In Criminal Justice Elections This Year, ICE Contracts Are on the Hot Seat

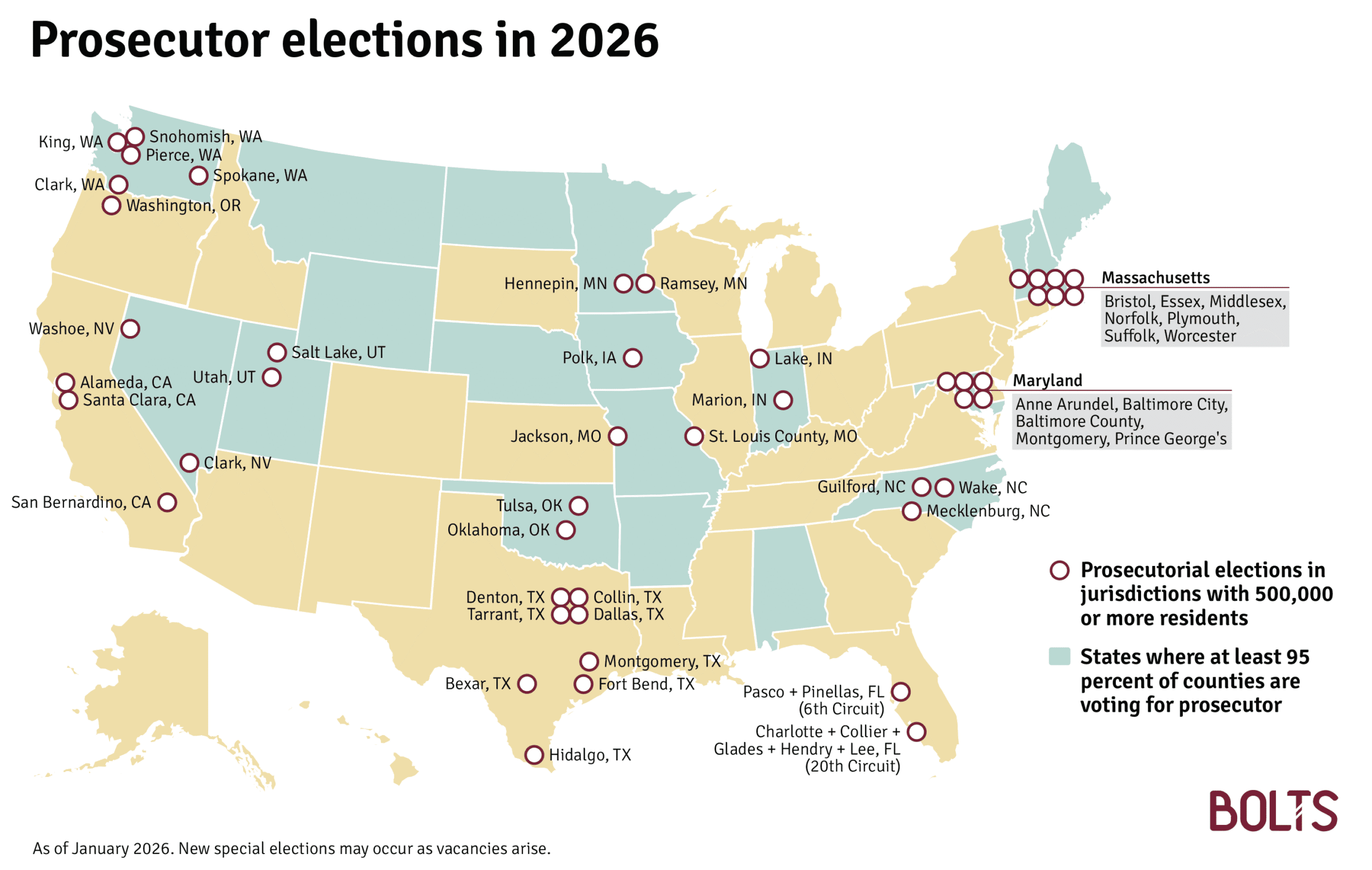

With roughly 2,400 elections for prosecutor and sheriff in 2026, Bolts reviews the map and early hotspots that will shape criminal punishment and law enforcement practices.

| January 26, 2026

Do you have a question about how local and state governments can, and are, responding to ICE? Let us know this week, and we will do our best to answer.

