Elections Mailbag: Your Questions on Next Week’s Races, Answered

Why can’t New Yorkers rank the candidates? What are school boards to watch? Is sewer socialism back? We’ve got answers about the 2025 elections.

| October 27, 2025

Earlier this month, we encouraged you to share any questions you have about November’s elections. I had just written a guide featuring more than 180 critical contests all around the country, and I wanted to hear what was on our readers’ minds.

Today, I tackle six of your questions, from the stakes of next week’s races for immigration policy and school boards to the rules of voting in New York City.

Navigate to the question that most interests you, or simply scroll down to explore them all:

What are local candidates proposing when it comes to ICE?

Why isn’t New York City using ranked-choice voting in November as well?

Which school board elections are you watching?

What states are electing supreme court judges?

Are we seeing a resurgence of municipal socialism?

What do these elections mean for the midterms?

This is the latest in our “Ask Bolts” series where we answer our readers—elections mailbag edition.

Want updates on these races?

Sign up for our newsletter.

Are there people running who are pushing back on ICE? What does that look like? —Sam, from Virginia

Let’s start with sheriffs, who have vast discretion on how to assist ICE. They can help the agency and detain immigrants on its behalf, or they can pull back from such partnerships. Since Trump’s return to power, many sheriffs have rushed to expand ICE’s reach and capacity, and Bolts’ Alex Burness wrote in June that there’s been a stark lack of candidates running for sheriff on a platform of scaling back collaboration. For instance, Chesapeake, Virginia, and Erie County (Buffalo), New York, two populous places that voted against Trump last year, each have sheriffs that are helping ICE; but no Democrat filed to run against either of them.

One exception this fall: Pennsylvania’s Bucks County, a swing county in the Philly suburbs.

In fact, Bucks is the only county with a contested sheriff’s race this year that’s part of ICE’s 287(g) program, which empowers sheriff’s deputies to act like federal immigration agents. Republican Sheriff Fred Harran signed the contract earlier this year, and his Democratic challenger Danny Ceisler has said he’d quickly terminate it if he enters office.

At the mayoral level, these debates are also splitting elections like Albuquerque’s where candidates differ on how local police departments should respond to ICE. Meanwhile, progressive jurisdictions are facing residents’ pressure to get more creative about flexing local powers like prosecution and zoning, though Bolts has repeatedly reported on how even officials who’ve vowed to stand up to ICE are entangled with the agency.

Another major question is how New Jersey and Virginia’s state elections will affect those states’ policies toward ICE. Currently, local police and sheriffs in New Jersey are banned by the state from entering into various forms of agreement with ICE but Republican Jack Ciattarelli has vowed to scrap those protections if he gets into the governor’s mansion. In Virginia, Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin signed an executive order this year to get local law enforcement to assist ICE; Democratic nominee Abigail Spanberger has said she’ll rescind it if she wins.

Why isn’t New York using ranked choice voting to decide the mayor’s race [in the general election]? —Gabe, from New York

Ranked-choice voting was the talk of the town in New York this spring: Democrats were using it to decide their nominee in the mayoral race, and candidates were forming alliances to urge voters to rank one another.

