Direct Democracy Scores a Win in Michigan’s High Court. Can It Survive November?

The state supreme court overturned a GOP maneuver to bypass two citizen-led initiatives. The ruling was a party-line vote, and the court’s majority could flip this fall.

| August 5, 2024

Michigan progressives gathered enough signatures in 2018 to put two labor measures on the ballot: one to raise the minimum wage, another to mandate paid sick time for employees. Republican lawmakers, who ran the state at that time, thwarted the proposals with a brazen two-step maneuver. Before the measures were put before voters, they adopted legislation that enacted both into law exactly as organizers had drafted them; this eliminated them from the ballot. But once Election Day passed, lawmakers reconvened and gutted the laws they had just passed, all but erasing organizers’ work.

The Michigan Supreme Court struck back on Wednesday, finding that the legislature’s scheme to bypass the citizen initiatives was unconstitutional.

Michigan workers will soon reap major benefits from the ruling. In February, the minimum wage will increase by $2, and employers will be required to provide paid sick leave for all employees.

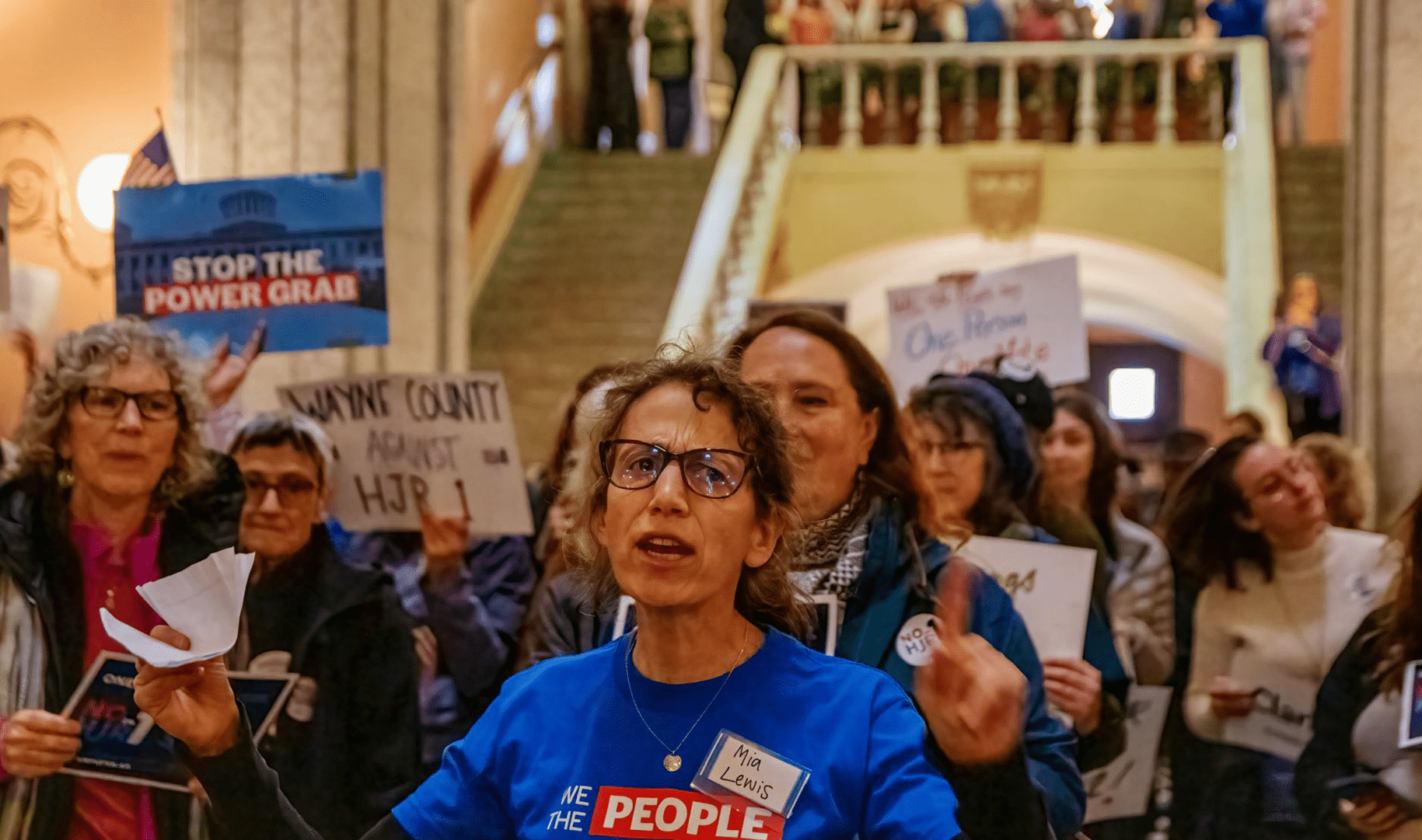

But the decision also provides a robust affirmation of direct democracy. The court’s Democratic majority stepped in to protect a process that has come under heavy assault in Michigan and elsewhere.

The legislature’s actions “violated the people’s constitutionally guaranteed right to propose and enact laws through the initiative process,” Justice Elizabeth Welch wrote for the majority.

This Michigan ruling came two weeks after the Utah supreme court created new safeguards for direct democracy. There, too, the ruling rebuffed Republicans who had gutted a suite of citizen initiatives; Utah lawmakers don’t have carte blanche to just override any ballot measure, the court ruled.

State courts historically have affirmed only narrow protections for ballot measures. But as GOP-run states have aggressively overturned initiatives, and made it harder to place them on the ballot in the first place, some jurists have turned to state constitutions and argued that they strongly protect access to democracy. Welch nodded to this argument in her Michigan decision, when she evoked “our Constitution’s commitment to ‘the democracy principle.’” Proposing laws is a “power that the people reserved to themselves,” she wrote; this power “must ‘be saved if possible’ from ‘evasion or parry by the legislature.’”