An hour north of D.C., a Maryland county that opposed Donald Trump in the 2024 presidential election is closely assisting his immigration crackdown.

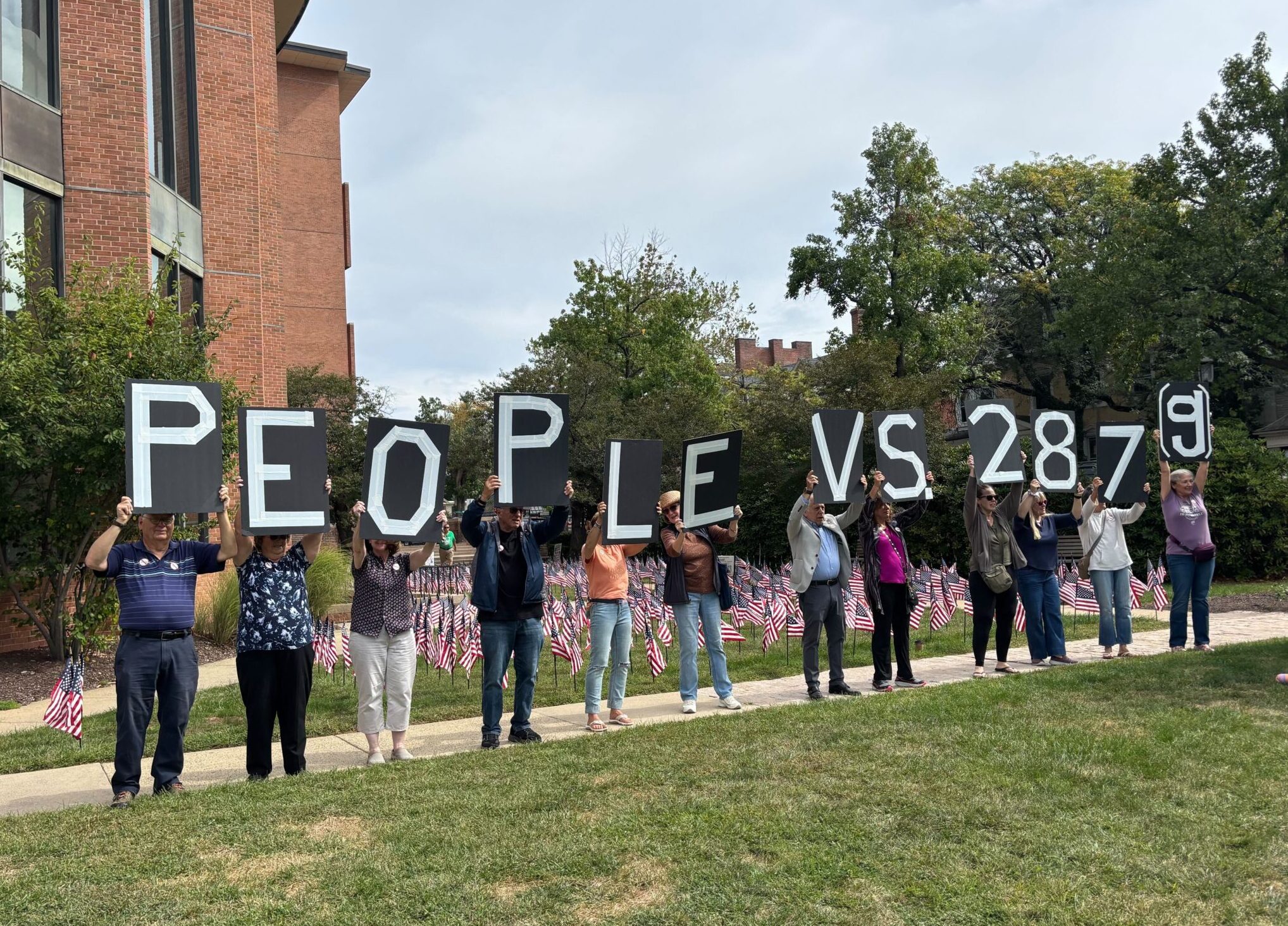

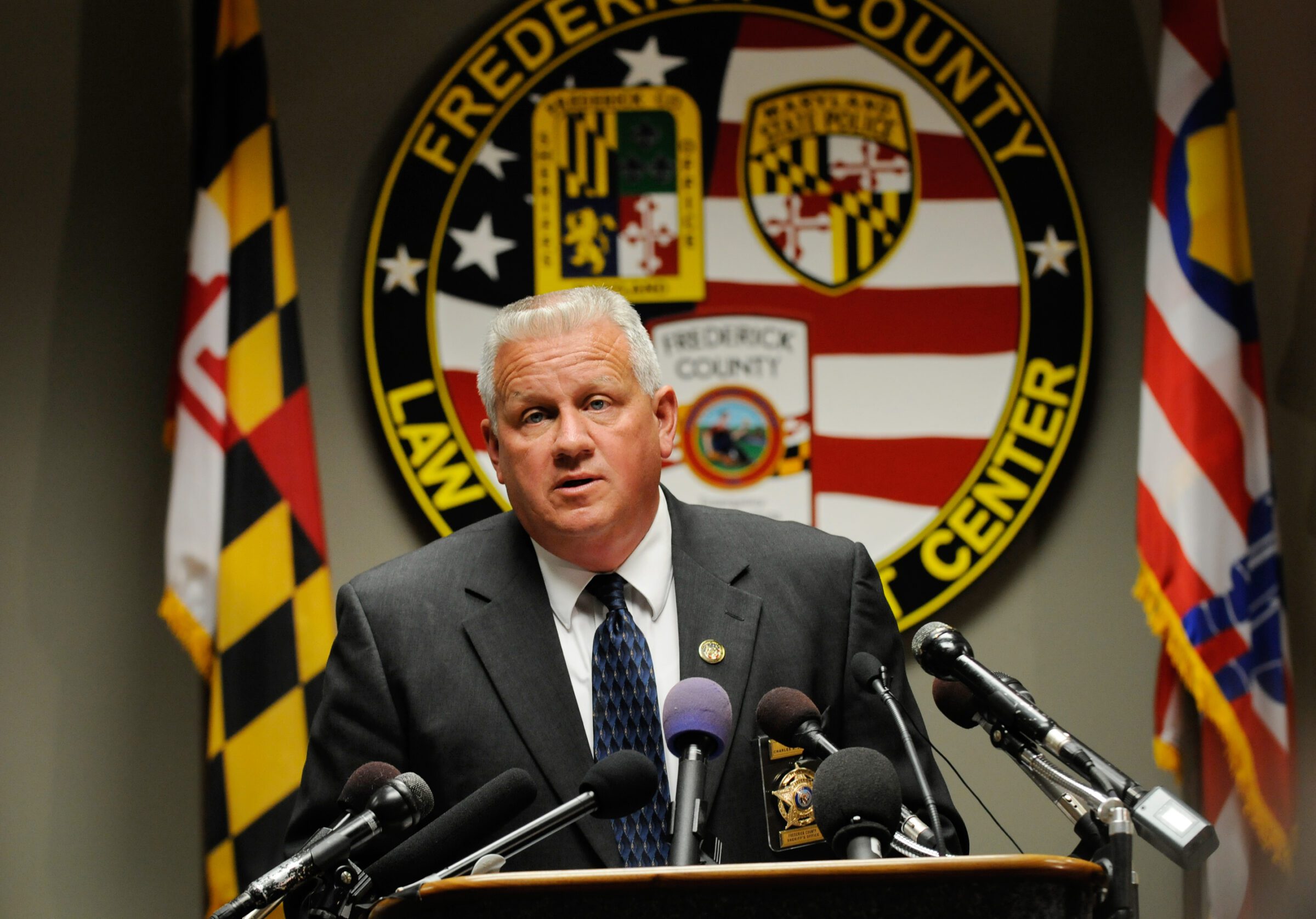

Frederick County Sheriff Chuck Jenkins, an immigration hardliner tied to national far-right groups, has long targeted local immigrant communities, partnering with ICE and joining its 287(g) program, which authorizes local deputies to act like federal agents.

