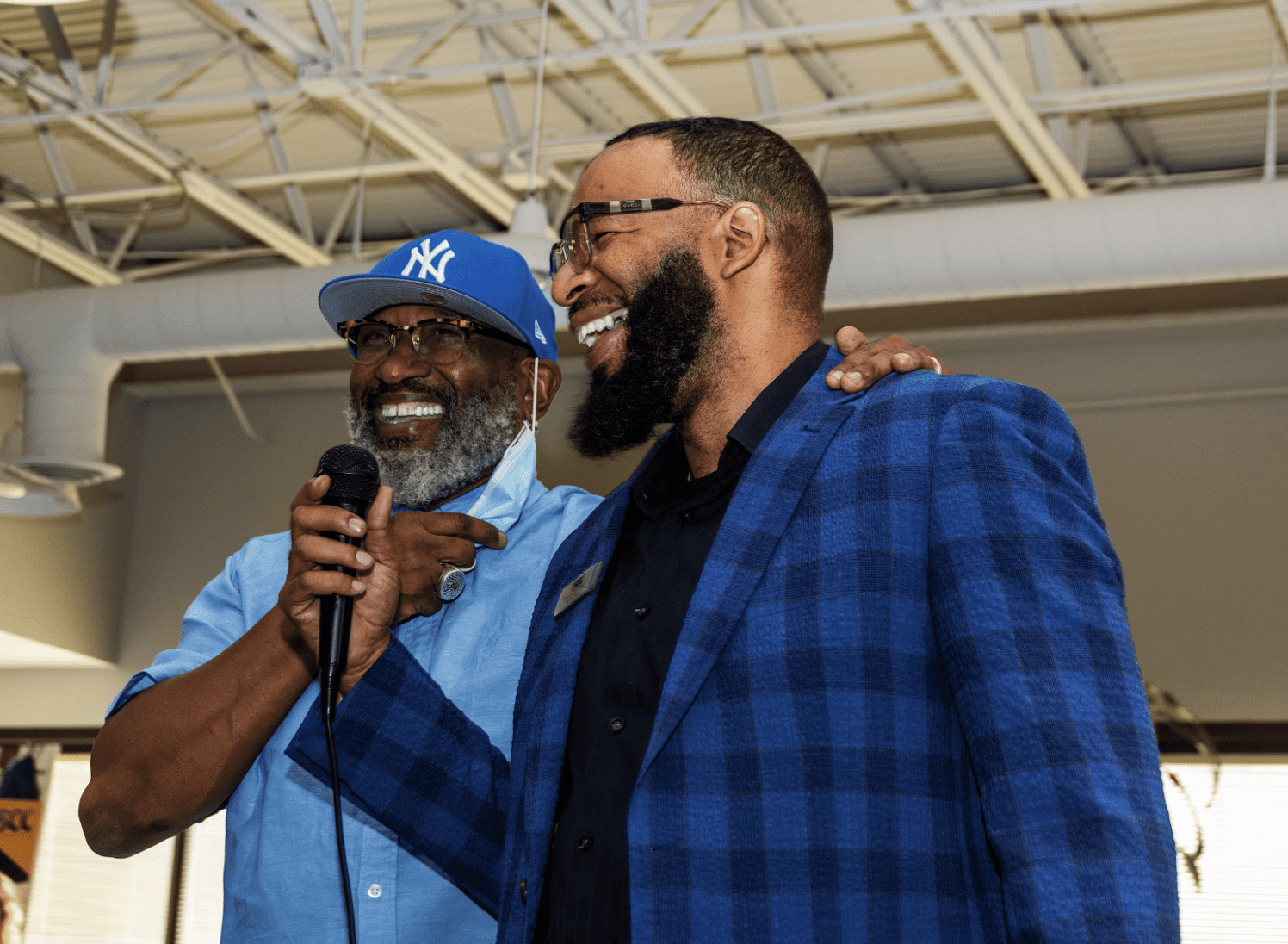

“The Department of Corrections says they don’t like to release people homeless, but they do that every day,” said Khalil Halim, who was once imprisoned in Colorado and is now executive director of Second Chance Center, a resource hub for people leaving incarceration. “There’s not a lot you can do with $100. People are liable to do whatever they need to to survive, so, with funds, even if it’s just staying in a hotel for a week or being able to buy food, it helps stabilize you to get wherever you need to get to.”