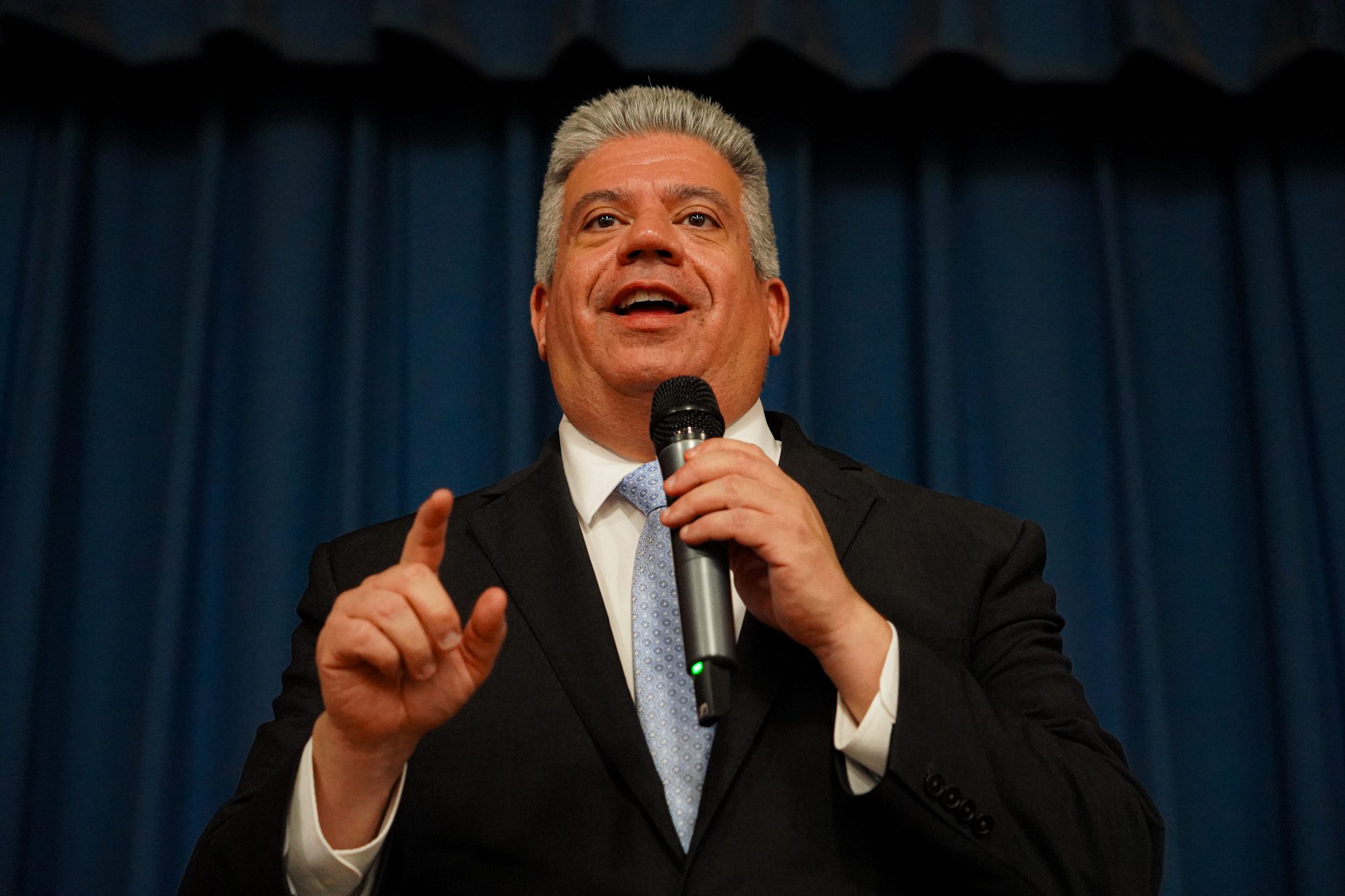

But the rules of the general election are a lot more conventional: Voters get to choose just one candidate, and whoever has the most votes wins. In fact, opponents of Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani have bemoaned that the field is too split for anyone to beat him, and President Trump reportedly helped coax Mayor Eric Adams out of the race.

I asked why the general election is designed differently than the primary to Susan Lerner, the president of Common Cause New York, who was a leading advocate behind the 2019 ballot measure that brought ranked-choice to the city.