But a new sheriff would have the authority to terminate the department’s relationship with ICE. Jenkins, a Republican who has long been entrenched in Frederick County, is up for reelection this year as communities across the country debate local police collaboration with Trump’s crackdown on immigrants. Jenkins survived a tight race four years ago, but challengers have prevailed elsewhere under similar circumstances. Just this fall, a GOP sheriff in Pennsylvania was ousted by a Democrat who ran on quitting the 287(g) program.

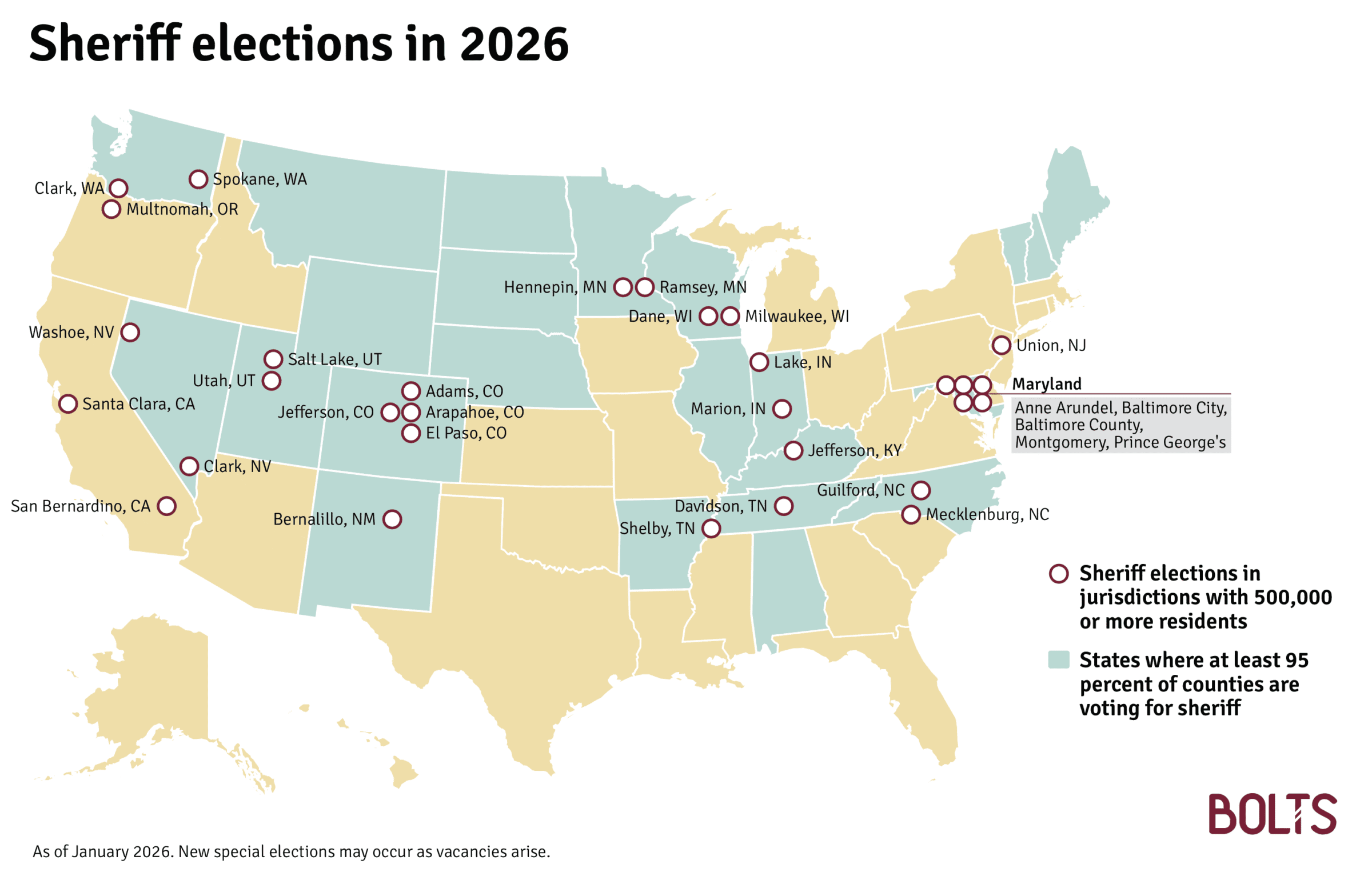

There are over 2,400 races for prosecutor and sheriff like this one all around the nation in 2026; they could hand voters plenty of opportunities to reshape local policies on policing, punishment, and immigration enforcement.

These elected officials have vast discretion over sentencing, incarceration, and how or whether to help ICE. They’re also responsible for the dangerous conditions that are typical in many local jails, and for the frequent failures to hold law enforcement officers accountable for misconduct.

Kicking off Bolts’ coverage of these contests today is our annual overview of the counties that are holding these elections for prosecutor and for sheriff: Find our full list here.

Which Counties Elect Their Prosecutors and Sheriffs in 2026?

The field is already set in some contests where the filing deadline has passed. The prosecutor races in Durham and Fort Worth, for instance, are each set for a rematch of 2022 elections shaped by disagreements over criminal justice reform. In other states, deadlines are still months away and elections are still undefined. But even at this stage, key hotspots are emerging.

There’s the wide-open race to replace Minneapolis’ retiring prosecutor, at a time when local officials are clashing with federal governments over investigating the ICE agents who killed Renee Good and Alex Pretti. A reform prosecutor wants a new term in Burlington, while incumbents who beat progressives four years ago are again up for reelection in Boston, Las Vegas, and Baltimore County.

