Twelve Questions Shaping Democracy and Voting Rights in 2024

Opportunities abound for states to ease ballot access and voter registration this year. But the specter of major showdowns over the results of the November elections also looms.

Michael Barajas, Alex Burness, Daniel Nichanian, Camille Squires | January 4, 2024

The upcoming presidential election is routinely cast as a battle over the future of democracy, but as we enter 2024, so much remains in flux about what democracy looks like this year.

After court rulings in December struck down several states’ electoral maps, from Michigan to New York, what districts will millions of people even vote in later this year? How prepared will local election offices be after suffering harassment for years? Will the Voting Rights Act (VRA) still stand as a tool for civil rights litigation in the wake of an ominous ruling that came in late 2023? Who will even be running elections in North Carolina and Wisconsin, two swing states that are experiencing an intense power struggle?

Our team at Bolts has identified a dozen key questions that will shape voting rights and democracy this year. This is born less of a desire to be comprehensive than to offer a preliminary roadmap for our own coverage.

That’s because, while some questions that matter to 2024 will come down to federal decisions—likely starting with decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court on Donald Trump’s prosecutions and presence on the ballot, and on the VRA’s fate—a lot will hinge on the policies and politics of state and local governments: your county clerk in charge of organizing Election Day, your county board that decides where to put ballot drop boxes, your lawmakers tweaking the rules of ballot initiatives, your secretary of state wielding the power to certify results. (Be sure to explore our state-by-state resources on who runs our elections and who counts our elections.)

These are the officials we will be tracking throughout the year to help us clarify the local landscape of voting rights and access to democracy during a critical election year.

1. How will federal courts affect voting rights and the 2024 election?

A maelstrom of major legal cases on voting rights and the 2024 election are currently working their way through the legal system, and many are heading straight toward the nation’s highest court.

The stakes are clear in: The U.S. Supreme Court

SCOTUS is set to hear several cases that will affect one presidential candidate: Donald Trump. The first is whether Trump will be allowed to appear on the ballot in several states. Colorado’s state supreme court disqualified him from the primary ballot in late December, ruling he was ineligible due to the Fourteenth Amendment because he engaged in an insurrection on January 6. (Maine’s secretary of state came to a similar conclusion one week later.) Trump has appealed the Colorado decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, though the justices have not yet announced whether and when they will hear the cases; their ruling is likely to also shape how other states do, amid the former president’s protests that his removal would unduly disenfranchise millions. The Supreme Court could also decide at least five other cases that touch Trump, including the shape of his Atlanta trial on charges that he tried to subvert the 2020 election in Georgia.

Also keep an eye on: SCOTUS may decide any major litigation that emerges in the aftermath of the November elections. But it’s also set to consider plenty of non-Trump voting rights cases this year, including several that may further gut the VRA. One devastating blow for the landmark civil rights law may come from a case out of Arkansas, where a federal appeals court ruled that private groups and individuals cannot bring VRA challenges. If the Supreme Court upholds this ruling, legal experts say it would make the law largely unenforceable. As the VRA continues to be weakened, some states have adopted state-level voting rights acts to reinforce its principles; debate may resume in Michigan and New Jersey this year over such legislation.

Federal appeals courts have also recently rejected other VRA claims, including in a case in which civil rights groups in Georgia challenged the state’s election system for its public utility commission as racially discriminatory. If the high court upholds the ruling, it would have major implications for the statewide elected utility commission in neighboring Alabama as well.

2. How will state election maps change by November?

Nearly four years after the decennial census that kicks off redistricting, election maps across the country remain in flux, and major legal and political battles are set to unfold this year. At stake is not just who will have power in each state, but also whether people get to vote under fair maps.