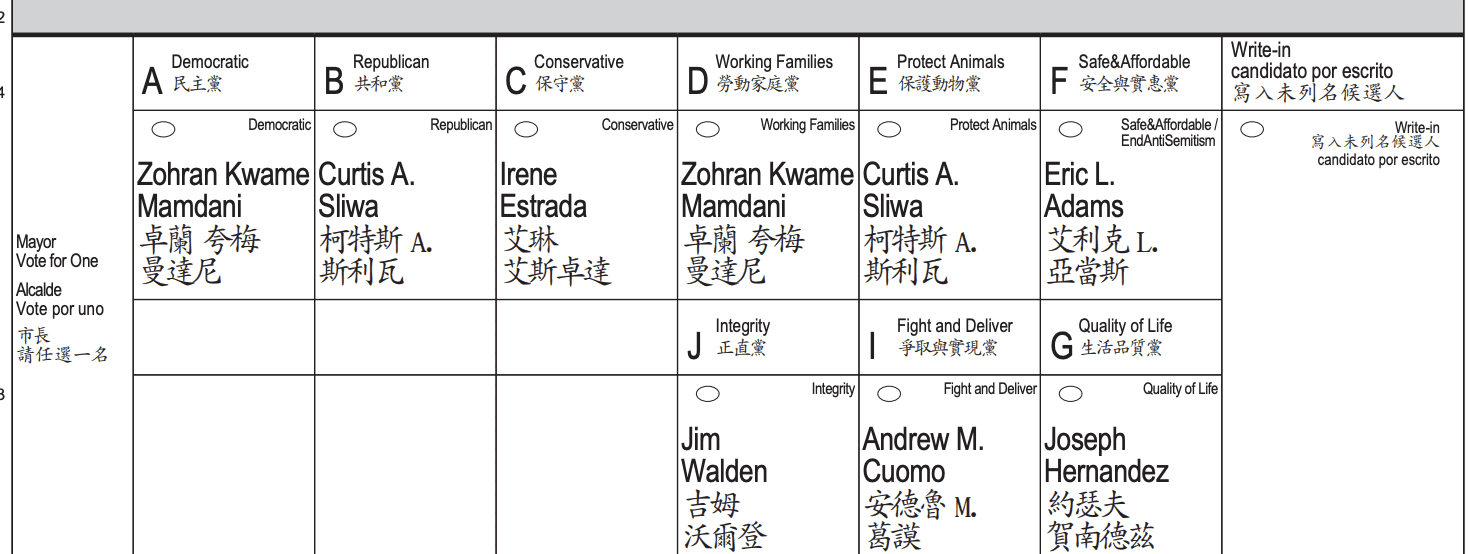

Lerner said the major reason why advocates proposed that ranked-choice only apply to primaries was a fear that, otherwise, it’d interfere with a feature of New York’s general elections known as fusion voting.

New York State recognizes several third parties (such as the Conservative Party and the Working Families Party), each of which is guaranteed a line on general election ballots. In an unusual arrangement, if a candidate is endorsed by different parties, their name is listed on the ballot several times; the votes they receive on each row are then added up to form one total.

Mamdani, for instance, will appear twice on November’s mayoral ballot, shown below: once as the Democratic nominee, and once as the Working Families Party nominee.

Lerner told Bolts that she and other advocates were worried that it’d be too complicated to ask voters to rank the general election ballot—since some candidates’ names would show up multiple times.

“We were concerned that, in the general, where a candidate’s name could appear two or three times on the ballot, it’d be confusing to the voter in the general election as they shouldn’t rank the same candidate more than once,” she said. “In setting up a ranked-choice voting system, we knew that it’s necessary to have very effective and vigorous communication.”

But Lerner says she’d be open to revising the rules now that the initial work of introducing and explaining ranked-choice voting is completed: “It’s clearly part of the political context of the city, voters are comfortable with it, now is time to see if it should be expanded to the general.”

Are there any big school board elections that will determine partisan control? Also, are there any sites that track the partisan composition/political leanings of important school boards? —Ollie

There’s no centralized method to track who are the nation’s tens of thousands of school board members, let alone what their politics may be. Plus, school board races are often ostensibly nonpartisan, so determining whether an ideological bloc enjoys a majority may require tracking down candidate rhetoric on social media, or parsing the endorsements of groups like Moms for Liberty, the right-wing organization behind the recent conservative gains on school boards.

Local newsrooms like The York Dispatch have done yeoman’s work to track the politics of these boards, as have interested citizens like Frank Strong, an educator opposed to conservative takeovers who regularly updates a guide that deciphers school board races in North Texas.

In my guide to November’s elections, I’ve identified several school boards where the board’s ideological majority is at stake next week—and where there’s been considerable debate in recent years over the rights of LGBTQ+ students and over book bans.

In one of Colorado’s largest school districts, for instance, a right-wing majority has sided with anti-LGBTQ+ politicians and undermined a state health survey but it could lose its 4-3 edge this fall. Conservatives could also lose their majority on the school board of Cypress-Fairbanks, one of the largest school districts in Texas, in the Houston region; this board has been dominated by the Christian right in recent years, as The Texas Monthly reported earlier this year.

Finally, Pennsylvania’s Bucks County became a poster child for right-wing takeovers across several local school boards in 2021, though conservatives there already lost their majorities two years ago. This year, Democrats are hoping to go further by seizing all seats on the once-GOP Pennridge and Central Bucks boards.

In Pennsylvania we are retaining judges, and I’ve seen video ads that stress the stakes. I wonder how many places this sort of thing is up for a vote? —Joe, from Pennsylvania

Indeed, Pennsylvanians are deciding whether to keep three of their supreme court justices, as well as two appellate court judges, in elections where the only options are simply “yes” or “no;” that’s known as a retention election. Don’t miss Bolts’ reporting on these races.

Pennsylvania is the only state electing state judges this fall. But judicial races are common nationwide and they’ll be a major storyline in 2026, just like they were in 2022 and 2024.