Sheriff elections, meanwhile, will test voters’ appetite for collaborating with Trump’s deportation agenda. At this juncture, the reelection bids of pro-ICE sheriffs in blue or swing counties of Maryland, New Hampshire, New York, Montana, and Wisconsin stand out. We’ll also monitor whether jail and policing practices are debated in the campaigns to lead embattled departments such as in Springfield, Illinois.

And while this guide is largely focused on sheriffs and prosecutors, you’ll find some bonus local races. In the DMV region, for instance, an agreement with ICE may hinge on the contest for Baltimore County executive, while in Washington, D.C., approaches to policing are shaping up as a defining issue of the upcoming mayoral election.

Read more for an early preview of some of the stakes of the 2026 criminal justice elections.

Subscribe to our newsletter

for more coverage of these local elections

1. The sheriff races where immigration enforcement is on the line

Since Trump’s return to power, sheriffs have rushed to partner with a supercharged ICE, exploiting the myriad ways local law enforcement can help federal authorities identify and detain undocumented immigrants.

The 287(g) program is the highest-profile program with which sheriffs assist ICE. Until 2025, it only enabled sheriff’s deputies to act like federal agents within county jails; Trump expanded it, reviving an older model abolished under President Obama that lets deputies arrest people for immigration violations during their day-to-day duties, such as regular patrols or while stopping cars on highways.

Most counties in the program are conservative areas with GOP sheriffs, terrain that may be tricky for a candidate running to protect immigrants’ rights. Still, Bucks County, the Pennsylvania county that ousted its pro-ICE sheriff last November, had narrowly backed the president the year before.

This year, another swing state may see a parallel dynamic. Wisconsin is electing all of its sheriffs and, similarly to Bucks, several competitive counties are run by Republican sheriffs who have joined the program. These include Kenosha, Sauk, and Winnebago.