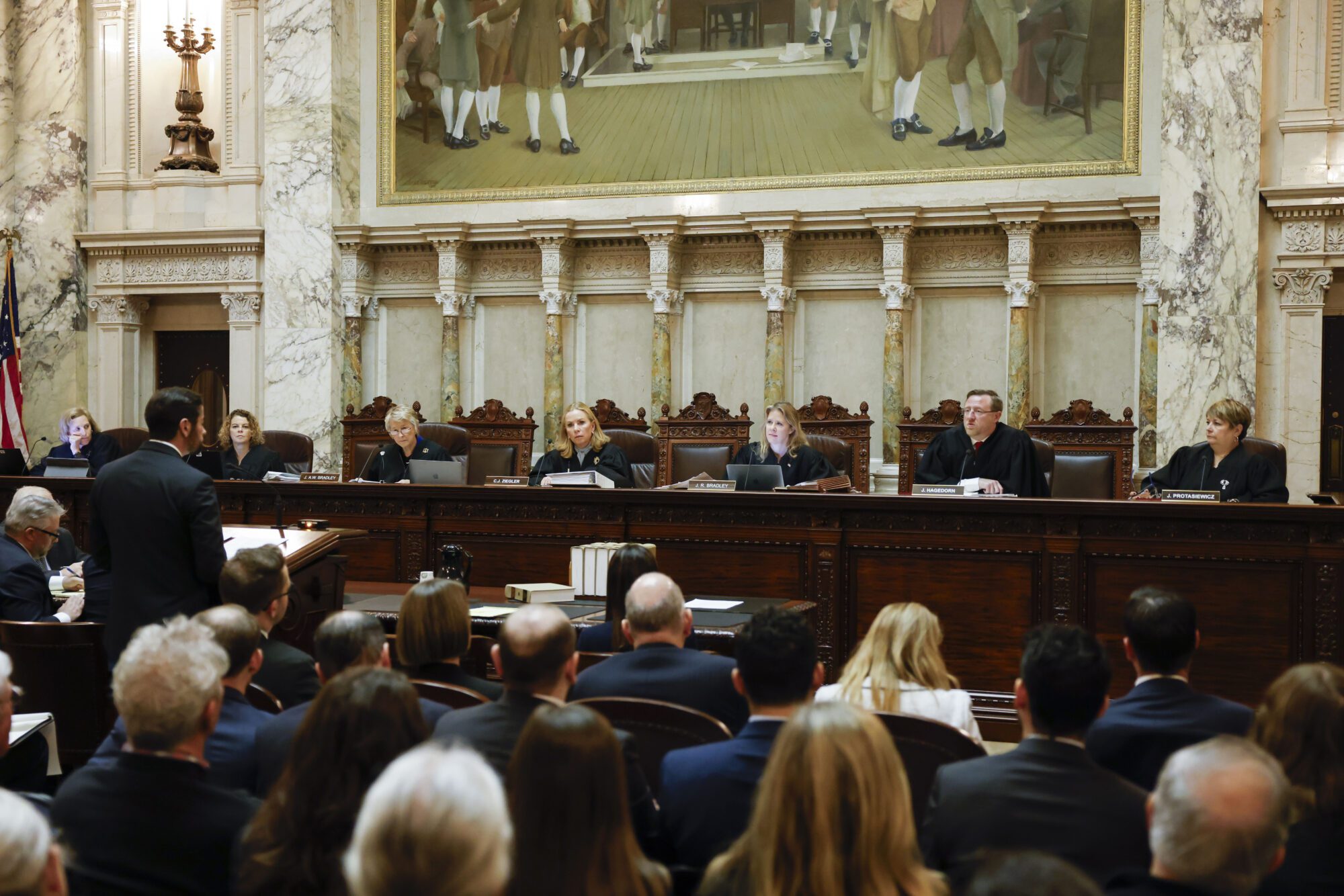

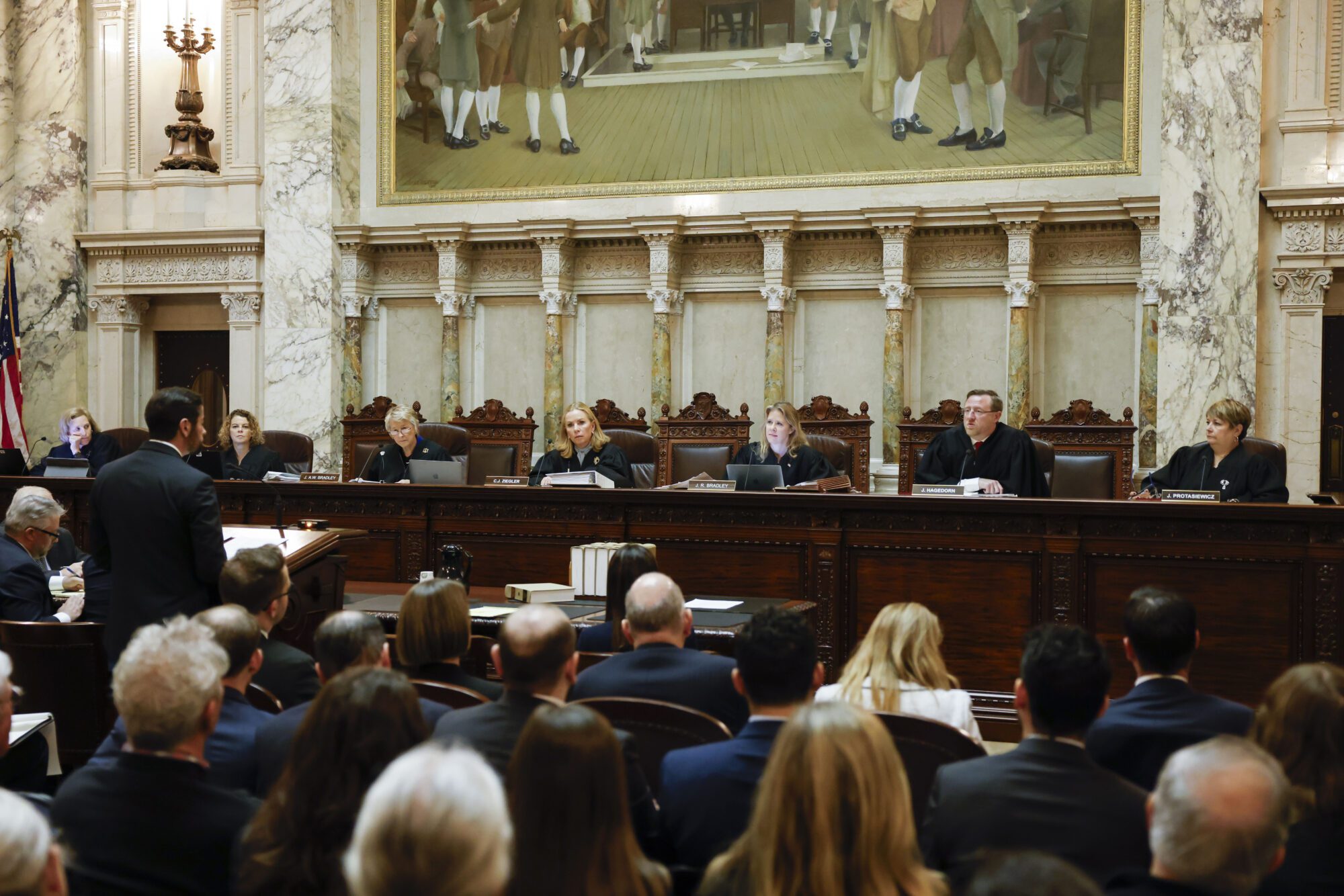

The stakes are clear in: Wisconsin

Wisconsin Republicans enjoy large legislative majorities that are effectively election-proof thanks to their gerrymandered maps, but 2023 began to unravel their hold on power. Liberals flipped the state’s supreme court in April after a heated campaign during which Janet Protasiewicz, the winning candidate, called the legislative maps “rigged.” And in late December, the court issued a 4-3 ruling, with liberals in the majority, striking down the legislative maps.

But there’s still a long way to go before voters can get fairer maps in November. The court set up a process to draw new remedial maps, but left the door open for lawmakers to try first. The state’s GOP speaker has largely backed off his earlier threats to impeach Protasiewicz but still has not ruled it out. And Democratic groups must decide whether they’ll also sue over the congressional map and whether to do so in state court.

Also keep an eye on: A federal judge ordered Louisiana to draw a new congressional map by late January to stop diluting the power of Black voters, but lawmakers may stall. Michigan needs to redraw its legislative maps after another federal ruling found that 13 districts violated the Voting Rights Act. New York is also in the midst of a fresh round of congressional redistricting after Democrats won a court battle in December, though it remains to be seen whether the process ends up producing minor tweaks or an aggressive Democratic gerrymander. And from Texas to Florida, there’s still active litigation in many states alleging that maps are unlawful.

3. How well will local election officials and offices be prepared to handle the election?

The country’s elections workforce has been decimated in the past few years, amid a deluge of threats and harassment stemming from coordinated efforts by some Republicans to attack and undermine local and state administrators, as well as funding challenges. The capacity of these local offices will now be seriously tested in 2024.

The stakes are clear in: Nevada

Nevada has suffered acutely since 2020 from election-worker brain-drain. Not a week into 2024, these woes have already deepened: Jamie Rodriguez, the elections chief in Washoe County (Reno), the second most populous county in the state, announced her resignation on Tuesday. Rodriguez’s predecessor, Deanna Spikula, herself stepped down in 2022 after some residents smeared her as a “traitor” and threatened her office. In an interview with Bolts last year, Cisco Aguilar, Nevada’s Democratic secretary of state, warned of where he sees this all heading: “If we don’t take care of the human component,” he said, “these elections are going to be nowhere near where we want them to be or expect them to be, and that’s only going to deteriorate the credibility of elections overall.”