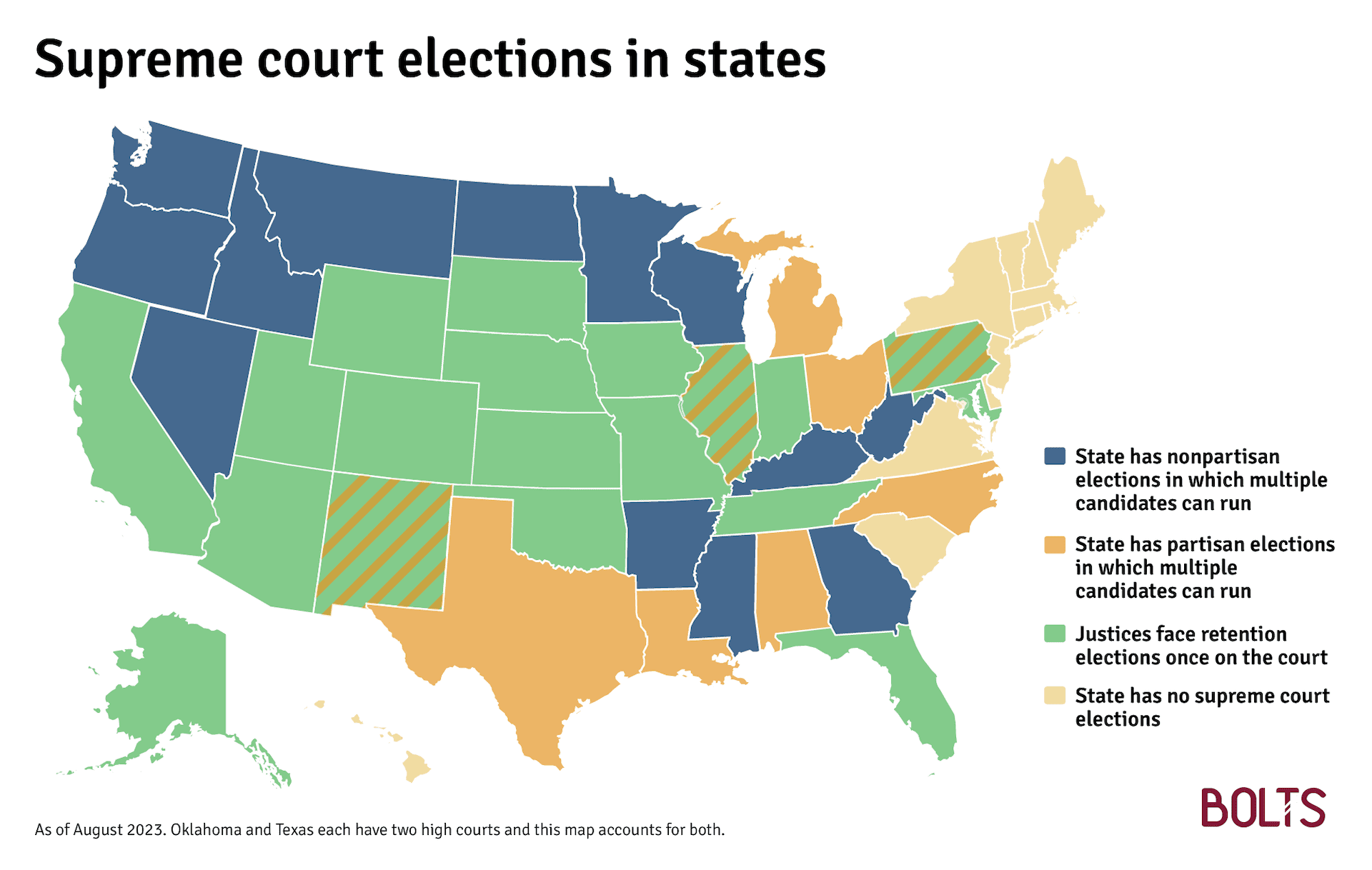

As Bolts has unpacked in this guide, 31 states hold some type of election for their justices.

Nineteen states organize retention elections, like those currently on the ballot in Pennsylvania.

Retention elections are rarely competitive. In fact, there are many states like Arizona, Florida and Indiana in which no justice has ever lost retention: It simply tends to be difficult to mobilize voters to oust officials who have little name recognition when no one is running against them. Still, there are signs that retention races may be growing more salient; Oklahoma conservatives, for instance, succeeded in ousting a justice for the first time last year in a bid to push the court to the right.