People watching from other states now hope that the back-to-back rulings in Michigan and Utah inspires other state courts to also push back on encroachments.

“Although state courts do not have to follow decisions from other states, they often look to such decisions for guidance,” Derek Clinger, an attorney at the State Democracy Research Initiative who contributed to an amicus brief that argued against Michigan lawmakers in this case, wrote in an analysis of the case. “[This opinion] may therefore persuade courts in other states to not allow technicalities or machinations to frustrate the people’s initiative and referendum powers.”

Within Michigan, though, the future of this new commitment to direct democracy is uncertain.

The supreme court split along party lines to issue this 4-3 decision. The four Democratic justices formed the majority and the three Republican justices dissented.

But the court could flip this November when two seats are up for grabs. Democratic Justice Kyra Harris Bolden, who was appointed last year by Governor Gretchen Whitmer, is running to stay on the court. Voters will also fill the seat of a retiring Republican, Justice David Viviano.

The GOP would capture control of the court if it sweeps both seats this fall. And while there’s no guarantee how new justices would rule on a similar case in the future, the divide last week signals that a GOP majority would severely threaten this precedent.

When North Carolina’s supreme court flipped to the GOP in 2022, conservatives flexed their newfound power to quickly reverse precedents and steer a new course on democracy and voting rights cases.

Michigan Republicans will choose their two supreme court candidates at a convention in late August, and at least five people are hoping to grab these spots. (While parties choose their nominees for November, these candidates’ party affiliation does not show up on the ballot.) One contender, Matt DePerno, is a prominent purveyor of false conspiracy theories about rampant voter fraud. DePerno, the party’s failed attorney general nominee in 2022, pursued a legal case to overturn the results of the 2020 election. He was charged last year for tampering with election equipment.