Also keep an eye on: Election officials have similarly resigned en masse in recent years in many states, from Colorado to Pennsylvania, leading many to worry about the amount of experience lost. And while election workers are crucial, so is election infrastructure. Aging voting equipment presents a projected multi-billion-dollar problem. Look to Louisiana, for example, to see why this is worth worrying about: That state’s voting machines are nearly 20 years old. They break down often and, when they do, elections administrators struggle to obtain the parts to fix them. One local elections chief told Bolts her office is “barely hanging on”— a statement many of her counterparts around the country have echoed.

4. Who will actually run the 2024 elections?

It’s tough enough for election offices to prepare for the 2024 cycle amid all the personal overhaul they’ve experienced since 2024. But in some of the nation’s most important battleground states, election rules and administrators are in limbo going into this critical year.

The stakes are clear in: Wisconsin

Wisconsin Election Commission administrator Meagan Wolfe became a target for right-wing conspiracists in the wake of the 2020 election, and GOP lawmakers resolved to oust her last year. After a complicated set of maneuvers, Senate Republicans voted to remove her from the position in September, but a judge later ruled that vote had no legal effect for now. Wolfe has not stepped down from her position even though her term has technically expired. This political and legal imbroglio has created huge uncertainty over who will actually administer Wisconsin’s elections this year. Adding to the limbo: Wisconsinites in April will elect some of the local officials who will then run the state’s August and November elections.

Also keep an eye on: North Carolina Republicans were primed to oust the director of the state’s State Elections Board, Karen Brinson Bell, thanks to a new law they passed last year. The law changed the structure of the board so that it no longer has a Democratic majority, instead creating an even split between parties, and it entrusted the GOP legislature with resolving ties; this would likely set up Republicans to oust Bell and usher in new leadership. But a state court in late November blocked the law in a preliminary ruling, a legal dispute set to resolve this year.

5. What happens if any election officials try to stall or halt certification?

After losing the 2020 presidential race, Donald Trump asked state and local officials to stall or stop the election’s certification, hoping to overturn state results and convince his congressional allies to accept his slates of fake electors. If Trump loses the presidential race again this fall and repeats that strategy, would he find allies who are willing to disrupt the process and have the authority to stop it? Be sure to bookmark our nationwide resource on who counts elections since answering this difficult question requires a keen understanding of the mechanisms of power in every state, which Bolts will track throughout 2024.