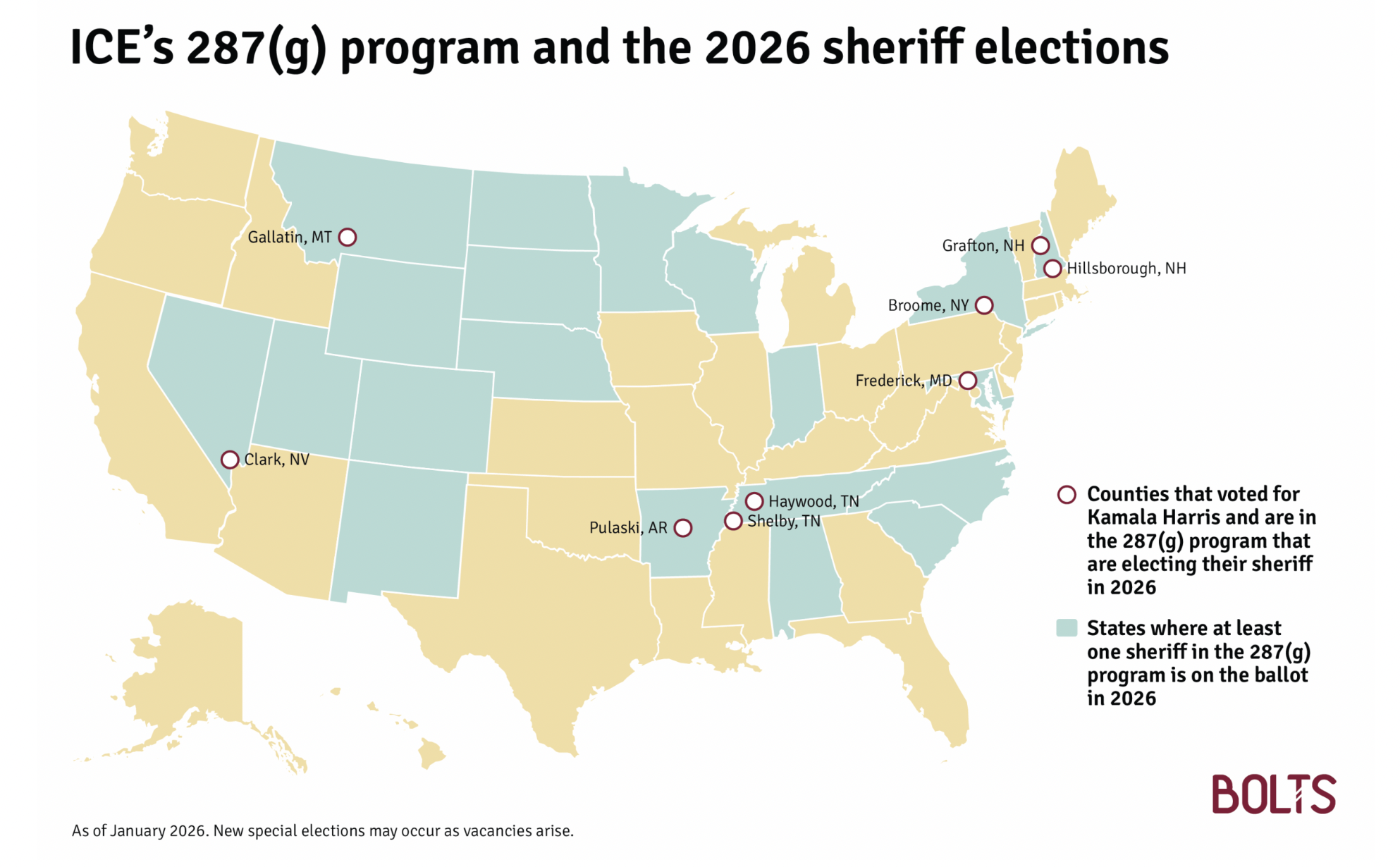

But the 287(g) counties most likely to change course on immigration are those that already rejected Trump in 2024, opting for Kamala Harris instead.

There aren’t many of those nationwide, but a Bolts analysis found nine such counties with sheriff races this year.

In one of these, Arkansas’ Pulaski County (Little Rock), state Republicans have passed a law requiring that sheriffs join the 287(g) program. But in the other seven, sheriffs still have authority to quit the program. That includes Maryland’s Frederick County, as well as Montana’s Gallatin County (Bozeman), New Hampshire’s Grafton and Hillsborough counties, New York’s Broome County, and Tennessee’s Haywood and Shelby (Memphis) counties.