Pennsylvania’s system is unusual in one key respect, though. It’s one of only three states, alongside Illinois and New Mexico, with a hybrid system where justices first run in a partisan race where they may face an opponent, and then run for retention in subsequent cycles.

But historically, that hasn’t made a clear difference on how competitive retention elections get. With the exceptions of one Pennsylvania justice who wasn’t retained in 2005, and one Illinois justice who wasn’t retained in 2020, justices in these states routinely coast by overwhelming margins. And as Alex Burness reported in Bolts last month, Pennsylvania Republicans seem to be struggling to land on a coherent message to galvanize voters to break the mold.

Several mayor’s races, like in New York City, Seattle, and Boston, suggest the rise of the left at the municipal level but with a strong focus on good service provision. Is this a resurgence of the Sewer Socialism of the 20th century? —Becky

Many commentators have drawn parallels in recent years between the democratic socialists running for city offices today and the municipal socialism that took root in Milwaukee from 1910 to 1960 and came to be known as “sewer socialism” for its focus on delivering public services.

Zohran Mamdani has embraced that legacy himself: In an interview with The Nation in August, the New York mayoral candidate said the lessons he takes from Milwaukee’s socialist history is the importance of “improving the services and social goods that working people experience each and every day: the sewers, the clean drinking water, the parks.”

I shared this question with Joshua Kluever, a historian of twentieth-century American politics who has written on sewer socialism, to see what he makes of this parallel. He said he sees “many similarities” between the campaigns of Mamdani and [Seattle candidate Katie] Wilson and Milwaukee’s sewer socialists.

But he added that it’s useful to recall how that label was actually used to grasp what’s specific about that tradition. “The sewer socialist label was a derogatory label—an insult or tease—used by more radical, left-wing socialists/communists towards the more moderate Milwaukee socialists. To radicals like Daniel De Leon and leftists within the IWW, the social democrats of Milwaukee weren’t pushing hard enough to alleviate the working class and bring about social revolution; all they could do was improve the sewer systems or improve drinking water.”

For Kluever, what distinguished Milwaukee’s leaders was how they stood firm that, from a socialist perspective, “those are important things for a government to provide… Sewer socialists did more than just fix the sewers in Milwaukee. They built public parks, made the streetcar system safer, expanded the city’s port, and ensured safer working and living conditions for Milwaukee residents.” Kluever anticipates that, as mayor, Mamdani will face criticism from his left that he isn’t going “far enough” but, Kluever says, “his programs of capping the rent and free buses are radical and part of the long socialist tradition of good service provision.”

My goal is to have a better sense of the current political climate as far as federal election implications are concerned. How should I generally approach these upcoming state and local elections? What caution should I take when interpreting or extrapolating these results? —Gene

The election most directly relevant to future federal races is whether Californians adopt Prop 50; that will affect roughly five congressional seats in 2026. Beyond that, it’s risky to draw strong inferences about the future. There are only four states filling statewide offices this fall, and turnout is likely to be lower across the board than it will be in the midterms.

Nathaniel Rakich, an elections analyst who has repeatedly written on this question, told me he, too, is generally wary of extrapolating from off-year results. “This is especially true for the big-ticket governors’ races; gubernatorial races in general tend to be more idiosyncratic and candidate-driven than any other type of election,” he said. But he added that special elections for legislative and congressional seats have some predictive power, though only when they’re considered in the aggregate.

The elections website The Downballot maintains a special elections tracker to calculate such an aggregate. And its editor David Nir tells me he’ll be watching November’s legislative races. “So far this year, Democratic candidates have performed an average of 15 points better than you’d expect,” he said. “That’s strong—and even stronger than in the 2017-18 cycle, when Democrats took back the House. There will be almost three dozen more specials around the country on Nov. 4, so we’ll soon have a lot more data to tell us where this trend is headed.”

Rakich also says that “the results of some scattered local elections could be clues as to whether certain parts of the country are undergoing a political realignment (or reversing one).” He cites the major gains the GOP made in 2021 in Nassau County, on Long Island, that foreshadowed the area’s rightward shift in 2022 and 2024. Democrats’ bids to claw back power in Nassau County next month is testing how permanent the GOP’s gains are.

A similar example: Republicans in 2023 flipped a city council district in the Bronx, winning their first seat in that borough since 1983; that foreshadowed the borough’s massive shift of 22.5 percentage points toward Trump in the 2024 presidential race. Now, Democrats are looking to gain that seat back. Other regions to watch include the New Jersey municipalities with large Latino populations that have also shifted Republican since 2021, and Northern Virginia, which has suffered the brunt of the DOGE cuts to the federal workforce.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.