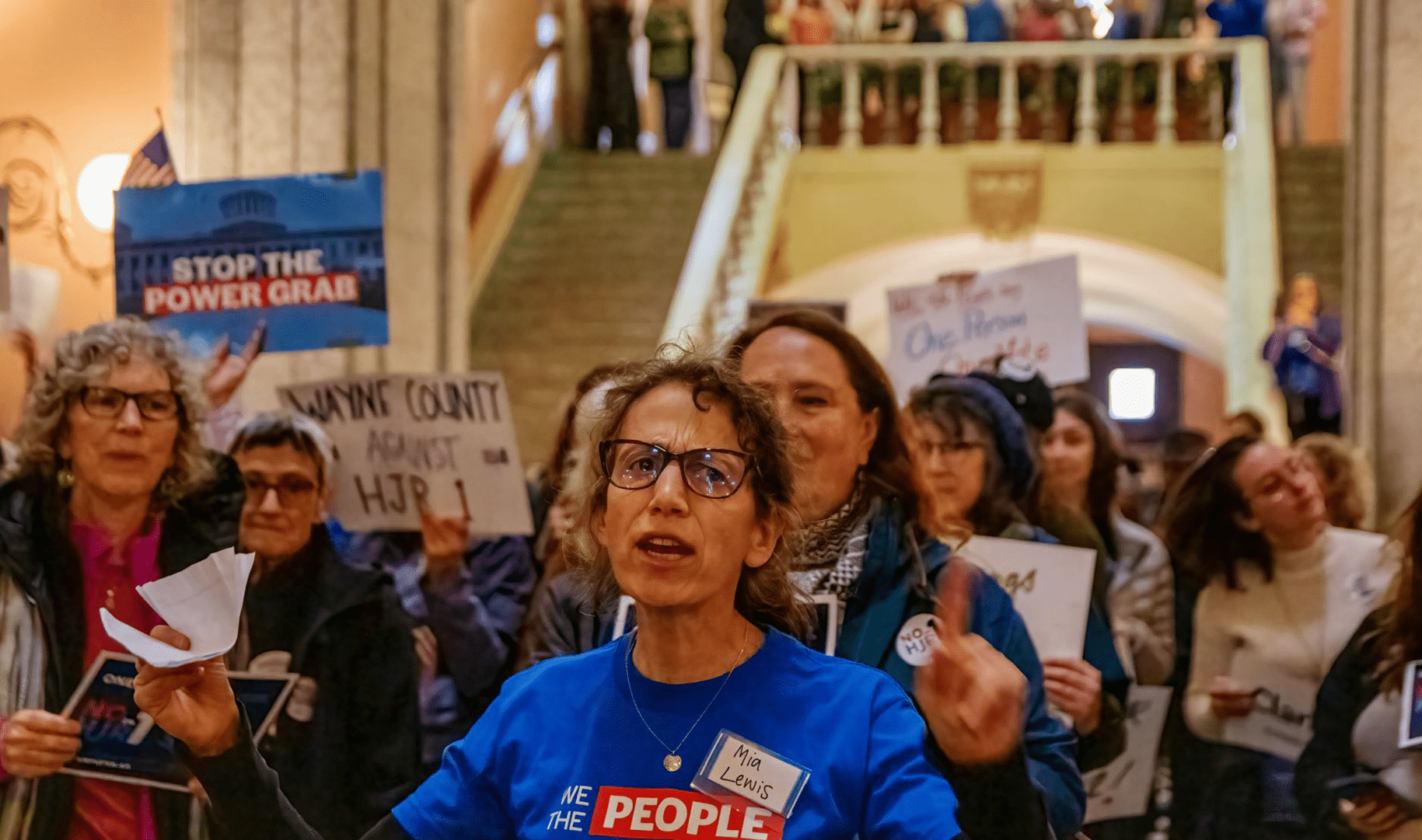

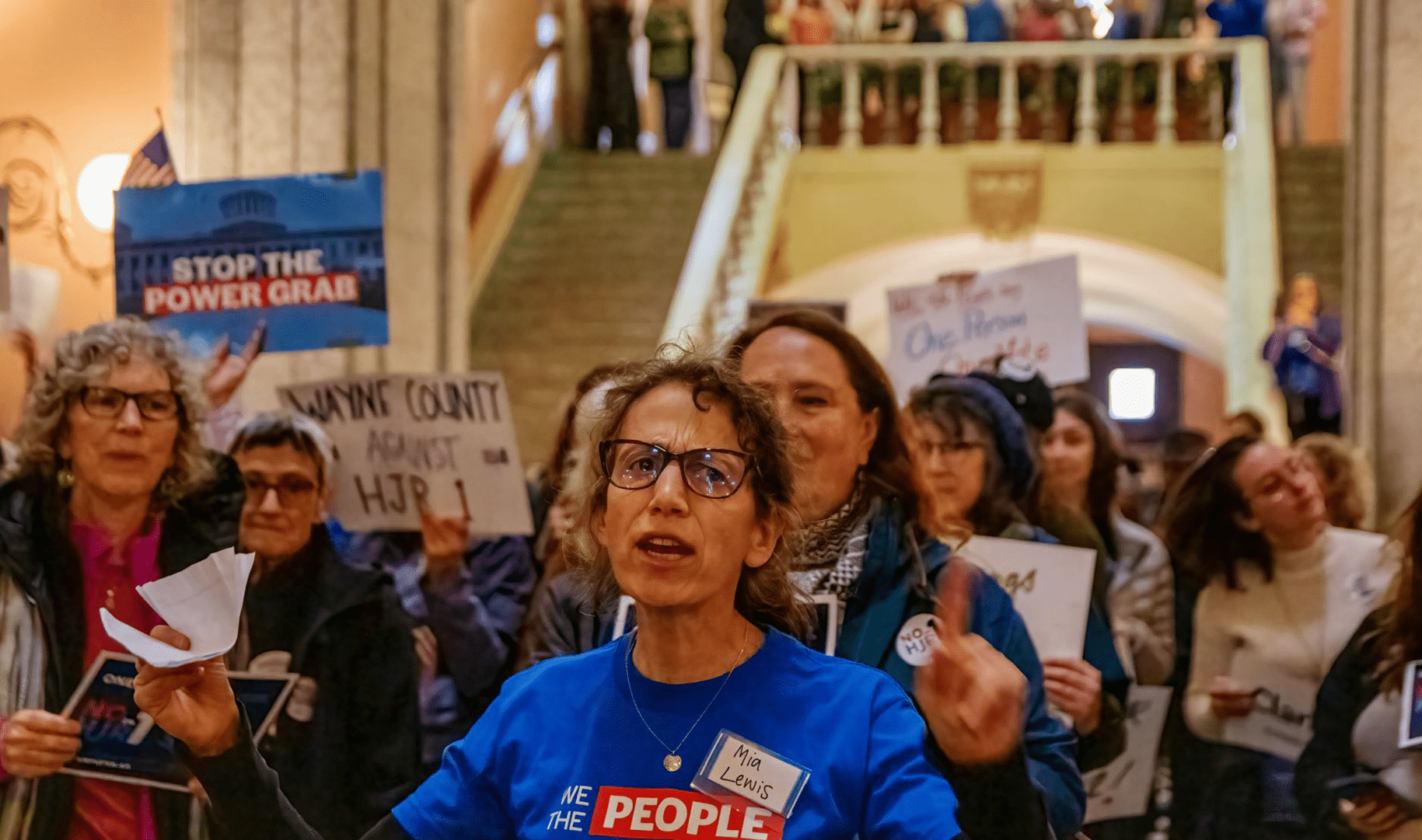

The stakes are clear in: Michigan

The recent revelation by the Detroit News that Trump personally pressured members of the Wayne County (Detroit) Board of Canvassers in 2020 was no surprise given what was already known of his actions that year. But it was a reminder of the critical role these local bodies play in Michigan: Boards of canvassers are divided equally between parties, which leaves Democrats particularly vulnerable to shenanigans in a populous stronghold like Wayne.

Since 2020, the Michigan GOP has replaced their local election officials with people who have defended subverting elections. Republicans on the statewide board of canvassers have also shown they’re willing to go along with such maneuvers. Still, Michigan has new legal standards clarifying that canvassers lack the discretion to reject valid results; in 2022, Democrats defended their majority on the state supreme court, the body that would be called on to enforce such standards.

Also keep an eye on: Election deniers lost most of their bids to take power in swing states in 2022, but there are plenty of other spots to watch. Officials with a history of delaying election certification won reelection last year in Pennsylvania, though Democrats solidified their hold on the state’s supreme court. Trump allies will run local election offices in swing states such as Arizona and Georgia, heightening the potential for havoc. And a fake Trump elector from 2020 has a seat on the Wisconsin Election Commission, the body that runs elections in a key battleground state.

6. How easy will it be for voters to vote by mail?

If you want to vote by mail in this year’s elections, will you need to provide an excuse to get an absentee ballot? Will you have easy access to a drop box to drop off your ballot? What are the odds your mail ballot gets tossed on a technicality? That all depends on your state, the bills your lawmakers are crafting, and may even hinge on the decisions of your local government.