“You can stretch $3,000 for a few weeks,” he added. “You can’t stretch $100.”

In Jamiylah Nelson’s case, the $100 went quickly. “Personal hygiene products and underwear,” she told Bolts. “It’s not sustainable and it’s not helpful.” In 2021, Nelson was released after 14 years in prison, during which she struggled to build savings because, she says, the job she worked while incarcerated—training therapy dogs—paid her only about $4 per day.

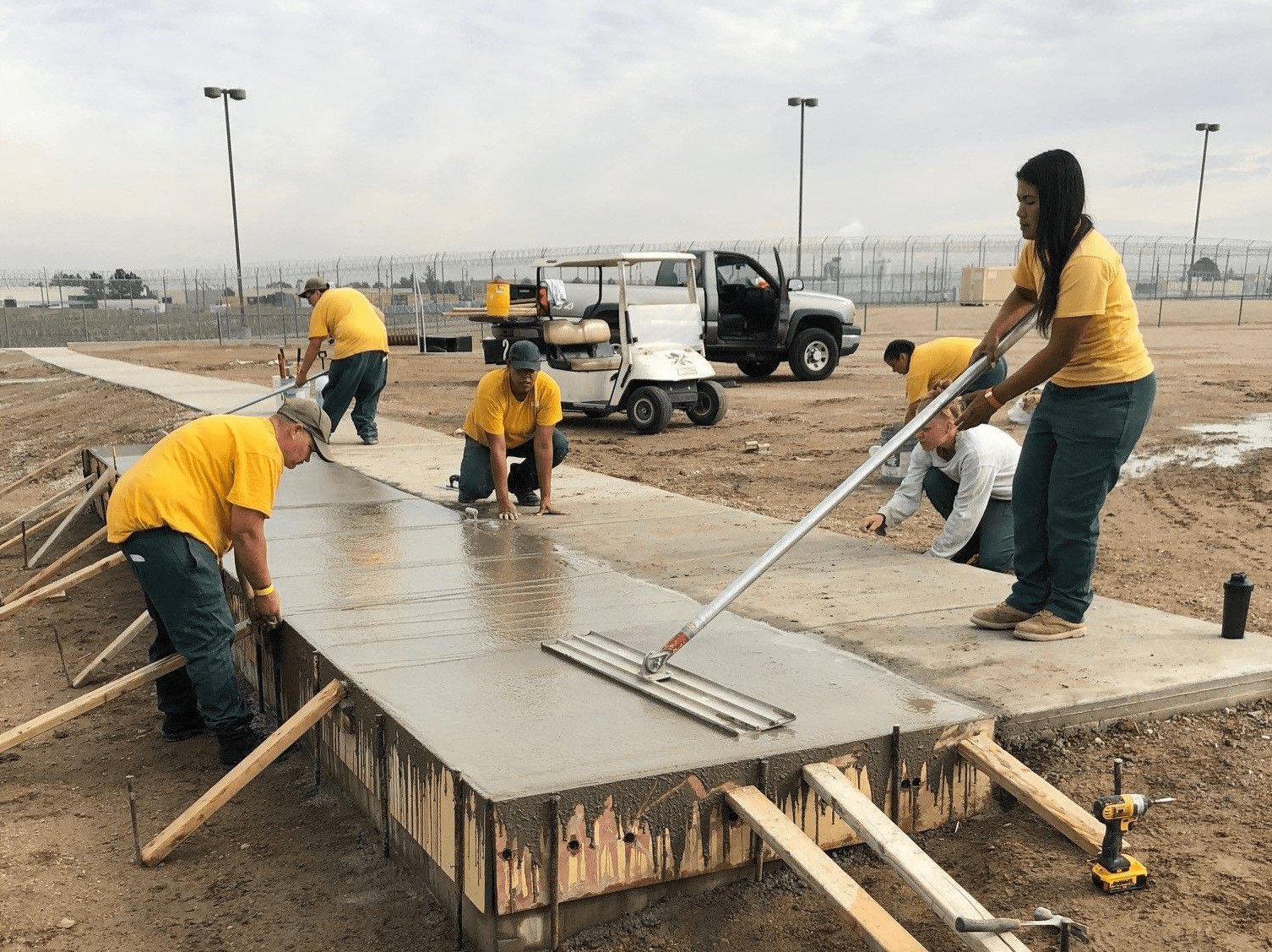

This is a typical story in Colorado and in prisons across the country, where incarcerated people are routinely forced into unpaid or radically underpaid work—even when performing highly skilled labor, like fighting wildfires. (Coloradans voted in 2018 to ban forced prisoner labor, but, as Bolts has previously reported, people in state prisons are still being punished for refusing work assignments.)

Nelson, who went to prison at 23, was in her late 30s by the time she was released, and felt out of touch with modern society. She had forgotten how to navigate the local public transportation system, which she says impeded her employment options after leaving prison. With an extra $3,000, she says, “I’d have been able to get me a car right away, and I’d have put some into savings. I didn’t have that opportunity, because everything was rolling so fast downhill as soon as I got out.” (Nelson has since stabilized and now works for the University of Denver.)

CEO’s survey of people involved in its Returning Citizens Stimulus experiment shows that beneficiaries mostly used the money on basic life expenses, like food, rent, transportation, and utilities.

SB 12 would follow a model similar to that program’s, by doling out checks in stages as opposed to all at once, and only if participants hit certain “milestone” achievements. In CEO’s 2020 pilot, the “milestone” markers included opening a bank account, building a budget, applying for Medicaid, participating in a job coaching session, and keeping appointments with probation or parole officers.

Colorado’s bill would order the Department of Corrections to issue a request for proposals by September from nonprofit groups interested in running the pilot. Whichever group is selected—probably CEO, a lobbyist for the bill told Bolts—would be responsible for setting the “milestone” markers.

