Colorado Session Starts with Familiar Setback for Criminal Justice Reformers

A proposed pilot program to provide cash aid to formerly incarcerated people died quickly in the state Senate, which was already a graveyard for progressive ambitions last year.

| February 12, 2024

Colorado lawmakers wasted little time this year squashing an ambitious proposal that was meant to help people transition out of prison. Senate Bill 12, killed by a committee in the state Senate last week, early in the state’s legislative session, would have allocated up to $3,000 in conditional cash assistance for anyone exiting prison in the state.

SB 12 intended to help people reenter society and avoid the stumbles that lead many to be reincarcerated by providing them with seed money to cover basic expenses as they looked to find stable housing and employment on the outside. Colorado’s reincarceration rate is higher than that of almost any other state; half of the people released from its state prisons are sent back behind bars within three years.

The bill’s failure promptly signaled that Colorado’s 2024 session may replay last year’s dynamics on criminal justice issues; the state Senate became a graveyard for reform legislation despite Democrats’ 23-12 advantage in the chamber.

Some progressive lawmakers hoped to change that dynamic but at least one core obstacle carried over: the design of the Senate Judiciary Committee, the body that reviews virtually all criminal justice legislation. As Bolts reported in early 2023, Democratic leaders’ decision to appoint Senator Dylan Roberts, a career prosecutor and frequent opponent of criminal justice reforms, to the committee was bound to chokehold their ambitions, and did last year.

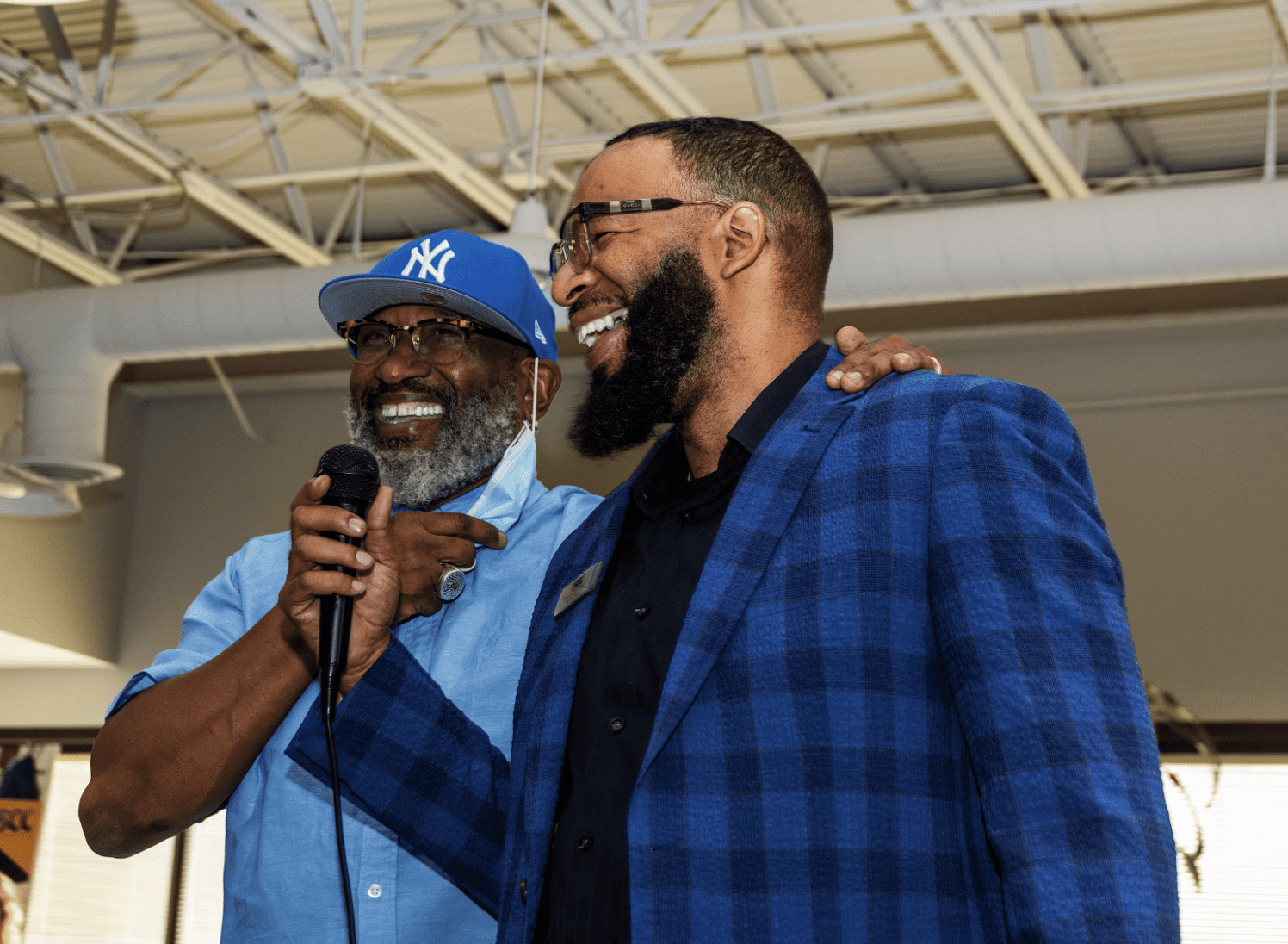

Roberts, whose vote can swing the five-person committee since he’s one of three Democrats, is the reason SB 12 failed last week, one of the bill’s chief sponsors told Bolts.