The stakes are clear in: Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has one of the nation’s most decentralized systems when it comes to mail voting procedures. As Bolts reported this fall, county officials there have a startling amount of discretion on how to deal with deficient ballots, whether to install drop boxes, and even whether to have armed law enforcement guarding them. Democratic wins in November’s local elections are likely to preserve the status quo in the most populous counties. But democracy advocates are pushing for better procedures on how voters can fix mistakes, and more robust requirements for drop boxes; they’ll be waging this battle both statewide and county by county throughout 2024.

Also keep an eye on: Since the 2020 presidential race saw an explosion of mail voting during the pandemic, many states have revised their rules—some to make it harder, others to expand its availability. The 2024 cycle will be the biggest test yet for how these laws impact turnout. For instance, Democrats in Michigan this year passed new laws that make it easier to vote by mail and set new requirements for drop boxes. Inversely, Georgia Republicans’ restrictions on mail voting, adopted in 2021, just survived their latest court challenge in October. In Mississippi, a new state law that criminalizes helping people with absentee voting is currently blocked by a federal court ruling. Meanwhile in Wisconsin, Democrats are hoping that their new majority on the state supreme court enables voters to use ballot drop boxes, a practice the state disallowed in 2022.

7. Will more states ease voter registration?

By requiring citizens to register to vote, states have erected a barrier between voters and the act of voting. But some have pushed boundaries in recent years, finding ways of shifting the burden of registration onto the state or eliminating unnecessary deadlines or paperwork, with some proposals questioning whether we need registration at all. This will be another critical year to watch how states ease or curtail access to this fundamental right.