In recent years, major decisions by Michigan’s high court have often come down to a party-line split, raising the stakes of the November elections on issues beyond election law. In 2022, the court two years ago issued a string of 4-3 decisions that created new protections for youth from severe punishments. Just last week, the court found that the state cannot put people on the sexual offender registry for crimes that are nonsexual; that decision came in a 5-2 vote, with Justice Elizabeth Clement, a moderate Republican, joining her four Democratic colleagues.

The court has issued other recent decisions safeguarding ballot initiatives. Two years ago, Republicans on the State Board of Canvassers abruptly blocked two proposed constitutional amendments from making the ballot, flouting the recommendations of the Bureau of Elections that had determined that the measures had enough signatures. The court reinstated the amendments in a pair of 5-2 rulings that, again, saw Clement join four Democrats.

Clement stuck with the party in last week’s ruling, however. She wrote in a dissent that she did not think that the legislature’s actions were unconstitutional.

“There is certainly reason to be frustrated by the Legislature’s actions here: enacting laws proposed by initiative petition to avoid ballot approval only to substantially alter them in the same legislative session,” she wrote. “But nothing in Article 2, § 9 restricts the Legislature from doing so. And as tempting as it might be to step into the breach, this Court lacks the power to create restrictions out of whole cloth.”

This section of the Michigan constitution was drafted in 1913, and since then Michiganders have enjoyed the power to propose statutes of their own creation. Once organizers gather enough signatures to place a proposal on the ballot, the legislature has two basic options. It can either adopt the proposal as is, which means it becomes law without needing to go on the ballot. Or it can reject the statute; at that point, the measure goes to voters who can force its adoption.

If voters adopt a measure, the legislature can’t get rid of it easily, as three fourths of lawmakers must agree to modify it. Republicans in 2018, who were very far from having such a supermajority, would have been boxed in if they’d let the minimum wage and sick leave measures go to voters. Instead, they chose a maneuver known as “adopt and amend;” they “adopted” the measures in September 2018, preventing citizens from voting on them, and then they “amended” their own laws on simple majority votes in December 2018.

The legislature insisted it was following the law. It relied on a last-minute advisory opinion from Republican Attorney General Bill Schuette, who overturned a 1964 opinion by Democratic Attorney General Frank Kelley that such a maneuver was unconstitutional.

Clement agreed with Schuette on Wednesday. If the legislature chooses to adopt a proposal, she wrote in her dissent, it can use its normal lawmaking power after that point to modify it as it pleases.

Welch’s majority opinion was thoroughly unconvinced.

“It is difficult to fathom that the framers intended for voters to expend countless resources and time to gather thousands of signatures to place an initiative on the ballot only to have to do so all over again via a referendum after the Legislature adopts and then amends the initiative,” she wrote.

Welch added, “Allowing the Legislature to bypass the voters and repeal the very same law it just passed in the same legislative session thwarts the voters’ ability to participate in the lawmaking process.”

The court’s decision comes with a major caveat. It only bars lawmakers from amending a measure within the same session in which they’ve adopted it. But they can still do it in a future session; the court took specific issue with “the lame duck legislators” who, in December 2018, “avoided the democratic accountability” that the constitution “was designed to provide.”

This keeps the door wide open to lawmakers adopting a proposed measure to keep it off the ballot one year—and then gutting it in the following calendar year.

Still, it can get more difficult to repeal a law as time passes because people are more likely to be feeling its effects. The minimum wage measure that was poised to be on the 2018 ballot would have raised people’s wages starting on Jan. 1, 2019. Republicans rolled it back in December before the increase went into effect. Having to wait until early 2019 would have meant cutting people’s actual wages—a maneuver that would have been far less palatable politically.

Plus, the Democratic justices on Wednesday signaled that they’ll stay vigilant in the future—if they can keep their majority in November, that is.

Welch in her opinion snapped at lawmakers’ attempt to thwart their constituents, writing, “The people bestow power unto the branches of government, not the other way around.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.