For immigrants’ rights advocates, the first challenge is recruitment; a county’s blue lean is no guarantee that there’ll be any candidate looking to curtail ties with ICE.

Bolts has frequently reported on pro-ICE sheriffs who run in territory hostile to Trump but face no challenger, or run with only nominal opposition. Last year, when pro-ICE candidates ran without opposition in her region of Virginia, one advocate told Bolts, “It drives me crazy… that there is a door with an opportunity and no one is taking advantage of it.”

Besides 287(g), sheriffs use many other programs to partner with federal authorities, such as Stonegarden grants that fund border operations. Under yet another program called SCAAP, sheriff offices receive money in exchange for providing DHS with information about detainees they have held in their jails; some sheriffs have recently quit SCAAP, but the financial incentive has drawn counties that otherwise tout their pro-immigrant policies, Bolts has found.

For instance, Minnesota’s Twin Cities have split on this policy. The sheriff’s office in Hennepin County (Minneapolis) did not receive funding from SCAAP for fiscal year 2024 but the sheriff’s office in Ramsey County (St. Paul) did. In 2026, both counties will elect their sheriff.

2. The sheriffs who oversee embattled departments

Besides their role on immigration, most sheriffs oversee vast departments with the authority to police and manage local jails. Many sheriffs’ tenures are rife with abuse but rarely draw political attention. Even when a sheriff faces an opponent, campaigns rarely center on the epidemic of jail deaths or on misconduct incidents.

Still, an election can at least force some public scrutiny. Many of the sheriff’s offices on the ballot this year have been hit with lawsuits recently over gruesome conditions in their jails or over violent acts committed by sheriff’s deputies—and over their failure to develop policies to stop these abuses.

This includes sheriffs in Wisconsin’s Milwaukee and Waukesha counties, Maryland’s Harford County, Minnesota’s Hennepin and Crow Wing counties, Colorado’s Huerfano County, and Illinois’ Morgan County. (You can view the full list of counties with sheriff races here.)

For instance, when a Sangamon County sheriff’s deputy in 2024 killed Sonya Massey near Springfield, Illinois’ state capital, it sparked nationwide protests; locally, a citizen commission met over a year and just released some reform recommendations. Voters now have to decide who’ll be their next sheriff, which is to say who would be the official to actually implement and oversee local reforms. The new GOP incumbent appointed in the wake of those protests faces a primary challenger in March who is running with an endorsement from the sheriff’s deputies union.

3. Clashes over criminal justice reform will continue in prosecutor races

Mary Moriarty’s triumph in Minneapolis’ last prosecutor race was a major win for criminal justice reformers, and the career public defender followed through with new policies meant to deemphasize punishment and combat racial discrimination. But she chose to retire this year rather than seek a second term, and the wide-open race to replace her is one of the clearest tests this cycle on whether voters will double down on endorsing a reform agenda.

Minnesota is not the only such hotspot as several other public officials associated with the progressive prosecutor movement are up for reelection this year. The prosecutor of Burlington, Vermont, who survived police union attacks four years ago has already said she is seeking a new term this year. In Durham, North Carolina, the reform–minded DA Satana Deberry faces a contested Democratic primary against local attorney Jonathan Wilson, whom she beat in 2022; Wilson has supported some of her policies like not prosecuting simple drug possession but also faulted her for being too lenient in some cases.

Inversely, fierce opponents of criminal justice reform who survived major challenges in 2022 will also be on the ballot.

They include Baltimore County State’s Attorney Scott Shellenberger, who faces multiple challengers four years after he narrowly survived over a progressive attorney in 2022; Las Vegas DA Steve Wolfson, who is known for his predilection for the death penalty and who last defeated an opponent who vowed to stop death sentences; and Plymouth County DA Tim Cruz, a Massachusetts Republican who beat a civil rights attorney in 2022.

And the list goes on—over 1,000 prosecutors are set to be elected in 2026, after all.