The stakes are clear in: New Jersey

Almost half of states allow voters to register on the day of an election—a major convenience for any of the countless people in those states who may otherwise have missed a deadline. Liberal as it is, New Jersey is not among the states with this option, mainly because of opposition from its Democratic state Senate president. The state is weighing the policy afresh this year.

Also keep an eye on: Oregon and Colorado have been badgering the Biden administration for years to allow states to automatically register people to vote when they sign-up for Medicaid; if the feds acted on this, hundreds of thousands of people would be registered to vote. Other states are considering new laws that would set up or expand automatic voter registration, including applying it to new state agencies, including Ohio, where organizers are pushing for a November initiative; and California, where proposed legislation would likely end up with more people on voter rolls; as well as Maryland and New Jersey, where progressives hope to copy Michigan’s recent first-in-the-nation move to automatically register people to vote as they exit prison.

8. How will states keep changing felony disenfranchisement laws?

Each state sets its own laws governing whether—and to what extent—people with previous felony convictions lose voting rights, and the national landscape on this front is ever-changing; 2023 alone saw landmark voting rights restoration in New Mexico and Minnesota, plus dramatic rollbacks in Virginia and Tennessee. The United States has long stood out among democracies worldwide for how aggressively it denies voting rights to people with criminal records, and that won’t change in 2024: an estimated 4 million citizens will be blocked from the ballot, but upcoming legal cases and political decisions could affect that number.

The stakes are clear in: Mississippi

A panel of judges on the federal Fifth Circuit appeals court issued a shock decision last summer that struck down Mississippi’s extraordinarily harsh disenfranchisement rules, which strip hundreds of thousands of people of their voting rights for life. (An estimated 11 percent of the state’s adult population can’t vote, currently a national record.) But when the state appealed that panel ruling, the full Fifth Circuit agreed to reconsider it, voiding the prior decision and setting up a major legal showdown this year. If plaintiffs win again, it would bring about one of the most significant expansions of the franchise in a given state in recent history. But don’t bank on that, as voting rights advocates have been bracing for defeat.

The stakes are also clear in: Virginia

Virginia Democrats have been sharply critical of Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin’s 2023 decision to reverse his predecessors’ policy of automatically restoring people’s voting rights. Having just seized control of the legislature, they say they’ll now look to bypass Youngkin by referring to voters a constitutional amendment to remove rights restoration power from the governor’s office. That process would take multiple years to reach the ballot, though.

Also keep an eye on: Progressives in California, Massachusetts, and Oregon hope to go further and altogether eliminate felony disenfranchisement this session, enabling anyone to vote from prison. (This is already law in Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, D.C.). Inversely, Tennessee stepped up restrictions on rights restoration in 2023, and now requires people to pay new application fees; 2024 will be the new system’s first major test.

9. Will sheriffs, prosecutors and other law enforcement officials step up policing and intimidation around elections?

Trump’s lies about the 2020 election inspired right-wing officials across the country to launch special law enforcement units to root out and punish election crimes. They also fueled crackdowns in states where GOP officials had spread the myth of widespread voter fraud long before Trump, leading to a raft of laws creating new election-related crimes or increasing existing penalties around voting. Some GOP law enforcement officials have partnered with far-right election denier groups that are ramping up their own efforts to police voting ahead of Trump’s attempt at re-election.

The stakes are clear in: Texas

Bolts reported last year that the elected sheriff and DA in Texas’ Tarrant County, home to Fort Worth, were launching a new law enforcement task force to investigate and prosecute voter fraud. Phil Sorrells, the DA, ran with Trump’s endorsement in 2022 and won on promises to ratchet up policing of elections. The sheriff, Bill Waybourn, has become a right-wing celebrity for his fealty to Trump while also facing mounting criticism at home for a spike in deaths and other scandals at the county jail he oversees.

Political pressure over baseless claims of fraud have already disrupted the running of elections in Fort Worth; Tarrant County’s widely respected elections chief stepped down last year after months of harassment from election deniers, which included racist attacks about his heritage. And election deniers have claimed without evidence that Waybourn’s close reelection win in 2020 suggests there was fraud. (Waybourn is up for reelection again this year.) That all sets the stage for even more allegations and investigations in a county with a long history of harsh and questionable prosecutions for voter fraud during a critical election year.

Also keep an eye on: Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in 2022 established the country’s first statewide agency dedicated solely to investigating election crimes, which quickly resulted in a series of arrests of people with prior felony convictions accused of voting illegally—many of whom have said the government had told them they could vote and whose prosecutions have since fizzled. Bolts has also reported how sheriffs in the swing states of Arizona and Wisconsin have bolstered election conspiracies and partnered with leading purveyors of election conspiracies to increase policing of elections.