“We didn’t have the votes,” said Senator James Coleman, a Democrat from Denver, pointing to Roberts as the Democratic holdout. Roberts did not respond to an interview request following the bill’s tabling last week, but he told The Denver Post in January that he was concerned with how much SB 12 proposed to spend—up to $22.5 million by 2026—and that he felt the bill wasn’t written with sufficient oversight to ensure accountability to taxpayers. The state Department of Corrections had lobbied against the bill, too, on similar grounds.

Lacking the support to advance the bill out of committee, Coleman and his cosponsor Julie Gonzales, a Denver Democrat who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, made a motion on Wednesday to indefinitely delay consideration of the bill, the state’s equivalent to killing legislation for a session. Both vowed to retry it next year.

Gonzales told Bolts that the bill would have faced “stronger headwinds” than Roberts even if it had made it past the Judiciary Committee, which motivated her decision to agree to table it. The Appropriations Committee, where two centrist Democrats hold a lot of clout, loomed as the next obstacle. Pointing to the state’s “really tight budget situation,” Gonzales says that she wants to find ways to better justify the bill’s price tag.

Proponents of SB 12 say it could cut costs if it led to any meaningful decrease in recidivism and reincarceration, given the enormous cost of imprisoning someone—about $50,000 a year in Colorado. The state’s prison system spends roughly $1 billion a year, and fails to release many of its detainees in a condition to thrive; incarcerated people often face chronic homelessness and unemployment after their release.