The field is already set in populous Tarrant County (Fort Worth), Texas, where Republican DA Phil Sorrells faces a rematch against Democrat Tiffany Burks; four years ago, Burks steered clear of promising systemic reforms but made promises like never prosecuting an abortion. In Dallas, DA John Creuzot faces a Democratic primary against Amber Givens, an embattled former judge who faced state sanctions before stepping down from the bench to run for DA. In North Carolina’s Buncombe County (Asheville), several defense attorneys are running on a progressive message for an open DA race that will be settled in the March primary.

Bolts is also watching contests for major offices in Boston, King County (Seattle), and St. Louis County where the field is still developing and deadlines are months away.

4. When the election is over before it starts

Four years ago, the DA of Mecklenburg County (Charlotte) prevailed against a challenger who assailed him for seeking excessive sentences and ballooning prisons. This year, Spencer Merriweather is sure to have an easier time: North Carolina’s filing deadline passed in December and no one filed to run against him in either the primary or the general election.

So while it’s only January, Merriweather is already virtually guaranteed to secure a new term this year once the election is officially decided in November.

That’s no surprise: Many prosecutor and sheriff races draw just one candidate, as Bolts has extensively reported over the years. They’re over before they start, and voters have no opportunity to debate these local policies.

The pattern is already stark in states where filing deadlines have passed. In North Carolina, 28 of this year’s 39 prosecutor elections drew a single candidate, and in Arkansas it’s 20 of the 28 prosecutor races—that’s 48 people who are already certain to waltz into office.

And this isn’t just a phenomenon in sparsely populated counties. No major-party candidate is running against Chicago’s sheriff, even though longtime incumbent Tom Dart has faced blowback and lawsuits over the many deaths in his jail. Other elections that will be uncontested include DA races in Texas’ Collier, Denton, and Montgomery counties, which are each home to over one million residents.

5. The other elections that may define criminal justice

2025 was defined by big-city mayoral contests that saw candidates clash on policing practices, immigration, accountability for officer misconduct, and homelessness.

In 2026, mayoral politics around law enforcement won’t be as big a dynamic. Only four cities of at least 500,000 are electing their chief executive—Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Oklahoma City, and Louisville—compared to nine last year.

In seeking a second term in Los Angeles, Karen Bass faces a slew of challengers, from Rae Huang, a democratic socialist activist, to Austin Beutner, a centrist former school superintendent, though neither have centered their bids on policing for now. That’s already a more potent issue in D.C, where Mayor Muriel Bowser is retiring. Progressive candidate Janeese Lewis George has opposed some of the mayor’s priorities on crime, such as when she was the only city council member to vote against a 2023 ordinance that made the city code more punitive; she faces Kenyan McDuffie, who recently resigned from city council and is more of a Browser ally.

In Louisville, Mayor Craig Greenberg faces a rematch with Shameka Parrish Wright, who was active in local Black Lives Matter protests as leader of the Louisville Bail Project. Amid smaller cities, watch Newark, where Mayor Ras Baraka has clashed with state officials over his efforts to strengthen police oversight; he was also detained by federal authorities when he tried to visit an immigration detention center.

Many other local elections will determine involvement with ICE. Baltimore County, for instance, agreed in 2025 to share information with federal immigration agents; the race for county executive this year will shape the future of that arrangement.

State elections, finally, could heavily influence policies on criminal justice and immigration.

There’ll be ballot measures that directly affect these issues, such as a constitutional amendment in Virginia to enable people to vote once they are released from prison, or a conservative initiative in Colorado to compel local police to assist ICE.

Voters will also decide who controls nearly all states, with 12 already emerging as early battlegrounds, and elect dozens of state supreme court justices. Democratic judges who have sided with criminal defendants in major recent decisions, like Michigan Justice Megan Cavanagh and North Carolina Justice Anita Earls, are up for reelection.

But even statewide races can fizzle out as uncontested elections. Take Nevada, where the deadline for judicial candidates passed earlier this month and no one filed to challenge the two conservative supreme court justices who are up for reelection this year. They’ll each get to run for a new six-year term unopposed.

Correction: The article has been updated to reflect that Santa Clara and San Bernardino counties have regular elections this year, even as other California counties moved their DA and sheriff races to 2028.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.