Coleman said he’d like to see those tied to indicators of positive, prosocial progress. Valerie Greenhagen, who directs CEO’s work in the Rocky Mountain region, told Bolts the benchmarks should not place obstacles in front of the money. “We’re looking at what the individual we’re working with is struggling with,” she said. “The milestones themselves can be a fairly low lift and they really are designed to meet the person where they’re at.”

In its pilot, CEO distributed checks in three phases, and it reports that more than 80 percent of surveyed participants received all three payments.

Formerly incarcerated Coloradans interviewed for this story all say they’re comfortable with the “milestone” system written into Coleman’s proposal.

“Giving somebody a blank check is not exactly doing them a service,” said Paul Keener of Aurora, who was released in 2019 after eight years in prison. “I’m all for financial assistance, but for having it administered through a system that does community placement or community service for those people being released.”

Added Halim, “We know that if we can provide additional support, such as help with the rent, getting into classes, then our recidivism rate goes down. If you just give a person the money, there’s no stability added to that.”

But Simone Price, director of organizing for CEO, says she hopes Colorado and others will eventually start giving more money to people after incarceration without attaching so many requirements. The only recent state legislative effort to propose that so far was SB 1304 in California, which earmarked $1,300 payments to those exiting prison and which passed the legislature in 2022—but Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom declined to sign the bill into law.

With the concept of substantial cash assistance upon re-entry being so untested, Colorado’s bill proposes a pilot program running just one year. Coleman says he hopes to use that period to collect data and to build a case for long-term funding.

He thinks the results could be compelling. It currently costs nearly $47,000 on average per year to incarcerate someone in a Colorado prison, according to state reports, and so the program could theoretically pay for itself if it leads to any meaningful dip in recidivism.

“It’s hard, when you’re running a bill you’ve never had before, to justify a high dollar amount,” Coleman said. “So we either pay at the beginning, and potentially save $47,000 from a single person not being incarcerated, or we pay at the end.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.