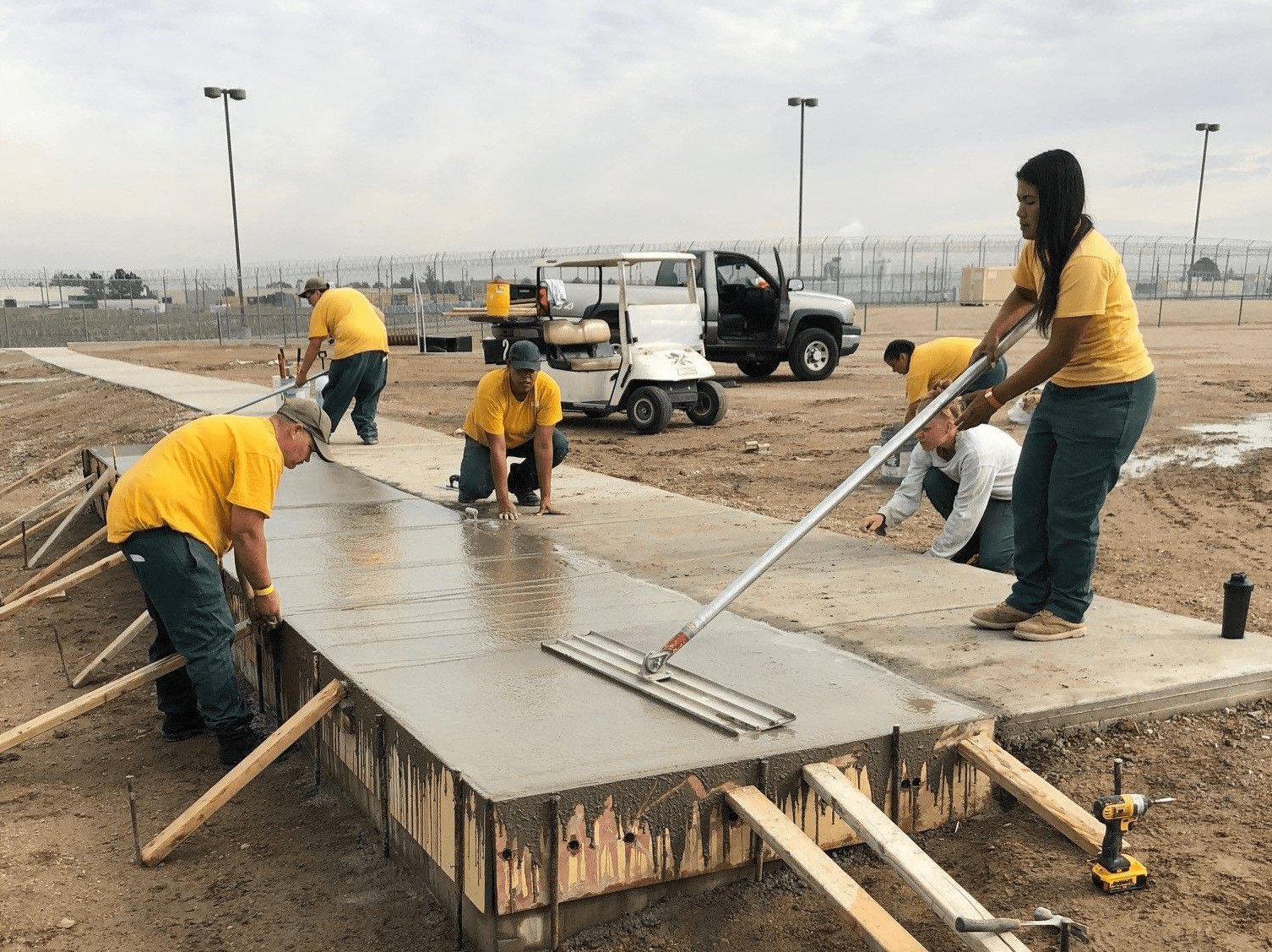

The state gives most people who are released a one-time debit of $100, a sum that formerly incarcerated Coloradoans say is vastly insufficient. The state also radically underpays people for labor they perform while they’re in prison, adding to their challenge to have resources for basic expenses when they’re released.

As she testified against SB 12 before the Senate Judiciary Committee last month, Adrienne Sanchez, the chief lobbyist for the state Department of Corrections, was asked by Gonzales how much the state pays its prison laborers. “Less than a dollar a day,” Sanchez responded.

Critics of the bill, including Sanchez, also took issue with the fact that SB 12 was clearly written with a single vendor in mind: the Center for Employment Opportunities, a New York-based nonprofit behind a 2020 national project to distribute checks of up to $2,750 to people leaving prison. They said this risked an anti-competitive process, to the possible detriment of other groups working in prison re-entry in Colorado.

Nowhere in the U.S. has a bill like SB 12 ever passed, and the Center for Employment Opportunities, which advocates for states and localities to adopt such stimulus payments, had hoped to plant a flag in Colorado this year.

Still, SB 12 was limited in scope: It called for a pilot program that would expire after a year. But Coleman says he finds it difficult in general to rally enthusiasm at the Capitol for policy that challenges the status quo, even for a one-year experiment.

“It’s a larger issue, where we aren’t all in alignment in the party,” Coleman said. “I wish this world was different. We’ll get there eventually.”

Those fault lines within the Democratic Party were on full display last year, when a slew of progressive legislation ended up derailing or getting significantly weakened. Among that group was a bill to raise the minimum age at which a child can be prosecuted, to shield preteens from prosecution. “It’s perplexing, particularly when you have a Democratic Party that runs on a platform of social justice,” Dafna Gozani, an attorney with the National Center for Youth Law who helped advocate for the bill, told Bolts at the time.

But Democrats last year also passed some reform bills, including a law to help protect children from being tricked by law enforcement in police interrogations, and another to curb local immigration detention. Those successes helped fuel cautious progressive ambition for 2024, though it’s not taken long for familiar political dynamics to reemerge this year.

Even before the session began, Democratic Governor Jared Polis vowed to veto any attempt to permit safe drug-use sites. This is a proposal many years in the making in Colorado, and one city leaders in Denver have previously embraced, but the plan now seems indefinitely sidelined.

Polis’sveto pen is an occasional character in Colorado’s criminal justice politics. He blocked a bill last year, for example, that was meant to make it a little easier for incarcerated people to request clemency from him. Most often, he signals opposition through backchannels or vague public statements of concern, and Democratic lawmakers kill legislation before it ever reaches his desk.

This year, Colorado lawmakers will also consider a slate of bills that would ramp up criminal penalties for certain lower-level offenses. Some legislation pending now would increase punishment for operating a commercial vehicle without proper licensure, for stealing guns, for harming police dogs, and for not complying with a police officer’s order to present an ID. The state adopted landmark legislation in 2021 to make the state’s misdemeanor laws less punishing, but critics have since argued that the changes made the state’s penal code too permissive.

Coleman regrets that his opponents on these issues are leaning toward just keeping people in prison, rather than proposing approaches to slow down the revolving door of incarceration. “What is the alternative, if it’s not reentry cash?” he asks.

Tristan Gorman, a lobbyist for the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar, thought SB 12 was an opportunity to show a different way. It “would have invested a modest amount of money in actual prevention,” she said. “Why wouldn’t we at least try that after the failure and suffering caused by decades of mass incarceration?”

Gorman added, “Generally, the state seems to have plenty of money to react to crime with punishment, no matter how much it costs taxpayers or how ineffective it is at preventing crime.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.