10. Where, and how, will the assault on direct democracy continue?

Many Republican-run states have curtailed the ballot initiative process in recent years, looking to limit citizens’ ability to put new issues on the ballot. After the GOP failed to derail an abortion rights initiative in Ohio in August, Bolts hosted a roundtable with democracy organizers who all said they expected the assault on direct democracy to continue unabated in 2024, fueled by conservative efforts to protect abortion bans and fight off redistricting reforms.

The stakes are clear in: Missouri

Reproductive rights advocates have turned to the only tool at their disposal in red states: directly asking voters to protect abortion rights. In Missouri, organizers have already had to fight off their attorney general’s effort to sabotage such a measure. In 2024, they’ll also have to contend with GOP proposals to change the rules and make it harder for voters to approve initiatives. One bill, filed by a GOP lawmaker for the 2024 session, would create a new requirement for initiatives to receive a majority in half of the state’s congressional districts in order to pass. Because the state’s map is gerrymandered to favor Republicans, this would force a progressive ballot initiative to carry at least one district that’s far more conservative than the state at large—a tall order for the abortion rights measure to meet.

Also keep an eye on: Republicans are eying changes to state law in other states like Oklahoma to block abortion rights measures. In Arkansas, where the GOP passed a law last year that made it much more difficult to get a measure on the ballot, the coming year will test what space the law has left for organizing efforts. And democracy advocates in Idaho and Ohio expect Republicans to look for new maneuvers to restrict the initiative process.

11. What will happen to DAs and judges targeted for removal in southern states?

Conservative officials in southern states have in recent years created, expanded, or ratcheted up the use of state powers to oust local DAs who make policies they disagree with—such as declining certain low-level charges or ruling out abortion prosecution. They have also targeted high-court judges over their decisions and statements.

States to watch: Georgia and Texas

Republican anger toward local prosecutors reached a fever pitch in Georgia last year with Fulton County DA Fani Willis’ decision to investigate and ultimately prosecute Trump for his efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election. As Bolts reported, Georgia Republicans established a new board with authority to oust DAs over their charging decisions, though the law has so far been tied up in court. Similarly, after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision triggered a near total criminal abortion ban in Texas, GOP lawmakers there pushed through legislation expanding powers to oust local DAs who said they would refuse to prosecute abortion and other cases, a law that may be turned against some local officials this year.

Also keep an eye on: Florida, where the governor has broad power to remove and replace local elected officials, DeSantis has ousted two local prosecutors over the past two years, and voters will get to weigh in on who should occupy those offices for the first time since. Residents of St. Louis will also vote for the first time since the removal of their elected prosecutor by the Republicans in the Missouri state government. And Tennessee Republicans have stepped up efforts to sideline Memphis’ new Democratic DA. There are similar efforts to target judges, like the only Black woman justice on North Carolina’s supreme court, for removal.

12. How will localities innovate to boost participation in democracy and local elections?

Even as some places tried to make voting more difficult, 2023 also saw many states and cities experiment with new strategies to expand the franchise and encourage more participation in democracy. This year’s elections will see some of the first fruits of those efforts, as well as other places possibly following suit.

The stakes are clear in: Municipalities experimenting with noncitizen voting

Boston’s city council in December passed an ordinance to allow noncitizens with legal status to vote in local elections, a landmark win for progressives who’ve championed this issue locally for years, as Bolts reported in 2022. But the Massachusetts legislature would need to authorize Boston’s reform, which may come to a head this year. Boston’s move comes as other cities have adopted noncitizen voting. Last year, Burlington became the latest Vermont locality to allow noncitizen voting in local elections, giving more members of the state’s growing immigrant communities a say in things like school boards and municipal budgets. Washington, D.C. passed a similar ordinance last year, though a lawsuit was filed last year challenging the measure, a battle likely to continue into this year.

Also keep an eye on: Other innovations to increase participation are set to take effect this year, and will face their first tests. Michigan allowed 16 and 17-year-olds to pre-register to vote before their 18th birthday, while New York passed a law requiring high schools to distribute registration and pre-registration forms to students. Colorado and Nevada recently expanded voting access on Tribal lands. New York also just moved some local elections to even years to boost turnout, a reform that may inspire proposals in other states on an issue that is gaining steam around the nation.

Correction: The article has been corrected to reflect where Trump appealed his disqualification from the Maine ballot.

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.